SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 19 (2010) pp.128-143.

Title: From Working Class Drama to Academic Showdown: On Carl Th. Dreyer’s Use of His Literary Source in Två Människor [Two People] (1945)

Author:

Morten Egholm

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Richard Baer

Marked up by

Richard Baer

Statement of responsibility:

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal

Source(s):

Egholm, Morten. 2010.

From Working Class Drama to Academic Showdown: On Carl Th. Dreyer’s Use of His Literary Source in Två Människor [Two People] (1945).Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 19: 128-143.

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- Två människor [Two People]

- Somin, Willy Oscar

- Dreyer, Carl Theo.

- cinema and psychology

- cinema of social engagement

- cinematic adaptation

- Danish cinema

- RAB: started markup 31st August 2010

- MDH: fixed missing @level attributes on title elements 13th September 2010

- MDH: fix for some titles, and addition of one biblio item 16th September 2010

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 15th November 2010

- 22nd August 2011 MDH: Corrected "Swedish" to "Swiss" in the first paragraph of the article on author's instructions.

- MDH: added page numbers from print journal edition 11th April 2012

From Working Class Drama to Academic Showdown: On Carl Th. Dreyer’s Use of His Literary Source in Två Människor [Two People] (1945)

Morten Egholm

ABSTRACT: The aim of the article is to analyze Danish film director Carl Th.

Dreyer’s motives for using Willy Oscar Somin’s play Close

Quarters (1935) as a source for his twelfth feature film, Två

Människor [Two People] (1945). This film is almost completely forgotten today,

in part because the director himself chose to disown it, but in part because

film historians have hitherto been unable to locate its exact textual source. My

concern has been to examine how loyal Dreyer actually wanted to stay to the

themes and narrative of his source. Newly discovered archival material

demonstrates that Dreyer actually thought of making a more political movie. This

material leads to a more general discussion of Dreyer as an adaptor of literary

works. I conclude that Dreyer made Två Människor in a period of

his directing career where he wanted to distance himself from his literary

sources.

RÉSUMÉ: Cet article a pour but d’analyser les raisons qui ont motivé le réalisateur

danois Carl Th. Dreyer à utiliser la pièce de Willy Oscar Somin, Close Quarters (1935), comme source de son douzième film Två Människor [Deux Êtres] (1945). Ce film est pratiquement oublié aujourd’hui, d’une part parce

que le réalisateur

a lui-même choisi de le renier, mais également parce que les historiens avaient été

incapables jusqu’à présent d’en situer la source textuelle. J’ai voulu examiner à

quel point Dreyer voulait rester fidèle aux thèmes et au récit narratif de sa source.

Des documents d’archive récemment découverts démontrent que Dreyer pensait en fait

réaliser un film plus politique. Ces documents amèneront une discussion plus générale

au sujet de Dreyer et de son travail d’adaptation d’oeuvres littéraires. J’en conclue

que Dreyer a réalisé Två Människor à un moment de sa carrière où il désirait se distancer de ses sources littéraires.

Very little has been written about Danish film director

Carl Th. Dreyer’s (1889-1968) use of literary sources. A notable example of this

silence is the absence of comment on his use of a Swiss literary source to

create Två Människor [Two People], (1945), a film he directed during his exile in

Stockholm at the end of the war.

This failure to focus on Dreyer as an adaptor would appear to be strange, for

apart from his second feature—Blade af Satans Bog [Leaves from Satan’s Book] (1919), which is based not on a literary

source but on an original screenplay written by the Danish playwright Edgar

Høyer in 1913—all thirteen of his other feature films are based on novels, short

stories, or plays. But then most Dreyer scholars tend to look at Dreyer as an

auteur who used mediocre literary sources, which are

otherwise totally forgotten today, only as an excuse for developing his own

visions and his unique cinematic style (Neergaard, Drouzy,

Kau).

There’s an element of truth to this view, but recent research has shown that in

many of his films Dreyer demonstrates a real thematic and narrative loyalty to

the sources. As shown in my dissertation Dreyer’s use of literary sources can be

divided in to three phases: 1) 1913-1926: a period marked by his loyalty to his

sources with the aim of raising film’s artistic status (seven early silent

films); 2) 1927-1947: freer use of sources in order to highlight film’s

independence as an art form (four films: La Passion de Jeanne

d’Arc [1928], Vampyr [1932], Day of

Wrath [1943], and Two People [1945]); 3) 1948-1964: a

high degree of loyalty to sources combined with a strong awareness of the

different aesthetic potentials of literature and film (a short film: They

caught the Ferry [1948], and two feature films: Ordet

[1955] and Gertrud [1964]).

During the first phase Dreyer specifically recommends a surprisingly high degree

of faithfulness in an article written in 1922, “Nye Ideer om

Filmen” [New Ideas About the Film], where he observes that

“filmens opgave er og bliver den samme som teatrets: at

tolke andres tanker” [the task of the cinema is and will remain the same as that of

theatre: to interpret the thoughts of others] (1964 22; 1973 33 [emphasis in the original]). Actually he is here

discussing adaptation with his colleague, Benjamin Christensen who was agitating

for a new kind of film director, a director that best could be described as a

poet of pictures. Christensen is here the director who is ahead of his time,

while Dreyer is the conservative one. Thus it is interesting that Dreyer—who

later would be hailed as one of greatest auteurs in film history—in most of his

career saw himself as an interpreter of other’s thoughts. It is this paradox

that makes it interesting to analyze what Dreyer actually did when he

transformed literary texts into film.

