SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 21 (2013) pp.18-39.

Title: Returning Fathers. Sagas, Novels, and the Uncanny

Author: Torfi H. Tulinius

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Statement of responsibility:

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Journal

Source(s):

Tulinius, Torfi H. 2012-2013.

Returning Fathers. Sagas, Novels, and the Uncanny.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 21: 18-39.

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- fathers

- sagas

- fiction

- Grettir’s Saga

- MDH: started markup 4th September 2013

- MDH: entered author's proofing corrections 11th March 2014

- MDH: added footnote 18th May 2014

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 23rd May 2014

- MDH: corrected American spelling to Canadian 26th February 2019

Returning Fathers. Sagas, Novels, and the Uncanny

Torfi H. Tulinius

ABSTRACT: This article addresses the question of the relationship between the sagas

about early Icelanders (Íslendingasögur) and the European novel tradition. Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope is used to

describe the world of these sagas which is characterized by uncertainty of identities.

Todorov’s concepts of “étrange,” “merveilleux” and “fantastique” are adapted to the

analysis of several sagas. The figure of the dead father is identified

as a key theme, which leads to an interpretation of Grettir’s Saga based on Lacan’s theory of the Unconscious structured as language.

RÉSUMÉ: Cet article tente de comprendre les sagas des Islandais (Íslendingasögur) dans le contexte de l’histoire du roman en Europe. Le concept bakthinien du chronotope

permet de décrire le monde de ces sagas comme caractérisé par l’indétermination des

identités. Les catégories « étrange », « merveilleux » et « fantastique » formulées

par Todorov sont adaptées pour éclairer plusieurs sagas. La figure du père

mort y est identifié comme thème central, ce qui mènera à une interprétation de la

Saga de Grettir basée sur la théorie lacanienne de l’Inconscient structuré comme un langage.

Is it legitimate to view the sagas about early Icelanders, or Íslendingasögur, as an early manifestation of the European novel? In his influential study of Hrafnkelʼs Saga, Sigurður Nordal gave a positive answer to this question. Nordal’s intention was

first and foremost to undermine the widespread belief among his contemporaries in

the historical veracity of the sagas. He was also insisting on the creativity and

artfulness of the individual responsible for this particular saga and, implicitly,

the authors of all of the forty or so texts which compose the genre of the Íslendingasögur (Nordal 70). Since Nordal’s days, scholars have explored the sagas from other perspectives:

anthropological,

legal, religious, etc., also coming back occasionally to their literary aspects. However,

few have addressed the question of their relationship with the novel tradition. There

are two notable exceptions to this: Joseph Harris, who published an important article

on the “Saga as Historical Novel” (187–219), and Vésteinn Ólason, who devoted a short

but useful chapter to it in his Dialogues with the Viking Age (228–37).

For Harris the sagas are “historical” because their authors’ vision of the past was

shaped by a Christian attitude to time:

from Creation to Fall and from Incarnation to the Day of Judgement. The Conversion

of Scandinavia, and more specifically Iceland, is a watershed in their construction

of the past. It is to a large extent based on an opposition between pagans and Christians,

where the different people from the past are characterised in relation to Christian

values, for example “noble heathens” such as Njál or apostates such as Earl Hákon.

The sagas are comparable to Sir Walter

Scott’s historically inspired novels, because they blend together real and fictional

events and characters, but also because they are to some extent meditating on a past

which is both different from and similar to the present (Harris 230; 260).

Though Vésteinn Ólason admits there is some basis for the comparison between the sagas

about early Icelanders and the novel, he chooses to highlight their differences (235).

Among these are the saga authors’ apparent lack of interest in the characters’ inner

life and the absence of authorial commentary and of a clear distinction between society

and individual, which is an important aspect of the novel as genre. Ólason even undermines

any attempt to draw a parallel between the terse style of the sagas and the seemingly

objective narrator of Hemingway (235–36). His conclusion is that the sagas are “a

distinctive and, in certain respects, unique literary genre. For all the features

they share with other categories of narrative there are a number of important differences

relating ultimately to the special historical and cultural circumstances out of which

the Íslendingasögur grew” (237).

It is of course impossible to disagree that these sagas are the fruit of “special

historical and cultural circumstances.” This is true of every artistic form. However,

one of these circumstances is not,

as might be thought, that Iceland and the other Nordic countries were isolated from

the rest of Western Europe in the thirteenth century. Quite to the contrary, they

were very much a part of medieval Christianity, not only through religious beliefs

and ecclesiastical practices, but also in the general trends structuring society,

such as the strengthening of royal power and the development of a written lay culture

(Winroth 164). Studying the sagas with an eye on the more recent novel is therefore

a contribution

to the history of a form of expression which emerged in the medieval West, but has

spread to the rest of the world and remains quite vibrant today (Scarpetta).

There is no consensus on when to date the beginnings of the novel as such. Many look

to the realist novels of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England and France (Watt).

Others want to push it back further, at least as far as Cervantes or Rabelais (Kundera).

Still others see its origins in Late Antiquity and argue that too little has been

made of the influence of novels from that period on late medieval authors (Doody).

Finally, there are those who maintain that the main characteristics of the novel

were already in place in the twelfth century in the works of Chrétien de Troyes (Zink

38).

There is also a debate on how to define the novel, turning not least on whether or

not romance and fantasy belong to the genre or whether narratives that do not show

some degree of realism should be excluded (McKeon; Doody). It is worthwhile to consider

the sagas about early Icelanders in this context, because

in many respects they can be viewed as realist literature, while in others they portray

characters and events which do not fit into a modern view of what can actually happen

in reality. On the one hand, the physical properties and the social constraints of

the imaginary world of the Íslendingasögur are quite similar, despite some differences, to what we know about the times in which

they were written. On the other, things happen in the sagas that modern readers would

qualify as fantastic or supernatural.

In the following pages, this quality of the world of the sagas about early Icelanders

will be discussed in light of two separate approaches to the novel. In an earlier

and briefer section, I will explore to what extent the concept of the chronotope, as formulated by the Russian theorist of the novel, Mikhaïl Bakhtin, is useful to

explain the particular features which distinguish these sagas from other Old Norse

literary genres. Special attention will be given to a type of “in-betweenness” or

“uncertainty of identities” which characterises this particular group of sagas. In

a later and longer section,

more attention will be given to the supernatural in these sagas. Here I will take

my cue from Francis Dubost and his work on the “fantastique médiéval” to suggest possible

novelistic readings of passages from three sagas, Egil’s Saga, Eyrbyggja Saga, and Grettir’s Saga.