Willy Oscar Somin’s Swiss-German play Attentat [Attack] (1934) has always been acknowledged as the source of

Dreyer’s twelfth feature, Två Människor, but little has ever been

made of this dependence for the simple reason that it has been impossible to

track down a published version of the original source. Jan Olsson has written

two articles on the film (1983, 2005), but in these

Somin’s play is only mentioned very briefly. More importantly, Olsson refers

only to a putative German version, whereas Dreyer actually based his film on an

English version of the play, as I will demonstrate. Furthermore, this film is

considered Dreyer’s greatest failure as a director: thus it only ran for five

days in Stockholm (March 23 to March 27, 1945), and it never had an official

première in Denmark. Whatever the cause for this lack of success, which has been

attributed to the refusal of Swedish producers to let him have the actors he

wanted (Drum and Drum 198-99), for the rest of his life

Dreyer chose to disown the film.

The aims of this article are to analyze Dreyer’s motives for using Somin’s play

and to explore the overall vision that informs Två Människor.

What I hope will emerge is how loyal Dreyer was to his source on two levels: a

thematic and a narrative one. These are the two levels where it seems most

relevant to compare the two works, since the source is a theatre piece, and the

film is from a stylistic point of view quite loyal to its source. Dreyer uses a

number of interesting camera angles and shadow/light-effects, but in general his

film is very theatrical.

The intense psychological portrait

Although he seems not to have had any prior interest in Oscar Somin, a now

completely forgotten German-Jewish exile who lived in Switzerland during the

Nazi era, Dreyer was drawn to his play, Attentat. What in

particular interested Dreyer can be discerned from the title under which the

1945 film was released: Två Människor—[Two People].

In other words it was the complex psychological play between two human beings

emotionally tied to each other that Dreyer wanted to immerse himself in. It was

a desire he had nurtured for many years when on December 17, 1944, he signed a

contract with Carl Anders Dymling, the director of Swedish Film Industry. If

this cinematic exercise was to be based on a play, the range of possible

properties was limited for the cast could only comprise two persons.

Attentat supplied such a plot, and a highly melodramatic one

at that, as a plot summary will reveal: Dr. Arne Lundell, doctor at a mental

hospital, has written a paper. His superior, Professor Sander, publishes a paper

with the same results at the same time and accuses Arne of having plagiarized

his work. The truth is that Sander, under the pretext of helping Arne, has

forced Arne’s wife, Marianne—who was formerly Sander’s mistress—into showing him

a draft of the paper. Sander threatens to ruin Arne’s career unless Marianne

leaves Arne and marries him. Instead, she shoots Sander. Since Arne was near

Sander’s home at the time of the murder, he becomes the prime suspect. Marianne

then reveals the truth to Arne who wants to save her by taking the blame for the

murder, but she takes poison, and Arne follows her in death.

Given such a plot it is not difficult to believe that Dreyer would have

preferred making an adaptation of Louis Verneuil’s play Monsieur

Lamberthier ou Satan (1928), which had a successful Broadway run

under the title Jealousy.

According to Luft (1956)

Dreyer wanted to do it, but author Louis Verneuil had sold the screen rights to Warner Brothers, who enlarged the set of characters to a normal-size cast, called the picture Deception (1946) and starred Bette Davis, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains.

Verneuil’s play actually has a lot in common with Dreyer’s film and the Somin

play, since it also describes a complex, but genuinely loving relationship

between a man and a woman who continues to suffer the lingering effects of

sexual repression. Jealousy enters the relationship with fatal consequences.

Another element the three narratives have in

common is the important informational role external sounds play, especially the

use of radio spots and telephone calls. Although the following analysis will

show that Dreyer didn’t stay entirely loyal to the Somin play, his departures

from his source cannot be attributed to the influence of Verneuil’s play, except

for one detail to which I will return below. The main plot and character

development is definitely taken directly from Somin.

Though Två Människor allowed Dreyer to explore one of his

favourite genres—the chamber drama —his choice of Somin’s play must largely be

seen as a compromise forced upon him by the impossibility of addressing the work

that interested him more. Helping to confirm the supposition that Dreyer wasn’t

particularly interested in Somin as a writer is the fact that he chose not to

base the screenplay on the original German text, but instead on the English

adaptation called Close Quarters.

Yet Dreyer’s choice of the English version was probably determined by its

easier availability and greater commercial success. Close Quarters

premiered in London, June 25, 1935, at the Embassy Theatre and was released the

same year in book form in a volume called Famous Plays of 1935.

In March 1939 the play was also staged eight times at the John Golden Theater on

Broadway.

Even though we do not know very much about Somin’s life and work, what little we

do know indicates that he was a writer whom Dreyer would have found sympathetic,

among other reasons for his opposition to fascism, since Dreyer throughout his

whole life and professional career was against anti-semitism and political

fanaticism. Along with Heinz and Cassie Michaelis, Somin in 1934 released two

critiques of National Socialism, The Brown Culture [Die Braune Kultur] and The

Brown Hate [Der braune Haß], works that share the aim set out on the very last page

in the former work: “‘Die braune Kultur’ und ‘Der braune Haß’

ergänzen sich, um der Welt klar vor Augen zu führen: die braune

Gefahr.” [“The Brown Culture” and “The Brown Hate” complement one another

in presenting this to the eyes of the world—the brown

danger.] (Somin, Michaelis and Michaelis 324).

The Brown Culture is

as a political-polemical work, written as a warning against the young Nazi

regime that in 1934 had already caused an extensive emigration, including—among

others—the emigration of Somin himself. Conversely immigration with all its

problems also plays a significant role in Close Quarters for it

depicts someone who has immigrated to a country that is probably meant to be

Germany. Besides, the play contains some more or less obvious allusions to the

many fascist regimes that were on the march in 1930s Europe. It isn’t possible

to say whether Dreyer was aware of the two books, but there is no doubt that he

shared Somin’s view of the Nazi regime.

But let us return to the question of Dreyer’s loyalty to the thematic focus of

his source. We will direct our attention to two aspects of this question: 1) How

much of the political conflict so crucial to the play has Dreyer included in his

film? 2) Is the psychological portrait of the female protagonist (Liesa in the

play, Marianne in the film) identical in the Somin source and Dreyer

adaptation?

Political conflicts or “un drame de passion”?

Close Quarters can first of all be described as a political play.

Although the whole play comprises just a series of emotional discussions between

the two members of a married couple in two different locations, political

behaviour and abstract political mechanisms are integrated into the action of

the play as a part of the crime plot and the psychological drama around which it

is built. The play takes place in a modest, working class apartment; the

characters use a hard-hitting, unostentatious and ironic language when emotional

issues are being discussed. In many ways the tone of the play can be seen as a

typical of that used in many European social-realist novels of the 1930s,

including for example Falada’s Little Man, What now? (1932).

Somin introduces his male protagonist, emigrant Gustav Bergmann, by describing

him as “an honest idealist and something of a

fanatic” (232). The action of the opening sequence is

also given a political inflection, in that it describes how Gustav’s wife

Liesa—after an anxious wait—meets her husband with open arms when he returns

from a socialist meeting where he was one of the speakers agitating for a

general strike. The event that triggers the central conflict is also closely

linked to the political dimension, since the Sander of the play—who has been

found murdered in the woods the same evening Gustav returns from his political

meeting—is Minister of Internal Affairs in a Central European country that might

be Germany in the 1930s. Arne becomes a prime suspect, simply because he is

Sander’s political opponent. Most of the play describes the anxiety between the

husband and wife, and just as everything is pointing at Gustav, Liesa confesses

that it is she who has murdered Sander, primarily because he—as her former

lover—pressured her to get information about the political strategies of

Gustav’s political party. When they finally realize that the noose has tightened

on them, Gustav chooses offstage to shoot first Liesa, then himself.

Subsequently a radio that has been left playing reveals that crucial evidence

has been found at the crime scene pointing away from Gustav—so the double

suicide was unnecessary, although it serves as a device by which the couple are

released from their inner guilt.

During the many passionate discussions in the apartment we get a general idea of

Gustav’s political convictions. In many ways he seems to be agitating for a

classical socialist humanism when he says: “I’ve worked and slaved all my

life for one ideal. Equality. The equality of the human race. For years

I’ve struggled against the preferences of classes and fought for man’s

rights” (271). The crime plot is also woven into

Gustav’s political project, and the murder of Sander generates a discussion

about the death penalty. Gustav’s position is here quiet clear: “I hate

and loathe capital punishment. For years—ever since I came to this

country—I’ve fought against it” (247). This doesn’t

make his position as the prime suspect less problematic: “And what about

my fight against capital punishment? A suspected murderer who has just

managed to escape the Gallows! Nobody believes a man if they think he’s

talking in his own interests—unless they think it’s in their interest,

too” (251). “An execution is nothing but

legalised murder” (259). The discussion of the death

penalty can obviously be seen as an important political criticism of the fascist

dictatorships in 1930s Europe. In that way Close Quarters is only

a chamber drama on the surface; beneath we find thematic elements of a political

sort that could not be addressed directly in a number of countries in Europe

during the 1930s.

With his adaptation, Dreyer removes the story completely from its political and

historical context. There is no doubt that it was Dreyer himself who wanted to

play up the personal dimension, for he wrote in a letter to producer Dymling

January 9, 1944:

Herved sender jeg Udkastet til Filmen over ”Close Quarters.” Fire af Filmens mindre Scener har vi fuldt udarbejdet for at give et Indtryk af Stil, Figurer, Dialog og Atmosfære. Hvad vi har tilstræbt er ikke saa meget at lave en ’thriller’ som ’un drame de passion’—en psykologisk Studie, der kan give to Skuespillere Anledning til et fremragende Spil. Og i øvrigt at bringe noget Erotik og menneskelig Varme ind i Handlingen.

First of all Dreyer has chosen to make his protagonists academics rather than working class people. The language is no longer dominated by everyday expressions, but stylized, idealised and sometimes quite pretentious. Dreyer has also added a small love poem by Swedish writer Bo Bergman, which is quoted and analyzed by the two lovers during their long discussions, and an Italian lullaby, sung twice by Marianne. In order to introduce physical, dynamic movement into the stylised rooms where almost all the action takes place, Dreyer lets Marianne perform a small erotic dance for her husband, which is not to be found in the play. The main conflict no longer turns on a political struggle, but which of the two scientists has stolen results from the other. But the basic structure of the plot line is the same. It is important, though, to mention the different ways in which the two works present the double suicide with which each ends: in Somin’s play it happens offstage, but in Dreyer’s film we are invited into the bedroom where Arne dies in his wife’s arms.[I hereby send you my draft to the film based on Close Quarters. We have worked with four of the smaller scenes to give you an impression of style, characters, dialogue and atmosphere. What we have sought is not so much to make a “thriller” as “un drame de passion”—a psychological study that should make it possible for the actors to show all their excellent skills. And at the same time the idea has been to bring a more erotic atmosphere and some human warmth into the plot.]