Chronotope and Ambiguity

We know enough about the early development of narrative literature in twelfth- and

thirteenth-century Iceland to see how an image of the period of Settlement and Conversion

was progressively constructed before the advent of the sagas about early Icelanders

(Kristjánsson 21-24). In the twelfth century, the works of Ari the Learned established

a chronology of

the discovery, settlement and conversion of the country, as well as the founding of

its major institutions (Alþingi, Fifth court, bishoprics of Skálholt and Hólar). At

the same time, individual traditions about the names and provenance of settlers were

collected for the earliest and lost version of Landnámabók (Kristjánsson 126). Understandably for a Christian nation, the period of the Conversion

was very much

in focus (Mundal). The mental image of this period was further enriched a few decades

later with the

development of biographies of the Norwegian rulers, especially those who ruled during

the Conversion period. Often included in these sagas, were short accounts about Icelanders,

many of them skalds, and their dealings with these rulers (Jakobsson 395). It was

only a question of time before somebody would have the idea of shifting the

centre of the story from the king to the subject, joining together the world of Norway

in the Conversion period and that of Iceland.

These texts developed a constructed image of the past, a “fictional world,” which

characterizes all of the sagas about early Icelanders and constitutes them

as a genre (Auden; Pavel). Mikhaïl Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope can be used

to clarify this. The chronotope

is a configuration of space and time which is specific to each literary genre and

has a certain number of properties (Bakhtin 84). The chronotope of the French chansons de geste, for example, is similar to that of the sagas about early Icelanders in the fact

that it is based on the mental construction of a historical period two to three centuries

older. It differs from the chronotope of the sagas however, because the latter are

more embedded in reality, both natural—heroes of the sagas about early Icelanders

do not slice their enemies’ hauberks with one blow of their swords—and social—the

saga heroes are more involved in complex social relations than a Roland or a Guillaume

d’Orange.

The time and settings of the sagas about early Icelanders are Iceland and countries

to which Icelanders were likely to travel in the period from the ninth to the eleventh

century, i.e. from the Settlement to the Conversion. These times and places constitute

their specific chronotope which has a certain number of properties. One of them is

that the social and physical world of these sagas is more or less identical to that

of their original authors and audience. This probably has quite a lot to do with the

fact that these sagas present themselves as history, even though their historical

truth is disputable (Kristjánsson 204-06). They nevertheless have a feature which

distinguishes them from the other saga genres,

most notably from the sagas of the Sturlunga compilation, which are accounts of events

of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, i.e. contemporary to the time of writing.

Elsewhere, I have called this characteristic of the chronotope of the Íslendingasögur “ontological uncertainty” (2000a 253). By this I mean an inherent ambiguity attached

to the characters and events of these

sagas. This ambiguity is closely linked to the fact that the sagas about early Icelanders

take place in a transitional period between paganism and Christianity. The characters

are neither entirely pagan nor completely Christian and this has an impact on how

they are construed by the saga authors and their audience. Their moral ambiguity can

be explored more openly than if they were contemporary Christians.

But the chronotope of the Íslendingasögur is also foundational. Iceland is being settled and the basic social and power relations

within it are being established. The settlers had a certain position within the society

they came from. They did not necessarily retain that position when they came to Iceland.

Indeed, settling in a new country creates basic uncertainty about social status, which

is another aspect of the ambiguity in the sagas about early Icelanders and their chronotope.

This can surely be related to a feature of thirteenth-century society in Iceland.

The changes happening in the first half of the century, at the same time as the first

Íslendingasögur were being written, made it quite likely that a sort of a “déclassé” middle class

would appear in society. In this period, there must have been quite

a number of people who were the descendants of chieftains and understood themselves

to be such, but who were not really members of the ruling class. Their possibilities

of social promotion were through service to those with more power than themselves.

The Saga of Hallfred gives us an example: Hallfred was the son of Ottar, a noble Norwegian who had to

emigrate to Iceland after his father was killed. By the time Ottar arrived in Iceland,

all the best land had been settled, and he had to satisfy himself with acquiring land

in an area controlled by the powerful chieftains of Vatnsdalr. When he attempted to

position himself as their equal, he was forced to leave the region (Hallfreðar saga 143-44). His son, Hallfred, tried to assert dominance over someone he considers as

his inferior,

but failed and was made aware of his dominated position within society. The only way

for him to acquire the social position that he feels he is entitled to is through

royal service. It is possible to identify persons in the contemporary sagas who could

be seen as occupying analogous positions within society as those of Ottar and Hallfred:

men who claimed high origin but were nevertheless powerless and were caught up in

a conflict between serving more powerful patrons or trying to compete with them. Many

of these looked to the royal court as a means to social promotion (Tulinius 2000b

201-05).

Uncertain identities of both the social and metaphysical kind are quite at the heart

of the saga of another poet, Egil Skallagrimsson. The identity of the sons of Hildirid,

whether they are bastards or legitimate heirs, is the basic uncertainty at the root

of Thorolf Kveldulfsson’s undoing, they affirming their legitimacy, he denying it.

Later in the saga, the denial of the legitimacy of Asgerd, Egil’s wife, is the source

of the main conflict between Egil and King Eirik blood-axe, who denies what Egil affirms.

In both cases, doubt is being cast on social identity.

A similar observation could be made about religious and moral identity. Egil is prime-signed,

i.e. not quite a Christian and not quite a pagan. The author plays continuously and

consistently throughout the saga on this ambiguity, among other things in his wedding

to Asgerd, his brother’s widow, something a pagan is allowed to do and not a Christian

(Tulinius forthcoming).

But there is another side to this play with ambiguous identity that so characterizes

the saga of Egil: identity is also always being affirmed. The saga as a whole can

be read as establishing the social identity of the descendants of Skallagrim. The

equals of Norwegian aristocrats, they have left the country because they haven’t been

able to submit to the new authority of the king. In Iceland, they themselves claim

authority over the region of Borgarfjörður, defending this claim when it is challenged

by Steinar in the last part of the saga.

Similarly, Egil’s religious identity is finally established at the end of the saga,

after its ambiguities have been played out. Indeed, the whole point of the story of

Egil’s bones being found under the altar of the church at Mosfell and buried again

on the edge of the cemetery, is to establish his correct theological status. He is

not a pagan. That is why his bones are taken from the burial mound he is first laid

to rest in, and moved to a Christian cemetery when the country is converted. However,

he is not quite a Christian, and certainly not a saint, as saints are the only people

entitled to being buried under the altar. His correct place is at the edge of the

cemetery where babies are buried who have only received the shorter baptism because

they died before a priest could baptize them properly. This is prescribed in the law-book

Grágás. Incidentally, the term prímsigning is used in Grágás for the shorter baptism (Tulinius 1997).

Egils Saga is therefore characterized by a dialectical relationship between establishing identity

and playing with its ambiguities. This is allowed by the nature of the chronotope

of the sagas about early Icelanders. The social instability of the Settlement period

makes it possible to explore the uncertainties of social identity whereas the “in-between-ness”

of the Conversion period permits play with moral and religious ambiguity. This tension

between creating identity and deconstructing it is to my mind one of the principal

characteristics of the genre.