Dreyer’s ambition has been to transform a political play discussing social

issues into at passionate psychological drama. This is also confirmed by a

letter he sends to his friend, the film scholar Ebbe Neergaard, in 1949:

Handlingen i ”To Mennesker” er blevet kaldt banal, men er Sandheden ikke, at næsten alle “crimes passionelles” i Virkeligheden er banale? Og Formaalet er jo slet ikke at lave en udspekuleret Kriminalfilm. Tværtimod. Hvad jeg ønskede som Baggrund for den psykologiske Konflikt mellem de to Mennesker, var en ganske enkel, sandsynlig og om jeg saa maa sige ”dagligdags” Politisag om et Mord. Selve Mordet var af underordnet Betydning—det var bare Midlet til det, som for mig var Maalet, nemlig at vise de Hændelser af psykologisk Art, der blev Følgen af Mordet, og som endte med at drive de to Mennesker i Døden.

[The plot in Two People has been called banal, but isn’t it the case that all “crimes passionelles” are actually banal? And my main purpose wasn’t to make a crime movie with a complicated plot line. All I wanted as background of the psychological drama between two people was, if I may say so, an “everyday” police case about a murder. The murder itself was of secondary importance—it was just the means to what for me was the goal, namely to focus on the psychological consequences of the murder that eventually drove the two people to death.]