Uncertainty and the Fantastic

Another property of the chronotope of the sagas about early Icelanders by which it

also has a special relationship to uncertain identities is their portrayal of the

supernatural. As has already been said, despite their perceived realism, the sagas

present characters and events that do not fit into modern views of reality. This seems

to be a problem, unless we relate it to another stream in the history of the novel

which runs parallel to the realist stream, namely the fantastic, which yields a literature

in the nineteenth century that Tzvetan Todorov studied in his influential 1975 book

on the subject. This literature is quite different from the realist canon though its

roots reach far back in literary history (Doody). Its vogue, especially in the nineteenth

century, has to do with a crisis of realist

representation that prefigures many of the intellectual developments of the twentieth

century. This crisis can be seen in the works of major authors such as Flaubert, Dostoyevsky

and Maupassant (Jackson; Bayard).

Todorov distinguishes between what he calls “merveilleux” and “étrange.” If the reader

decides that the world he has been reading about is governed by other

rules than the natural world, if for example birds can talk and men can become wolves,

he is in the “merveilleux.” We could also call it the world of fantasy. When on the

other hand the reader comes

to the conclusion that the laws of nature need not be changed and there is an explanation

for the strange phenomena observed, even though it is not obvious, we are in the “étrange.”

In this literature, there is hesitation but it is dispelled at the end. There is

a third possibility, which is when this hesitation is maintained and the reader continues

to be bewildered by the occurrences described after he has finished reading the story.

In Todorov’s view, this is “littérature fantastique” (41).

It is this hesitation which is interesting to relate to the “uncertain identities”

of the chronotope of the sagas about early Icelanders and at least some examples

of the way paranormal events are presented in them. Todorov’s concepts derived from

his analysis of nineteenth-century literature have already been adapted to medieval

literature by the French literary specialist, Francis Dubost in his 1991 study Aspects fantastiques de la littérature narrative médiévale (XIIème et XIIIème siècles) (220–42). I will now take my cue from him and attempt a reading of one of the most

genuinely

hair-raising episodes in the saga literature: Grettir’s fight with the revenant Glám.

This fight and the events leading up to it—chapters 32 through 35—are in many ways

exceptional in the saga. To begin with it serves as a break in the story of Grettir’s

life: the narrative leaves him for two chapters for the first time since he entered

the saga, in order to present the characters and set the stage. Secondly, though it

is far from Grettir’s only clash with the supernatural, it is the one which receives

the most elaborate treatment. Thirdly, this elaboration has a twofold effect, on the

one hand it creates uncertainty and raises questions about Glám’s status, both before

and after his death and haunting of the valley, and on the other it progressively

shifts from being the collective experience of a community to the private experience

of the individual, Grettir. This brings us to the fourth aspect of this episode which

gives it special importance within the saga: Glám lays a curse upon Grettir which

will be the cause of all his subsequent misfortunes. This curse is the explicit answer

to the question that underlies the whole of the saga: why did a man who had all it

takes to be a hero make such a mess of his life, ending it as an outlaw? In other

words an interest is taken in a person’s experience as an individual.

There are three aspects which make this episode especially relevant to the question

of the saga’s relationship to the novel: 1. the elaborate way in which the narrative

outlines Glám’s supernatural status; 2. the progressive individuation of the point

of view on the supernatural; 3. how this experience of the supernatural is closely

linked to the problematic status of this individual, which is what the saga is about.

Before discussing each of these aspects, a brief summary of the four chapters is necessary

(Grettis Saga 107-23). Thorhall, a farmer from the North of Iceland, has a problem. Supernatural

beings haunt his valley and make his herdsmen’s life miserable so they won’t stay

in his service. One summer he goes to Parliament for advice. He is told to hire Glám,

a Swede who has recently arrived in Iceland, an unlikable fellow but one who won’t

mind dealing with such creatures. Thorhall meets Glám and they agree that he will

start working for him when winter begins. Everything goes well until Christmas Eve,

when Glám refuses to fast like the other members of this Christian household. He goes

out to take care of his flock but doesn’t come back. The next day he is found dead

amidst the traces of a terrible battle. Huge bloody tracks lead into a boulder and

it is believed that the supernatural beings which have haunted the valley until then

have also perished in the fight with Glám. For mysterious reasons, Glám’s body can’t

be moved to a cemetery and is simply covered with stones. Now it’s his turn to haunt

the valley, but in a much more virulent way, attacking the farms. No one can do anything

to stop him and all of Thorhall’s people leave, his daughter is driven insane, and

he remains alone with his wife, while Glám’s ghost goes on the rampage every night,

turning the once prosperous valley into a desert.

Now the story returns to Grettir, who is looking for a heroic deed to accomplish.

He hears of the events and decides to go despite warnings that it can only bring him

misfortune. The first night he is there, nothing happens, the second nothing seems

to happen either, until Thorhall and Grettir discover that Grettir’s horse’s back

has been broken. The third night Glám arrives. He is huge and truly monstrous and

Grettir and he fight in the night, first inside the house until they are carried outside

where Glám falls on his back with Grettir on top. The wind blows a cloud away from

the moon and Glám’s face is illuminated, Grettir stares into his eyes and is paralyzed

by what he sees. Glám then lays a curse on Grettir, saying that he will not become

any stronger than he is now, even though he has only attained half the strength he

was supposed to, also that from that moment on all his deeds will turn out badly for

him and finally that Glám’s eyes will haunt him for the rest of his life making him

unable to stay alone at night. After this, Grettir regains his strength and cuts the

ghost’s head off, placing it by its buttocks before burning the cadaver and burying

its ashes where nobody ever passes.

If we begin by looking at Glám’s status as a supernatural being, what principally

characterizes the part of the episode until Grettir becomes involved is that the narrator

delays being explicit about Glám’s nature. Instead he uses a technique that involves

giving clues as to what Glám is. These clues are inconclusive and sometimes contradictory

and therefore entertain uncertainty about his status as a being.

The first sign that something is out of the ordinary is the disquiet Glám inspires

in people. Even the sheep herd together when they hear Glám’s deep voice (Grettis Saga 110). Indeed, this last element indicates some kind of common features with the wolf,

a similarity also suggested by his description: gray eyes set wide apart and wolfish

gray hair. Though he is awe-inspiring and unpleasant, there is nothing in his description

until then that prepares us for what is to come. Despite his refusal to embrace Christianity

and take part in religious activities, he does not seem evil. He rather appears to

be a survival from the pagan period, still only a decade or so away at this time in

the saga: half man, half wolf. His refusal to comply with Christian rules such as

fasting on Christmas Eve does not necessarily mean that he is an enemy of Christianity:

he is outside religion.

There are other signs however that seem to indicate that Glám is not just a being

from the pre-Christian world and that what happens must be understood in the context

of a Christian dialectic between Holy and Unholy. Glám is being moved to a cemetery

and the supernatural heaviness can therefore be interpreted as an intervention from

some force which does not want Glám’s body to be laid to rest in hallowed ground where

it can do no harm (Grettis Saga 112-13). This interpretation is rendered more plausible by the fact that the body

cannot

be found when the priest accompanies the men who are to move it. The fact that one

of the attributes of the devil in medieval times was the ability to make people see

what was not there and not see what was there makes this interesting (Pálsson 99).