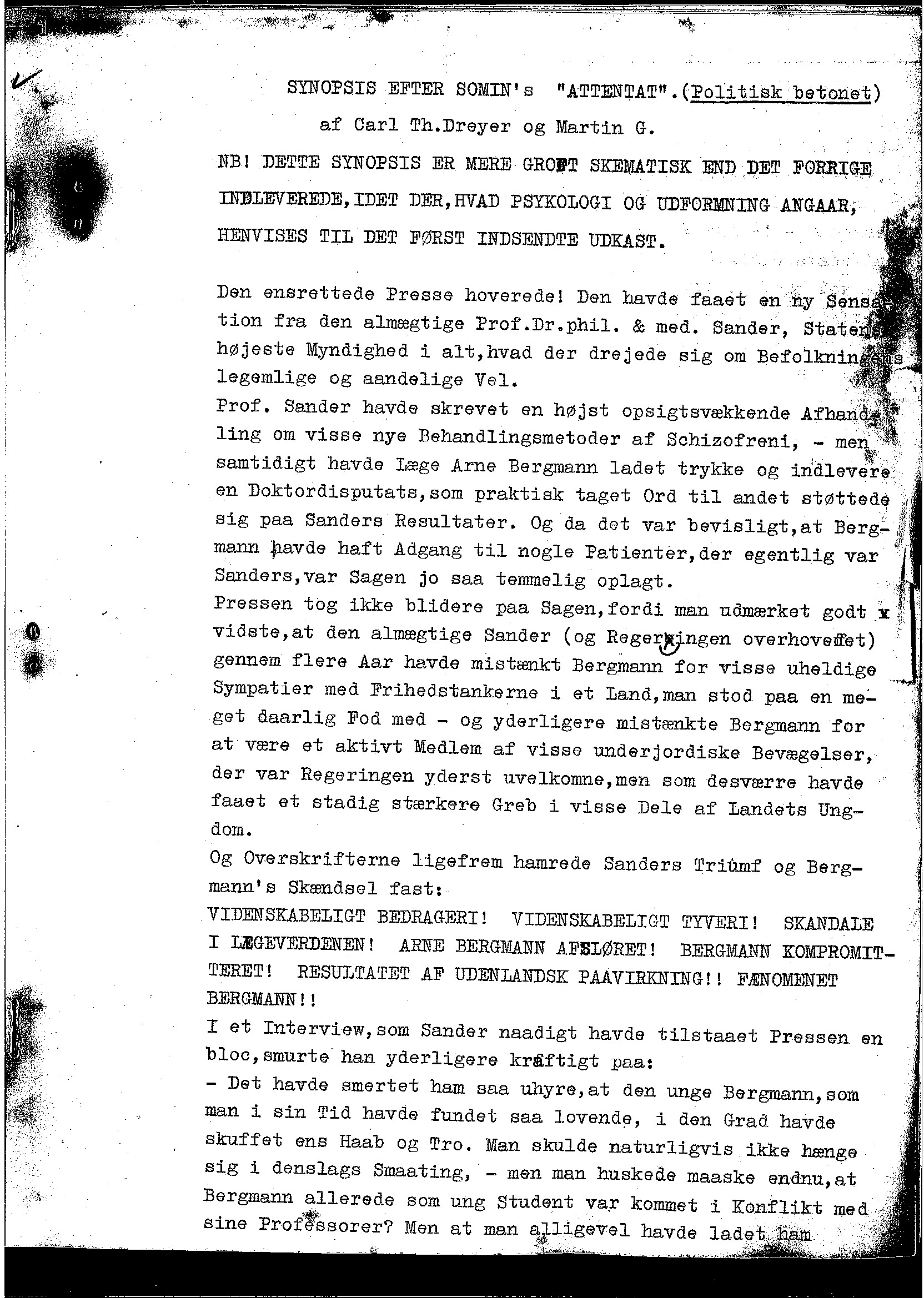

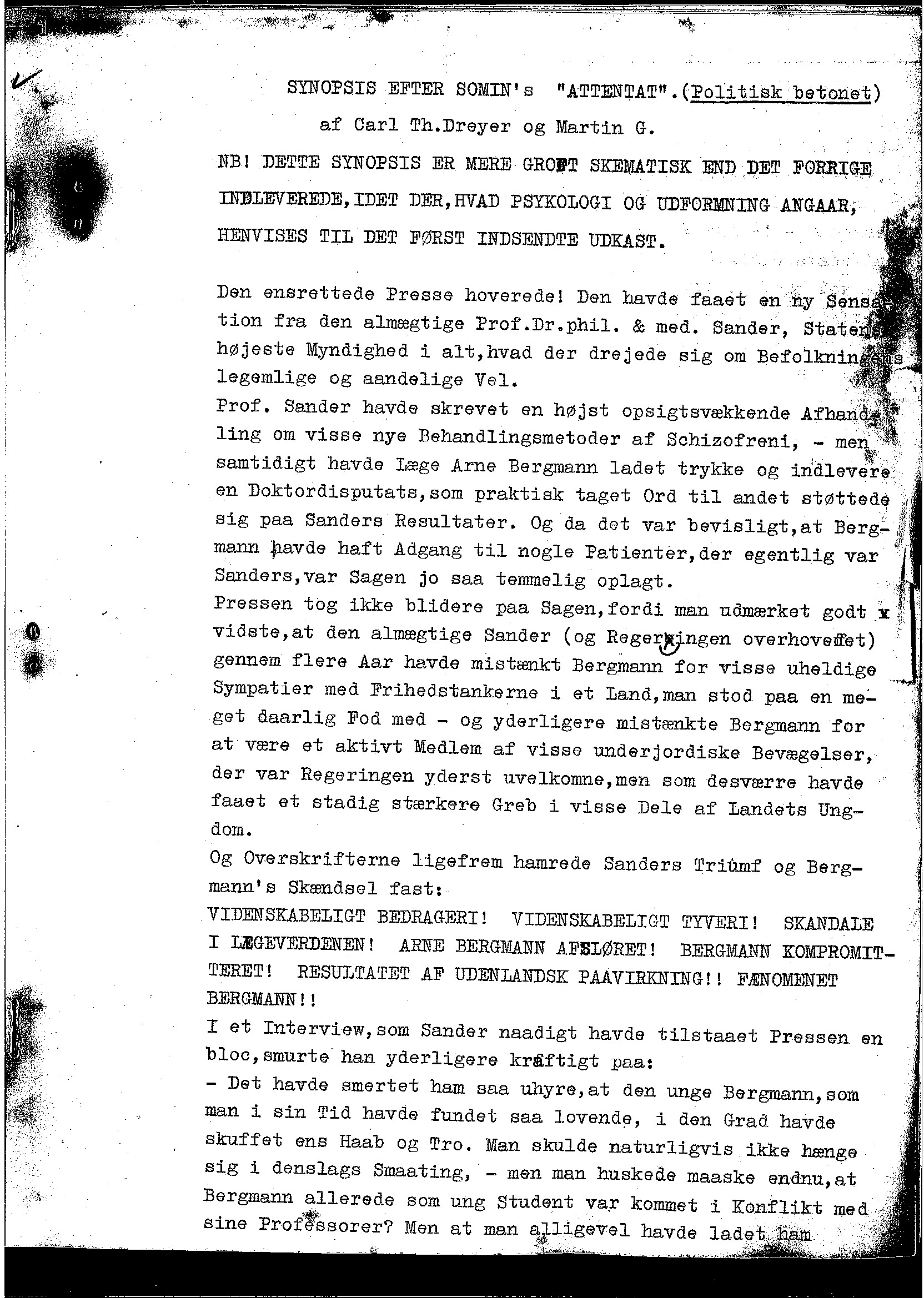

But was Dreyer wholly reluctant to make a film with an obvious political agenda?

Most Dreyer scholars would be inclined to say yes, including the author of this

article. But the truth seems more complex, as I discovered recently when going

through Dreyer materials in the Swedish Film Institute’s library. In this

archive there exists an undated 12-page synopsis that Dreyer along with Danish

writer (and Jewish refugee) Martin Glanner wrote in the early stages of working

on the film. The title of the synopsis is Attentat (Politisk

betonet) [Attack (stressing the political)], and Dreyer and Glanner here

combine the scientific conflict with a very political one. Dreyer had already in

this phase of the scriptwriting decided to let the protagonists be academics.

But into the plot about stealing scientific results is intermingled a secondary

political plot about press censorship in a dictatorship somewhere in Europe. In

this version, Arne is a political figure who for several years has been

suspected by the government of working in the country’s freedom movement.

Actually, the Arne in the synopsis is an even more political figure than Gustav

in Somin’s play, since it is often mentioned how inspired the youth is by his

ideal of freedom (7). Further, we are told that

writer (and Jewish refugee) Martin Glanner wrote in the early stages of working

on the film. The title of the synopsis is Attentat (Politisk

betonet) [Attack (stressing the political)], and Dreyer and Glanner here

combine the scientific conflict with a very political one. Dreyer had already in

this phase of the scriptwriting decided to let the protagonists be academics.

But into the plot about stealing scientific results is intermingled a secondary

political plot about press censorship in a dictatorship somewhere in Europe. In

this version, Arne is a political figure who for several years has been

suspected by the government of working in the country’s freedom movement.

Actually, the Arne in the synopsis is an even more political figure than Gustav

in Somin’s play, since it is often mentioned how inspired the youth is by his

ideal of freedom (7). Further, we are told that

The first page of Dreyer’s “politically toned” synopsis. Found in the Swedish Film

Institute’s Library.

Det der havde pint ham saa meget i Aarene efter at han var vendt hjem fra det udenlandske Universitet, var det at se, hvor hans Landsmænd havde været Slaver—af Angst. Næsten ingen havde turdet lytte til Beretningerne udefra. Der, hvor Arne havde studeret, var Sandheden noget man kunde tvivle om eller diskutere, - men hjemme havde Sandheden været noget indiskutabelt, noget absolut, som alle troede paa, selvom de inderst inde vidste det Hele var Løgn. (4)

Dreyer here heightens the political dimension even more than Somin does. In the synopsis, Sander is a scientist working within and thus—in reality—for the merciless dictatorship, and he is demonized further by having been the cause of two attempted suicides by a young female laboratory technician.[It had tormented him so much in the years after he had returned from a foreign university to see how his countrymen had become slaves—of fear. Almost no one had dared to listen to reports from outside. Where Arne had studied, the truth was something that you could doubt or discuss—but here at home the truth could not be discussed, it was something absolute, that everybody believed in, even though they knew deep down it was all a lie.]