Until the very end of the episode, there is constant indecision concerning Glám’s

status. Some signs suggest that he is a pagan survival in this transitional period,

others that he is diabolical. Hermann Pálsson has drawn attention to the close parallels

between the Glám episode and the account, in the bishop’s saga Guðmundar saga, of the ghost Selkolla. Here an unbaptized baby dies out in the open, is invested

by an evil spirit, and becomes such a terrible monster that only the holy Gudmund

can lay it to rest. As Pálsson points out, Glám’s status in Christian terms is the

same as that of the baby, neither has been baptized and neither is protected against

possession by demons (7).

Through the different stages of the narration it would thus have dawned upon the medieval

audience of the saga that Glám’s status is that of a non-baptised being, marginally

supernatural, which has been possessed, after its death, by an evil spirit. This evil

spirit is not the local ghost who haunted the valley before Glám’s arrival, but one

who is capable of having a far-ranging effect on an individual’s life. It seems reasonable

to connect him to the boy who makes Grettir lose his temper later on in the saga,

when he is submitting himself to the ordeal that would have proven his innocence in

the crime he is accused of. The boy, the saga says, was thought to be an evil spirit

sent for Grettir’s misfortune (Grettis Saga 133). What is being suggested is that some kind of invisible force is conspiring

against Grettir’s soul.

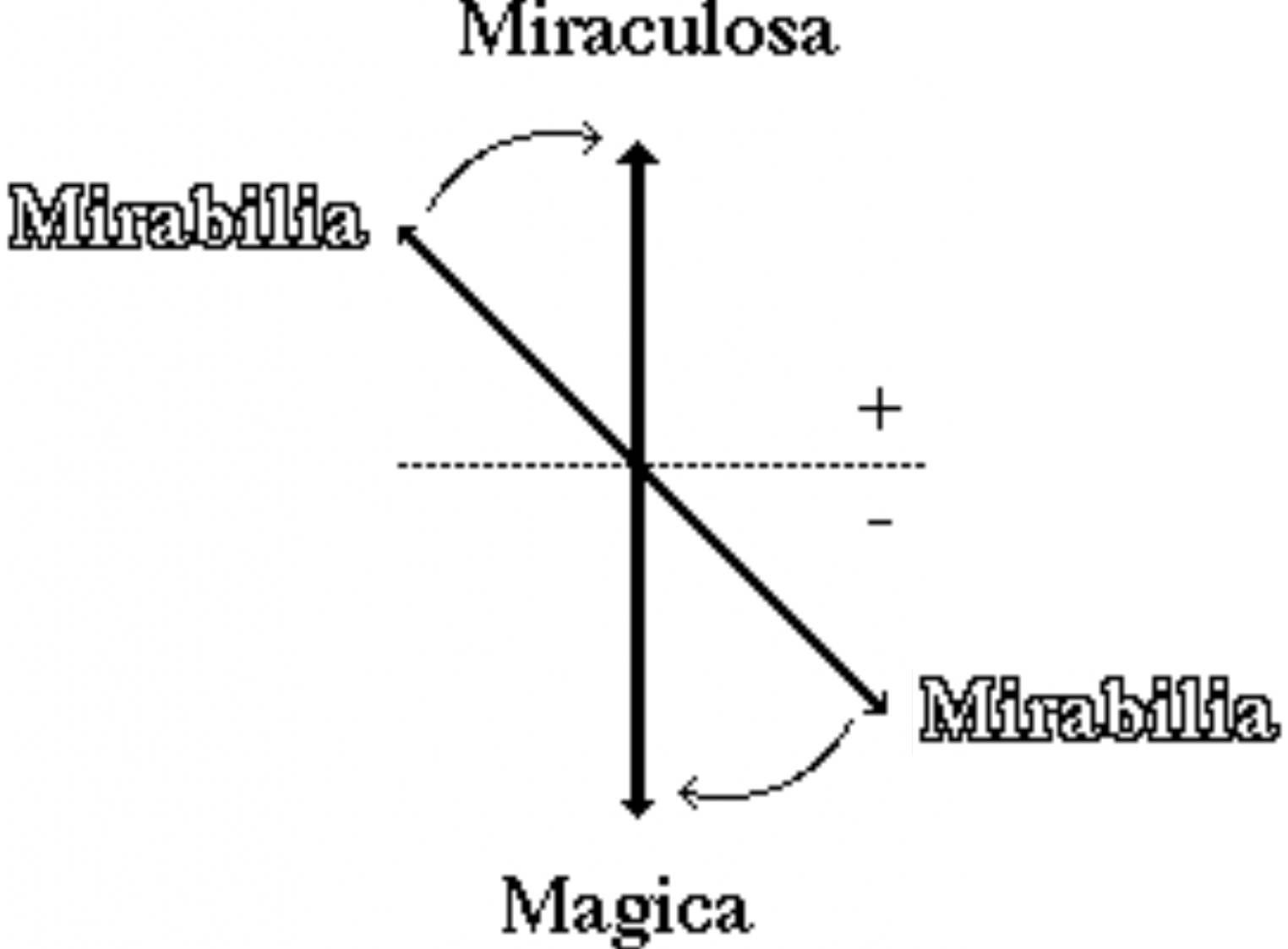

Miracles, magic and marvelous

How are we to understand this dialectic between paganism, the diabolical and Christianity?

I believe it can be useful to take a look at what was happening concerning attitudes

to the supernatural during this period. In his book on L’Imaginaire médiéval, Jacques Le Goff discusses the attitude to the supernatural of twelfth- and thirteenth-century

clerics for whom there are three types of supernatural phenomena: “miraculosa,” i.e.

miraculous events or deeds inspired by God or his chosen ones, “magica,” engines of

the Devil or his followers, and finally “mirabilia,” unexplained wonders, mostly from

pagan times, which came more to the attention of

clerics in these centuries as compared to earlier times (17). If we try to place

Glám within this framework, he would be a “mirabilia” which has been invested with

an evil spirit coming from Satan: a “mirabilia” which has become “magica.” On the

other hand, the earlier wonders in the valley, as well as episodes such as

that of the trolls in Bárðardalr, are plain “mirabilia.”

In his work on the fantastic in twelfth- and thirteenth-century French literature

and its links to the development of novelistic discourse, Francis Dubost has taken

Le Goff’s categories and shown that many works from this period willingly entertain

uncertainty about the nature of the supernatural their heroes are confronted with.

Is the marvel, be it Breton or other, just that and nothing else or can it be subsumed

under either of the two Christian categories, the divine or the diabolical? He distinguishes

between two types of medieval narrative. In one type the supernatural is taken for

granted as an aspect of the world in which the narrative takes place. He calls this

simply “le merveilleux.” In the other type, the reader—and very often the hero—is

made to ask himself whether

the supernatural event or phenomenon might be either divine or diabolical. He expresses

this tension with the following diagram where the curved arrows are meant to suggest

how the mirabilia are being drawn into either of the opposing categories of the Christian

world-view.

The works studied by Dubost have a clear tendency to formulate this questioning of

the supernatural, not from the point of view of the community or society, but from

the point of view of the individual. It is he who is trying to understand the nature

of what he is confronted with (Dubost 1992). Dubost calls this “le fantastique médiéval,”

adapting to the medieval mind-set Todorov’s concepts of “étrange” and “merveilleux.”

In contrast to nineteenth-century readers, the medieval subject believes in at least

some of what we call the supernatural: miracles really happen and the devil exists.

Thus the medieval “fantastique” occurs when the question arises whether the marvellous

is miraculous, diabolic or

just some kind of pagan wonder. The indecision concerning the nature of the supernatural

is therefore highly individualized. Instead of the focus being on the supernatural

per se it is on the individual experiencing the supernatural, i.e. on his subjective

self (Dubost 1991 231; Dubost 1993 56).

This is clearly what is happening in the Glám episode. The events are persistently

presented from the point of view of those who perceive them, but aren’t sure of what

to make of them. This uncanniness comes to its climax when Grettir looks into the

eyes of the monster. It is possible to show in detail how the narrative becomes increasingly

focalized on Grettir as it proceeds. At the end, no one but he looks the ghost in

the eye and this experience is the key to his tragic fate, the saga tells us, but

also the key to his personality.

This resonates with the historian Peter Brown’s article from 1975 on “Society and

the Supernatural.” He describes there the changing relationship between society and

the supernatural

in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when there is what he calls “a dramatic shift

in the borderline between the subjective and the objective” (143). Among several factors

he believes contribute to this mutation, three are relevant

to this article. The first is that public institutions become stronger and it is no

longer as necessary as it was before to invoke the supernatural in order to keep society

together. Ordeals, for example, are not allowed after the Fourth Lateran Council in

1215. A second factor, which has more direct bearings on Grettir’s Saga, is a displacement of the supernatural towards the inner sphere. Turning himself

inwards with the growing influence of the theology of intention, the individual is

increasingly attentive to the supernatural within him, that is to say to how the divine

and the diabolical manifest themselves in his soul. Divine Grace leading for example

to contrition after sin is an encounter with the supernatural which determines the

fate of the soul. This is what we are witnessing in Grettir’s Saga: the mystery of Glám’s supernatural status mirrors the uncertain identity of Grettir

as a moral being.

Dead fathers

Encounter with the supernatural is a key to the deeper layers of the soul in other

sagas than Grettir’s Saga. In Egil’s Saga, there is an intense, though seldom visible, conflict between Egil and his father,

which may be at the very core of the story of this enigmatic individual (Tulinius

forthcoming). It is expressed in supernatural terms at least two times in the saga.

In an episode from Egil’s youth, Skallagrim’s wolfish nature suggests that his identity

as a human is liminal. It is hinted that he can hamast, literally change shapes. This is done when he turns against his own son whom he nearly

kills (Egils Saga 101). The narrative is quite subtle in the way it entertains this uncertainty. However,

the underlying horror of a father wanting to kill his own son is maintained.

The second link between the supernatural and conflict between father and son in Egil’s

Saga, is when Skallagrim himself dies. Father and son have had an unfriendly exchange

earlier the same day. Egil has neglected to give his father the silver King Athelstan

awarded Skallagrim in compensation for the loss of Egil’s older brother Thorolf. Now,

Egil has made light of his father’s request for what is due to him. After they separate,

Skallagrim takes a chest of silver he owns and sinks it into a bog before returning

home to die, sitting in an upright position with his eyes open. When Egil comes home,

he must dispose of his father’s body. He goes into the room, taking care not to be

caught in his dead father’s gaze, lays the body down, closes its eyes and has a hole

made in the wall, so that it won’t be carried out through the door (Egils Saga 173-75).

This account has a direct parallel in Eyrbyggja Saga. Arnkell goði and his father Thorolf Lamefoot have had a fraught relationship. When

Arnkell refuses to assist his father in one of his schemes against his neighbours,

Thorolf dies in more or less the same circumstances as Skallagrim. Arnkell gives the

body the exact same treatment as in Egil’s Saga (Eyrbyggja Saga 91-92). The difference between the two accounts lies in the fact that Thorolf comes

back

as an extremely vicious revenant, whereas Skallagrim does not seem to. However, the

way Egil handles his father’s body more than suggests he fears Skallagrim might come

back to haunt him (Tulinius forthcoming).

Elsewhere, I have shown how the theme of dead fathers permeates Eyrbyggja Saga (2011). A semiotic analysis coupled with concepts from Freudian psychoanalysis,

reveals

how the narrative is working through the contradictions of the relationship between

sons and fathers. On the one hand, the father is a model to imitate and identify with;

on the other, he threatens and punishes. This is suggested in the saga through its

main conflict which is between Snorri goði, who is struggling to assert his inherited

power over the region, and Arnkell, who is more of a self-made man, and is competing

with Snorri for the position of dominant chieftain. Both of their fathers are dead.

However, Snorri’s father remains dead but is present as the one who gives him his

social status, along with his grandfather and great-grandfather, the Norwegian settler

Thorolf Mostrarskegg. Arnkell’s father, Thorolf, comes back as a revenant, as has

been seen. Therefore narrating the difficulties of acquiring power in a stateless

society also involves ghostly episodes. This can be related to the duality of the

father in Freudian theory: both the figure of the law, a model imposed on the son,

and the fearsome tyrant, he who threatens to castrate the son if he does not submit

to the law by repressing his desire for the mother. The revenant Thorolf Lamefoot

represents the sadistic and castrating father, whereas the memory of the other Thorolf,

Thorolf Mostrarskegg, Snorri’s great-grandfather, is the model he has to imitate.

Going back to Todorov’s concepts of “merveilleux,” “étrange” and “fantastique,” one

could say that in Eyrbyggja Saga we are not yet in the domain of the “fantastique,” as the saga evinces no uncertainty

as to the nature of the supernatural events. They

are pre-Christian marvels but it is not suggested, as in Grettir’s Saga, that they are the work of the Devil. In Egils Saga, however, the possibility of the paranormal is merely suggested, since Skallagrim

and Egil behave like Thorolf and Arnkell, but Skallagrim does not come back as a revenant.

There is however evidence indicating that the saga willingly entertains doubt concerning

that, and that he is somehow exacting retribution for Thorolf by causing the death

of Böðvar, Egil’s favourite son (Tulinius forthcoming).

The uncanny play of language

There is something terribly unsettling about deadly conflict between fathers and sons.

That is why it is the stuff of both myths and tragedies. It also seems to be that

of at least three of the sagas about early Icelanders. We have seen it in Egils Saga and Eyrbyggja Saga. Let us now turn again to Grettir’s Saga, thought to be considerably younger than both sagas and composed by someone who had

seemingly read both of them (Grettis Saga xxviii-xxix).