Some of the elements that Dreyer ends up adding in the film are already to be

found in the synopsis, but here they are given a political inflection: When the

couple are dancing together, they start to sing along to the freedom movement’s

national anthem played on the illegal radio (5), and just

before they expire as a result of the poison they have taken (Dreyer already had

that idea here), Liesa thinks that she in the distance can hear a male voice

singing freedom songs, while “police officers with machine guns” (12) are about to

storm their apartment:

“Frihedssangen er det sidste, Liesa hører, hun smiler

svagt. Saa dør hun.” [Freedom is the last word, Liesa hears, and she smiles weakly.

Then she dies.] (12)

During the transformative process from drama to film, Dreyer’s intention has

obviously been to stay quite loyal to the political dimension of his source, but

eventually he chose to make a pure, melodramatic chamber drama. Perhaps the

decision to eliminate the political can chiefly be attributed to Dreyer’s

aesthetic preoccupations. But another explanation could be that a political

allegory about fascist dictatorships could have created difficulties for him,

even in neutral Sweden—after all the war hadn’t ended yet when the film was

produced in the summer of 1944. And not every Swede was hostile to Hitler.

Indeed Swedish companies continued to do business with Germany during the war.

It is important to stress, though, that this possible explanation is never

mentioned in the existing sources. It seems as if Dreyer definitely could have

made a political film if he wanted to, for he was not under any kind of pressure

from the producers when it came to the content of the film. The reasons for his

disowning of the film were the choice of actors, the adding of melodramatic

music, and the final editing (that he was not allowed to do himself).

It is also worth mentioning that the major Swedish director in the 1940s, Gustaf

Molander, made at least one political film in this period, Der brinner en

eld [There Burned a Flame] (1943). Molander also made other serious

films in this period, among them the first adaptation of Kaj Munk’s

Ordet (1943)—although we are more familiar with the later

Dreyer version from 1955. But even though Two People is a serious

drama with a political source Dreyer doesn’t at all seem to be influenced by

thematic trends or aesthetic currents in Swedish film in this period. Whenever

he was asked in interviews about Swedish films he always chose to mention only

the two major figures of the silent period as inspirations, Mauritz Stiller and

Victor Sjöström, especially the latter.

The self-sacrificing woman with a strong will

In both film and play the female lead can be seen as a self-sacrificing woman to

whom love without compromise is a crucial value. An important indication of this

can be found in the dialogue and action set out for Liesa in the following

passage: “(kneeling in front of him, and taking his hand): Gustav, I’ll go

anywhere, if it’s to help you” (242). The humble

kneeling in front of her husband has also found its way into the film, although

it here appears somewhat later. An expression of her complete self-sacrifice

that occurs only in the film is Marianne’s tearful utterance just before the

couple die: “Det jag vill säga dig kan sägas med ett enda

ord—tack [What I want to say to you, can be said with just one

word—thanks!]”.

However, Dreyer’s female protagonist does indeed appear stronger and

psychologically more complex than Somin’s. Like the heroines in a number of

Dreyer’s other films— Master of the House (1925), The

Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Day of Wrath (1943),

and Gertrud (1964)—in Marianne the self-sacrificing attitude is

combined with a strong will and a high degree of intransigence in love matters.

The following line from Marianne, just before she dies, is exclusively to be

found in the film, and it seems to point towards Dreyer’s famous Gertrud-figure,

created more than fifteen years later: “Jeg vil hellere dø end at leve

uden at elske. [I would rather die than live without loving.]” In this

context there are three other interesting differences between the portraits of

the female protagonist in respectively the film and its source:

1) In the play Liesa has had an affair with Sander while married to Gustav (she

couldn’t resist Sander’s charm). In the film the affair—as analogously in

Verneuil’s play—took place in her youth a couple of years before she met her

husband. In that way Marianne appears to be more pure in her love—her mistake is

seen as a result of youthful inexperience which an older, cynical man took

advantage of.

2) It is true that Dreyer let Marianne kneel in front of Arne, but at the end of

the film the opposite situation actually occurs, when Arne finds out what

sacrifice Marianne has made. The self-sacrificing love goes both ways, and it is

the man who at the end must admire the woman’s ability to love without

compromise. The kneeling man is not to be found in the play, indeed it would be

extremely difficult to imagine the worker Gustav performing such an act. Since

the double suicide takes place offstage in the play we do not witness the fatal

act itself. In Dreyer’s film, on the other hand, we see Arne finding comfort in

Marianne by laying his head on her lap just before they die together. Again,

the typical Dreyer woman appears to be strongest in the most decisive and fatal

moments.

3) In the film it is Marianne who makes the decision that they should commit

suicide by taking poison. In the play Gustav—in accordance with more traditional

gender roles—is the one who makes the decision and performs the deed (he shoots

her, then himself). In this connection it is interesting and understandable that

Dreyer has not included Somin’s strange and ambiguous conclusion when the radio

announces that the married couple’s suicide wasn’t necessary, because another

suspect has emerged. Somin’s point was probably that personal guilt is more

important than society’s judgement, and suicide is therefore necessary, whether

the justice system acquits one or not. Such an ending didn’t interest Dreyer;

instead he wanted to pay tribute to Arne and Marianne’s idealistic love, and he

therefore lets church bells ring, while the poison spreads

through the couple’s bodies. It is an open question in the film whether the

church bells are real or just a product of Arne’s inner ear before he dies. When

Marianne says that she can hear the bells too, she could be pretending, because

she wants to comfort her husband in their final hour.

Although Dreyer seems to have been fascinated by Somin’s Liesa, it is

clear that he has decided to change a lot about her character in the

transformation from drama to film. Besides her name he has changed her

social status, and he has made her stronger, more innocent and definitely more

pure. In many ways, Marianne seems to have more in common with Dreyer heroines

like Anne Pedersdotter in Day of Wrath (1943), Jeanne d’Arc in

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and Gertrud in

Gertrud (1964) than with Somin’s Liesa. The Dreyer heroine often suffers because of male

repression, but she is always proud and never

afraid of taking the initiative.

Narrative and factual analysis

Even though Dreyer accords himself a certain amount of freedom in recasting the

themes of his source, he chooses to follow its narrative line rather faithfully.

Somin’s play is structured like a classical naturalistic chamber drama, divided

into three acts of roughly equal length, and the unities of the classical drama

are almost completely respected. An exception, though, is the unity of place,

since this changes between the first and the second acts, where the action is

moved to the “BERGMANN’S new flat in a modern block of workers’

dwellings” (257). The apartment has been made

available to the couple because of Gustav’s political efforts in the opposition

party. There is no indication of how long a time is supposed to have elapsed

between the two acts, but probably only a few weeks since we are told that mess

and packing cases should be part of the set design.

Surprisingly enough, Dreyer chooses in his adaptation to be more faithful to the

three classical unities than his dramatic source was. The whole movie takes

place in the same apartment in the course of a single day, from late afternoon

to early evening. In this way he increases the focus on the intense

psychological drama. When it comes to the structure and the basic elements of

the crime plot, Dreyer is largely true to his source. The most important events

in the play are given the same status and narrative weight in the film (the

murder of Sander; Liesa/Marianne’s confession; the double suicide). Furthermore

small but important items such as the murder weapon (a Mauser pistol) and the

missing glove at the scene of the crime are also loyally carried over by the

Danish director. A small but significant difference is the position of the

climax, which in both film and drama may be said to be Liesa/Marianne’s

confession of her relationship with and murder of Sander. In the play it is not

until the very end that this secret is revealed (296, 9/10s of the

way through the text).

The effect of this placement of the climax is to focus the action on the crime

plot. That we as readers—as a result of Liesa’s many, very obvious hints and

desperate remarks—have figured out the truth several pages earlier is simply one

of the play’s aesthetic shortcomings. In Two People it’s exactly

halfway through the movie that Marianne tells Arne about her affair with Sander,

and after that it takes not less than eleven minutes (exactly 2/3s of the way

through the movie) before she confesses the murder. By stretching and dividing

the confession Dreyer makes sure that the main focus is on the emotional

conflict instead of the crime plot.

Where Dreyer—in comparison with his source—really adds something is in his use

of leitmotifs and his creation of a symbolic setup-payoff effect. The Italian

lullaby Bella Mama is a musical leitmotif that Marianne sings twice

during the movie. It appears as a double symbol because it represents both the

innocent candour that characterizes Arne and Marianne’s love for each other, and

their longing to achieve an harmonious marriage with children. Marianne sings it

to her husband almost halfway through the film just before she confesses to him

that she dreams about having a child. The second time she sings it for Arne is

just before the couple die in each other’s arms. Arne is seen here lying with

his head in her lap, he is—like a modern Oedipus—transformed into the son she

will never have.

In the film Dreyer uses a short poem by Bo Bergmann to create a symbolic

setup-payoff effect. Arne and Marianne analyze it together approximately midway

through the film, and its content gives us a hint of the tragic ending that will

come to their tender relationship: “Klara skola människornas ögan vara/

Stilla skola de lysa i lyckans lille korta minut/ innan lycken är

borta. [Clear should the eyes of the human being be/ Quietly should they

light up in happiness for a minute/ before the happiness is

gone.]” Reading Dreyer’s script for the film, we realize that

his first plan was to use three verses from a poem by Danish writer Ludvig

Holstein: “Hun har stora nervösa ögan,/ hon liknar en rå som flyr/

Hon är alltid rädd för något/ och ved ej själv vad hon skyr” [She has big nervous

eyes,/ she looks like an escaping roe,/ She’s

always afraid of something/ but does not know what it

is] (65). The choice of these latter lines

was obviously not determined by a desire to create a setup effect; rather they

would have functioned as a device signaling Marianne’s inner emotional chaos in

the face of the murder.

As far as factual elements are concerned, Dreyer has, as already mentioned,

changed a lot. Gustav and Liesa Bergmann are in the film called Arne and

Marianne, and the former is no longer a working class rebel, but a scientist.

The demonic Sander has been allowed to keep his name, but he has been

transformed from a politician into a scientist. The changes of occupation and

environment have consequences for the transformation of the lines. The rawer and

more straightforward language of Somin’s play has been replaced in Dreyer’s film

by language that is more emotive and artificial. For example, it is impossible

to imagine Dreyer trying to incorporate the following line by Gustav into his

film:

He [Sander] should have been torn limb from limb; his eyes should have been gouged out, his tongue should have been put like a squirrel in a drum, to run and run until he spat out his lungs bit by bit, and his heart burst through his currants [sic]. The fiend! (298)

Dreyer stays true to some of the emotional declarations of love in his original,

and also to some of the lines that have to do with the crime plot. Yet we must

acknowledge that he significantly changes the language of the play. Another

basic element he changes is the place of the action: Somin’s play is supposed to

take place in Germany in the 1930s, while Two People seems to

take place in Sweden of the 1940s, if the newspaper headlines, the radio news,

the Swedish poems are taken into consideration.