In a late episode of the saga, Grettir is uncharacteristically lenient in his dealings

with an opponent. Grettir has already been an outlaw for a number of years and is

now in hiding in the mountains of the Dalir area in western Iceland, preying on travellers

and the smaller farmers in the area. The young man’s name is Thorodd and he is son

to the powerful chieftain Snorri goði, the main character of Eyrbyggja Saga. Thorodd has behaved badly and Snorri has sent his son away, telling him not to come

back until he has killed an outlaw. Thorodd chooses Grettir, who proves to be more

than a match for the young man. However, Grettir refrains from harming him, claiming

it is because he fears Thorodd’s father and his wisdom (Grettis Saga 219-22).

This is far from being the most well-known passage of the saga, but there are many

noteworthy aspects to it. First of all, Grettir is quite frank about his feelings.

This is the first time he admits to fear of a real person and not a supernatural figure

or of Glám’s gaze which has haunted him ever since their encounter. Secondly, Grettir

shows considerable self-restraint, a quality that he has too little of. As King Olaf

says on the occasion of the failed ordeal, Grettir’s inability to control himself

is at the root of his ill fortune (Grettis Saga 134). Though this is not the first time that Grettir shows that he can control his

temper,

he has never before done so because of fear of a father-figure.

It is no coincidence that he calls Snorri “hærukarlinn,” which is a rare expression,

or that this scene takes place at precisely this point

in the saga. Grettir uses the word hærukarlinn to describe Snorri. It means “white-haired old man.” The first part hæru is the genitive plural form of hæra and means “grey hair.” It is also the first part of the nicknames of Grettir’s grandfather

Thorgrim “hærukollr” and his father Asmund “hærulangr.” It is also quite interesting

that the author—so fond of proverbs as is famously illustrated

by the ones Grettir uses as a child to infuriate his father—should let Snorri goði

say: “Margr er dulinn at sér.” I would translate this as: “Many are those who are

hidden to themselves.” For anybody interested in the Unconscious as it shapes behaviour,

language and works

of art, this cannot but sound familiar.

Grettir’s admission that he fears Thorfinn’s father can be understood in light of

Grettir’s childhood conflicts with his father. He shows time and again that he does

not fear his father. Using the language of proverbs, Grettir places himself on an

equal footing with Ásmundr. Indeed he shows considerably more verbal skills than his

father. Also, he has no qualms over inflicting physical pain on him when he scratches

his back so fiercely with the wool comb that it bleeds (Grettis Saga 36-42). Not fearing his father has possibly been Grettir’s problem throughout his

life but

now, as the end of the saga approaches, he finally admits to fearing a father.

This brings us back to the issue of self-restraint. One of Sigmund Freud’s discoveries

was that in order to learn to control its behaviour, the child must go through a period

in which it experiences intense fear of punishment by a third party, outside of the

mother-child dyad. This is usually the father or someone occupying his structural

place. This fear takes the form of castration anxiety because it is experienced—and

also repressed—in the same period that the child is discovering the physical difference

between the sexes. The child perceives the mother’s less obvious genitalia as an absence

of penis and assumes the father has castrated her. Experiencing this fear is an essential

part of becoming a socialized human being, of acquiring mastery over one’s desires

and undergoing the laws of human society. Neurotics experience a characteristic ambivalence

towards sexual difference, while perverts tend to deny it (Laplanche and Pontalis

282-87).

The Lacanian spin to this is that submitting to the arbitrariness of the Law also

precedes the entry into the world of language, i.e. Saussure’s famous arbitrariness

of the linguistic sign. The signifier is imposed on meaning by the force of the paternal

instance. It is a “coupure” or “cut” into reality. Our contact with the Real—in Lacan’s

sense of that word—is forever

severed by our entry into language, which at the same time heralds the repression

of our desires into the Unconscious. The threat of castration is thus intimately linked

with language. The Phallus, as symbol of what we have lost and yet desire, but also

of the power that threatens it, is what Lacan calls the master signifier. He also

calls it the Name-of-the-Father (Lacan 67; 150-154; 284; Evans 162-64).

As beings endowed with language, but also with both consciousness and an Unconscious,

we are engaged in a life-long struggle with meaning. We are constantly reacting to

the way language imposes its will on us, either by submitting to it or by refusing

it, or, as the poet does, by hacking away at it, playing with it, provoking it, undermining

the supremacy of the Name-of-the-Father over us (Lacan 159-71).

The term to hack away at the name of the father was chosen deliberately. In the episode we have just read,

it seems that a fragment of Asmund’s name, the four letters that form “hæru,” has

been dislodged from the paternal eponym and attached to Snorri. If Grettir is

not afraid of “hærulangr,” he does fear “hærukarlinn.” One could say that in Grettir’s

case this word is overdetermined as a signifier of

paternity, since both his father and grandfather have nicknames containing it.

We now come to the episode’s place in the saga. This is the period in the saga when

Grettir is closing the circle. The years of roaming around the country are over. They

were inaugurated by his fight with Glám and are now coming to an end. He will shortly

return to his mother and then go on to Drangey, where he will meet his death. Interestingly,

the episode just before this one is Grettir’s fight with the troll woman in Bárðardalr.

Many scholars have remarked on the parallels between this episode and that of the

fight with Glám. Both take place inside a farm, which is being subjected to intense

damage. In both cases Grettir waits inside until the monster invades the house and

in both cases he manages to prevail, though the opponents are manifestly stronger

than he is. However, there is a difference in how he disposes of his two foes. Glám

has his head cut off and placed between his buttocks. In Bárðardalr, it is the troll-woman’s

arm which is cut off.

The two episodes seem to be in dialogue with each other; if we pay attention to their

differences as well as to the circumstances in which they appear, we might reach a

better understanding about what the saga is telling us about Grettir and his fate.

In the troll-woman episode, Grettir’s ability to rid human dwellings of malevolent

supernatural creatures is re-affirmed. He is thanked for it, among others by a priest.

He also engages in his only love affair in the saga and fathers a child. As already

has been said, he shows unaccustomed restraint in the episode we have studied which

takes place immediately afterwards.

The Glám episode on the contrary is Grettir’s major traumatic experience. Even though

he prevails, the draugr has laid a curse upon him which has changed him. He cannot be alone at night, because

he is assailed by horrific visions and he has a much shorter temper. As he admits

to his uncle afterwards, he has more trouble containing himself and feels more strongly

about anything that might be perceived as an offence (Grettis Saga 122-23).

By his own admission, this is the only horrific sight that has ever affected him.

It incapacitates him so that he cannot brandish his sword and he feels almost as if

he is lying between the world of men and that of the dead. The text thus tells us

that this is an individual experience of the supernatural and also that it is the

individual experiencing himself. In addition, it is a profoundly traumatic episode,

which will relegate Grettir to a psychic stage of fear of the dark, being at the mercy

of hallucinations, losing his autonomy because he craves company.

Russell Poole has written that: “Glám’s role in the scheme of the narrative could

be formulated as that of overdetermining

characteristics of Grettir that have already manifested themselves in the hero’s heritage

and upbringing” (7). I agree that there is a deep connection between Grettir’s childhood

relationship

with his parents, the story of his ancestor Önund tréfótr (Grettis Saga 3-25) and what is going on between him and Glám. If we the readers of the saga are

spared

from the monster’s gaze, it is because there is more to Grettir’s dealing with him

than meets the eye.

During their struggle, they end up outside, Grettir lying on top of Glám. It is then

that the moon shines on the monster’s face and Grettir sees his gaze. What horrors

does Grettir see in Glám’s eyes? A death threat, obviously, but from whom? It is here

that I think that the Lacanian approach is useful. What does Grettir do to the body

of the draugr after he has recomposed himself? By cutting his head off and putting it “við þjó

honum,” i.e. close to his buttocks, one could say that he is also recomposing his

opponent’s

body.

Of course there is a folkloristic reading of this episode. As in many other Icelandic

stories, and probably those of other countries, doing this is a way to keep the evil

spirit contained. This does not however exclude other interpretations and I would

argue that Grettir is treating Glám’s body like a signifier, transforming it to give

it a meaning, possibly the deeper meaning of his life. He is taking away the seat

of the horrific eyes in which he sees himself close to Hel, and the mouth which has

cast on him the spell of his tragic destiny. The head is the seat of phallic power,

the power of language and also of castration. It is the terrible unspeakable force

of the paternal instance, a power which psychoanalysis tells us we acknowledge in

our submission to laws and rules, notably those of language, but of which we also

repress our knowledge.

Grettir is taking this sign and putting it somewhere else, in the cleft between the

legs, the crotch. By lying on top of Glám, he was in a way casting him as a female,

or more precisely as the phallic mother. By putting the sign of the father back where

it wasn’t, i.e. between the legs, he is symbolically denying castration.

The floating signifier

Very much in line with the Lacanian approach, this play on the signifier can also

be seen in the way the name of Grettir’s father, Ásmundr, comes back (gengr aptr)

in the name of the revenant (“aptrganga”):

What Grettir does to the body of the castrating and judging figure is paralleled by

the author’s work on the name of the father. To create Glám, two words have been taken

out of Ásmundr’s name and eponym, the word “und” or the wound, which is the result

of castration, and “hæru,” the grey hairs which are a signifier of paternity in Grettir’s

male lineage.

What Grettir does to the body of the castrating and judging figure is paralleled by

the author’s work on the name of the father. To create Glám, two words have been taken

out of Ásmundr’s name and eponym, the word “und” or the wound, which is the result

of castration, and “hæru,” the grey hairs which are a signifier of paternity in Grettir’s

male lineage.

Significantly, both of these displaced fragments resurface around the same time in

the saga. Mention has already been made of the paternal signifier used to characterize

Snorri goði: “hærukarlinn faðir þinn.” The wound (“und”) that had been taken away

re-appears in the fight with the troll woman. Indeed, Grettir

does to her the exact opposite of what he does to Glám. Instead of putting back the

absent phallus, he cuts it away, when he cuts her arm off. Symbolically, it can be

construed, he is acknowledging sexual difference at the same time he is undergoing

the law. It is therefore highly significant that it is at this point that Grettir

is able to sire his own son (Grettis Saga 219).

The dialectic relationship between fragmenting the name of the father and making it

whole again is therefore one of the ways in which fiction is engendered in the saga.

There are several more examples of this in the saga, especially in the story of Grettir’s

ancestor, Önund tréfótr, “the most able-bodied one-legged man in days of yore” (Grettis Saga 25-26), but also in the way Grettir is finally killed. It is no coincidence that

death comes

to him in the form of a floating signifier, i.e. a log inscribed with magic runes

and powered by a spell cast by a broken-legged woman (Grettis Saga 249-51). Like Önund’s wooden leg that fools his opponent allowing him to cut off

his head

(Grettis Saga 12), the log that brings about Grettir’s demise deflects his own lack of restraint

upon

himself. His leg has almost rotted away when Thorbjorn executes him. However Grettir

will not relinquish the phallic sword. His hand has to be cut off his dead body, his

“axlar fótr” [foot of the shoulder] as his brother Thorstein laters calls it in verse.

Not until that has been done,

does Grettir let go of it (Grettis Saga 261; 275).

In psychoanalytic terms, Grettir’s tragedy is that of the denial of castration, and

therefore of the refusal to submit to the law. It is quite remarkable that medieval

Iceland’s most famous and popular outlaw saga should link together in such an intricate

way his outlawry, the trauma of his encounter with the supernatural and his story

as an individual.

Conclusion: sagas, novels and the Uncanny

For the South African novelist, André Brink, what defines the novel from its inception

is its deep engagement with language. The play of language in Grettir’s Saga has been studied effectively by Laurence de Looze, and Heather O’Donoghue (180–227).

Both insist on the relationship between the development of fictional prose narrative

and the practice of skaldic poetry in the sagas about early Icelanders, as I have

done elsewhere (2000b). It is easy to imagine why authors, who are so involved in

the intricate play of

meaning in complex poetry, would also produce artful narrative. In another vein, William

Sayers has commented on the links between the representation of revenants and the

evolution of saga-writing in relation to historical developments in Iceland in the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. I believe this article combines these approaches

and also adds something to what these and other scholars have said about encounters

with the paranormal in Grettir’s Saga and other sagas about early Icelanders. It also contributes to understanding how

these sagas belong to the general trend in Western culture leading to the development

of the novel as an art form.

By applying Dubost’s inspired approach to what he calls “le fantastique médiéval”

to the sagas, I have been able to show that the presence of the supernatural in what

many perceive as basically realistic stories is an essential part of what makes them

novelistic. This can be related to a third factor of change in the relationship between

society and the supernatural as described by Peter Brown, which is of relevance here

and which hasn’t been mentioned yet: In the renaissance of the twelfth century, dependence

on authority and Revelation decreased, which led to an increased reliance on the powers

of mind and language to know the world (143). This new intellectual self-confidence

is visible in these sagas, as in the works

of all those who are contributing to the development of the novel, from Chrétien de

Troyes onwards. Through their narratives, they are testing their world view, which

means both constructing it and undermining it.

The use of Bakthin’s concept of the chronotope makes intelligible why this type of

exploration is particularly noticeable in the sagas about early Icelanders, compared

to other Old Icelandic genres. The thirteenth-century authors and audience of the

sagas are going through a period of change and redefinition of society. The literary

representation of the period in which it originated, socially, politically, and spiritually,

is an “other scene” in which they can contemplate their own uncertainties. For a medieval

Christian the

essential uncertainty is about what will happen to the soul. After the twelfth century,

the supernatural happens within the soul. Psychoanalysis provides theoretical tools

that allow us to determine how the literary representation of encounters with the

paranormal in the shadow world of the pre-Christian past open up avenues into the

more uncanny aspects of the human soul. As one theorist of literature has recently

said, the uncanny “is essentially to do with hesitation and uncertainty” (Royle 19).

NOTES

- An earlier version of this article appeared as “Framliðnir feður: Um forneskju og frásagnarlist í Eyrbyggju, Eglu og Grettlu” in Heiðin minni: Greinar um fornar bókmenntir, pp. 283–316, edited by Haraldur Bessason and Baldur Hafstað, Reykjavík: Heimskringla, háskólaforlag Máls og menningar, 1999.