From working class drama to academic showdown

The conclusion must be that with his film Two People Dreyer

didn’t make it a priority to remain true to Somin’s play Close

Quarters. On a thematic level he chooses to change a political

working class drama into a passionate and emotional showdown between academics.

The strength of women in love matters is also far more important to him than it

is to Somin. Dreyer largely reproduces the basic narrative structure of the play

(the order and hierarchy of the events); clearly the crime plot doesn’t interest

him very much—it’s only supposed to be used as background for the emotional

drama. As regards the identities of person and place he has changed almost

everything.

In short this film was produced at a time in Dreyer’s career when he wanted to

distance himself from the literary sources he used. Two People is

the last film he directed before he again chose to focus primarily on sources

written by established and recognized writers. In this connection it is still

important to remember that Dreyer was less interested in Somin’s play than in

the issues it raised; certainly he was very aware of its weaknesses.

On a more general level, the comparative analysis has shown us that we have to

look at authorship in film in a more complex way than we normally do—and

especially how it was regarded among the French directors of the Nouvelle Vague

in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It is too simple just to divide film

directors into two categories: the loyal adaptors and the auteurs who only use

literary sources as a stepping stone to follow their own visions and ideas.

Throughout his directing career Dreyer shows us a third way: it is possible to

be a loyal interpreter and an innovative artist at the same time—a way of

approaching the business of adaptation that can also be found in the works of

great film directors such as F. W. Murnau, Luchino Visconti, Akira Kurosawa, Jan

Troell, and the Coen Brothers (e.g. No Country for Old Men

[2007]).

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the help of Magnus Rosborn, assistant at the Swedish Film

Institute’s Library, in finding material used in this article. This article could

not have been written without the benefit of the Dreyer Archive in the Danish Film

Institute (DFI), Copenhagen.

NOTES

- The article appeared for the first time on New Year’s Day, 1922, in the Danish newspaper Politiken.

- This was also criticised by some contemporary critics, among them the reviewer of Aftonbladet, March, 24, 1945, who pointed out that “Människouppfatningen är … den på scenen traditionella, tilrättalagda [The treatment of the script is … the theatrical, traditional one]”. Unless otherwise indicated all translations are my own.

- Monsieur Lamberthier was first performed in Paris in 1927. In 1929 it was translated by Holger Bech for internal use by The Danish Royal Theatre, and printed by Carl Strakosch A/S, Dahlerupsgade 5, Copenhagen. A copy of this text is preserved in The Royal Library, Copenhagen.

- Luft 194. According to (Drouzy vol. II 176) Dreyer was already in 1933 working on a screenplay based on Verneuil’s play.

- A film adaptation had already been made in 1929 titled Jealousy. As in the 1946 version the cast was also enlarged in this one

- Dreyer’s sixth feature, the silent, German adaptation of Danish writer Herman Bang’s novel Mikaël (1904, filmed for UFA in 1924) is actually often referred to as the first example of that particular genre (Schrader 115).

- This is what it is called in the published English edition; thus it isn’t just a translation of the unpublished German version.

- Found in R.XVIIISF in the Library at the Swedish Film Institute.

- Quoted in Olsson 1983 177.

- An example can be found in Drum and Drum (84).

- In the early synopsis with its political stress, the female protagonist appears even more pure, since her relationship with Sander hasn’t been a sexual one—they have just flirted together a couple of times.

REFERENCES

- Anon. 1945 March 24.

Review of Två Människor.

Aftonbladet. - Dreyer, Carl Th. 1964.

Nye Ideer i Filmen.

Om Filmen. Copenhagen: Gyldendals Uglebøger. - ⸻. 1973.

New Ideas About the Film.

Dreyer in Double Reflection. Trans. Donald Skoller. New York: Dutton. - Drouzy, Martin. 1982. Carl Th. Dreyer—født Nilsson, I-II. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Drum, Jean, and Dale D. Drum. 2000. My Only Great Passion. The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer. Landham, Maryland London: The Scarecrow Press.

- Egholm, Morten. 2009. En visionær fortolker af andres tanker Om Carl Th. Dreyers brug af litterære forlæg. Unpublished Ph.d.-dissertation, KUA, University of Copenhagen.

- Kau, Edvin. 1989. Dreyers filmkunst. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

- Luft, Herbert. 1956.

Carl Dreyer—A Master of His Craft.

Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television 11 (2): 181-96. - Michaelis, Cassie, Heinz Michaelis, and W. O. Somin. 1934. Der braune Hass. La Haine brune. The Brown Hate. Saint Gall (Suisse): Impr. Volkstimme; Paris: Librairie Lipschutz (4, place de l’Odeon).

- Neergaard, Ebbe. 1963. Ebbe Neergaards Bog om Dreyer i videreført og forøget udgave ved Beate Neergaard og Vibeke Steinthal. Copenhagen: Dansk Videnskabs Forlag.

- Olsson, Jan. 1983.

Carl Th. Dreyers Två Människor.

Sekvens, Filmvidenskabelig årbog 6: 165-182. - ⸻. 2005.

Två Människor/Two People.

The Cinema of Scandinavia. Ed. Tytti Soila and Jacob Neiiendam. London: Wallflower. 79-91. - Schrader, Paul. 1988. Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. New York: Da Capo Press.

- Somin, W. O., Cassie Michaelis, and Heinz Michaelis. 1934. Die Braune Kultur. Ein Dokumentenspiegel. Zürich: Europa-Verlag.

- Somin, W.O. 1935.

Close Quarters.

Famous Plays of 1935. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. - Verneuil, Louis. 1929. Monsieur Lamberthier. Trans. Holger Bech. Copenhagen: printed for The Danish Royal Theatre by Carl Strakosch A/S, Dahlerupsgade 5.