Bibliography

- Auden, W.H. 1968.

The World of the Sagas.

Secondary Worlds. New York: Random House. 47-84. - Bakhtin, Mikhaïl. 1981.

Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel. Notes Towards a Historical Poetics.

The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. 84-258. - Bayard, Pierre. 1994. Maupassant, juste avant Freud. Paris: Éditions de minuit.

- Brink, André. 1998. The Novel: Language and Narrative from Cervantes to Calvino. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Brown, Peter. 1975.

Society and the Supernatural: A Medieval Change.

Daedalus 104.2: 133-51. - De Looze, Laurence. 1991.

The Outlaw Poet, the Poet Outlaw: Self-consciousness in Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar.

Arkiv för nordisk filologi 106: 85-103. - Doody, Margaret Anne. 1996. The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Dubost, Francis. 1991. Aspects fantastiques de la littérature narrative médiévale (XIIème et XIIIème siècles). L’autre, l’ailleurs, l’autrefois. Geneva: Slatkine.

- ⸻. 1992.

Le conflit des lumières: lire "tot el" la dramaturgie du Graal chez Chrétien de Troyes.

Le Moyen Âge 98: 187-212. - ⸻. 1993.

La pensée de l’impensable dans la fiction médiévale.

Écriture et modes de pensée au Moyen Âge (VIIIe-XVe siècles). Ed. Dominique Boutet and Laurence Harf-Lancner. Paris: Presses de l’École normale supérieure. 47‑68. - Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar. 1933. Ed. Sigurður Nordal. Íslenzk fornrit. 2. Reykjavik: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Eyrbyggja saga. 1935. Ed. Einar Ól. Sveinsson and Matthías Þórðarson. Íslenzk fornrit 4. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

Hallfreðar saga.

1939. Vatnsdœla saga, Hallfreðar saga, Kormáks saga, Hrómundar þáttr halta, Hrafns þáttr Guðrúnarsonar. Ed. Einar Ól. Sveinsson. Íslenzk fornrit 8. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.- Evans, Dylan. 1996. An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

- Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar. Bandamanna saga. Odds þáttr Ófeigssonar. 1936. Ed. Guðni Jónsson. Íslenzk fornrit 7. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Harris, Joseph. 1986.

The Saga as Historical Novel.

Structure and Meaning in Old Norse Literature: New Approaches to Textual Analysis and Literary Criticism. Ed. John Lindow, Lars Lönnroth, and Gerd Wolfgang Weber. The Viking Collection 3. Odense: Odense University Press. 187-219. (Repr. in “Speak Useful Words or Say Nothing”: Old Norse Studies. Ed. Susan E. Deskis and Thomas D. Hill. Islandica 53. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 2008. 227-60.) - Jackson, Rosemary. 1981. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. London and New York: Methuen.

- Jakobsson, Ármann. 2005.

Royal Biography.

A companion to Old Norse-Icelandic literature and culture. Ed. Rory McTurk. Oxford: Blackwell. 388-402. - Kristjánsson, Jónas. 1988. Eddas and Sagas: Iceland‘s Medieval Literature. Trans. Peter G. Foote. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag.

- Kundera, Milan. 1988. The Art of the Novel. Trans. Linda Asher. London: Faber and Faber.

- Lacan, Jacques. 1977. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton.

- Laplanche, J., and J.-B Pontalis. 1973. The Language of Psychoanalysis. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Hogarth Press.

- Le Goff, Jacques. 1985.

Le merveilleux dans l’Occident médiéval.

L’imaginaire médiéval. Paris: Gallimard. 17-39. - McKeon, Michael. 2000. Theory of the Novel: A Historical Approach. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mundal, Else. 2011.

Íslendingabók: The Creation of an Icelandic Christian Identity.

Historical Narratives and Christian Identity on a European Periphery: Early History Writing in Northern, East-Central, and Eastern Europe (c. 1070-1200). Ed. Ildar H. Garipzanov. Turnhout: Brepols. 111-21. - Nordal, Sigurður. 1940. Hrafnkatla. Studia Islandica. Íslensk fræði 7. Reykjavík: Ísafoldarprentsmiðja H.F..

- O’Donoghue, Heather. 2005. Skaldic Verse and the Poetics of Saga Narrative. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ólason, Vésteinn. 1998. Dialogues with the Viking Age: Narration and Representation in the Sagas of the Icelanders. Trans. Andrew Wawn. Reykjavík: Heimskringla.

- Pálsson, Herman. 1992.

Um Glám í Grettlu: Drög að íslenskri draugafræði.

The International Saga Society Newsletter No. 6: 1-8. - Pavel, Thomas G. 1986. Fictional Worlds. Cambridge Mass. and London: Harvard University Press.

- Poole, Russell G. 2004.

Myth, Psychology, and Society in Grettis saga.

alvíssmál. Forschungen zum mittelalterlichen Kultur Skandinaviens 11: 3–16. - Royle, Nicholas. 2003. The Uncanny. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Sayers, William. 1996.

The Alien and Alienated as Unquiet Dead in the Sagas of the Icelanders.

Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 242-63. - Scarpetta, Guy. 1996. L’Âge d’Or du Roman. Paris: Grasset.

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1975. The Fantastic : A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Trans. Richard Howard. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

- Tulinius, Torfi H. 1997.

Le statut théologique d’Egill Skalla-Grímsson.

Hugur: mélanges d’histoire, de littérature et de mythologie offerts à Régis Boyer pour son 65e anniversaire. Ed. Claude Lecouteux and Olivier Gouchet. Paris: Presses de l’Université Paris-Sorbonne. 279-88. - ⸻. 2000a.

The Matter of the North: Fiction and Uncertain Identities in Thirteenth-Century Iceland.

Old Icelandic Literature and Society. Ed. Margaret Clunies Ross. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature 42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 242-65. - ⸻. 2000b.

The Prosimetrum Form 2: Verse as the Basis for Saga Composition and Interpretation.

Skaldsagas: Text, Vocation and Desire in the Icelandic Sagas of Poets. Ed. Russell G. Poole. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 27. Berlin: Gruyter. 192-217. - ⸻. 2011.

Revenants in Medieval Icelandic Literature.

Caietele Echinox 21: Fantômes, Revenants, Poltergeists, Mânes. - ⸻. Forthcoming. The Riddle of the Viking Poet. Egils Saga and Snorri Sturluson. Islandica. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Library.

- Vatnsdæla saga. Hallfreðar saga. Kormáks saga. Hrómundar þáttr halta. Hrafns þáttr Guðrúnarsonar. 1939. Ed. Einar Ólafur Sveinsson. Íslenzk fornrit. 8. Reykjavik: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Watt, Ian. 1957. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Winroth, Anders. 2012. The Conversion of Scandinavia: Vikings, Merchants, and Missionaries in the Remaking of Northern Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Zink, Michel. 1985. La Subjectivité Littéraire: Autour du Siècle de Saint Louis. Écritures 25. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.