SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 19 (2010) pp.56-71.

Title: Op med hodet: Tancred Ibsen’s 1933 Experiment in Cinematic Modernism

Author: Arne Lunde

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Statement of responsibility:

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal

Source(s): Lunde, Arne. 2010.

Op med hodet: Tancred Ibsen’s 1933 Experiment in Cinematic Modernism.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 19: 56-71.

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- cinema and psychology

- cinema and religion

- cinematic expressionism

- cinematic hybridity

- cinematic modernism

- experimental film

- Ibsen, Tancred

- Norwegian cinema

- Op med hodet [Cheer Up!]

- MDH: started markup 10th May 2010

- MDH: entered author's proofing corrections 31st August 2010

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 15th November 2010

- MDH: added page numbers from print journal edition 11th April 2012

Op med hodet: Tancred Ibsen’s 1933 Experiment in Cinematic Modernism

Arne Lunde

ABSTRACT: The grandson of two of Norway’s most famous nineteenth-century writers,

Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Tancred Ibsen holds a central place in the

history of Norwegian cinema. He was its leading director in the 1930s and 1940s and

is best remembered for Den store barnedåpen [The Great Baptism] (1931), Fant [Tramp] (1937) and Gjest Baardsen (1939). Ibsen’s third feature film, Op med hodet [Cheer Up!], from 1933, has meanwhile remained largely forgotten and unseen outside

of film archives.

Ibsen later wrote in his autobiography that, regarding his own development, no film

had meant as much to him or taught him as much. With Op med hodet, Ibsen self-consciously borrowed from the polar opposite worlds of the Hollywood

popular-genre film and the European avant-garde cinema. Despite the film’s commercial

failure and relative obscurity to date, Op med hodet reveals Tancred Ibsen as a modernist European filmmaker and artist attempting technical

and narrative experiments radical for their time in Nordic cinema.

RÉSUMÉ: Tancred Ibsen, petit-fils de deux des écrivains norvégiens du dix-neuvième

siècle les plus connus, Henrik Ibsen et Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, occupe une place centrale

dans l’histoire du cinéma norvégien. Il en était le réalisateur principal dans les

années 1930 et est plus connu pour ses films Den store barnedåpen [The Great Baptism], Fant [Tramp] et Gjest Baardsen (1939). Le troisième film d’Ibsen, Op med hodet [Cheer Up!], de 1933, est longtemps demeuré oublié et méconnu en dehors des archives.

Ibsen écrivit

plus tard qu’aucun film n’avait eu autant d’importance et ne lui avait autant appris.

Avec Op med hodet, Ibsen a consciemment emprunté aux mondes diamétralement opposés du genre populaire

d’Hollywood et du cinéma avant-gardiste européen. Malgré l’échec commercial du film

et son manque de popularité, Op med hodet nous révèle Tancred Ibsen comme étant un cinéaste européen moderniste et un artiste

nordique dont les expériences techniques et narratives sont en avance sur leur temps.

Tancred Ibsen holds a central place in the history of Norwegian cinema and was its

leading director in the 1930s and 1940s. Working in genres as diverse as musicals,

documentaries, screwball comedies, historical adventures, psychological crime thrillers,

and literary adaptations, he made twenty-three feature films between 1931 and 1963.

Ibsen was the grandson of two of Norway’s most famous nineteenth-century writers,

Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. His best-known films include the first Norwegian

sound film, Den store barnedåpen [The Great Baptism] (1931), as well as two classic features starring Alfred Maurstad:

Fant [Tramp] (1937) and Gjest Baardsen (1939). These two latter films are at the centre of the Tancred Ibsen oeuvre and

are considered the key works from Norwegian cinema’s very brief gullalder [golden age] which lasted from 1937 until the German Occupation began in 1940 (Iversen

34-52).

By comparison, Tancred Ibsen’s third feature film, Op med hodet [Cheer Up!] 1933, has remained largely forgotten, and unseen outside of film archives.

Yet Ibsen

himself later wrote that regarding his own development, no film had meant as much

to him or taught him as much as Op med hodet. As a largely modernist, avant-garde work, the film has no peer in the history of

early Norwegian cinema. Perhaps no other Norwegian feature fiction film attempted

anything as freewheelingly ambitious in its narrative and structure until Erik Løchen’s

1959 New Wave classic Jakten [The Hunt].

With Op med hodet, Ibsen self-consciously borrowed from the polar opposite worlds of the Hollywood

popular-genre film and the European avant-garde cinema. At the same time, he foregrounded

his own pioneering visual-aural collages, narrative constructions, and autobiographical

self-expressionism. Despite the film’s commercial failure and relative obscurity

to date, Op med hodet reveals Tancred Ibsen as a modernist European filmmaker and artist attempting technical

and narrative experiments often radical for their time.

In the present study, I will first examine how Ibsen’s film self-consciously calls

attention to its own form through narrative framing and structural fragmentation,

deliberately foregrounding its own artificiality. Secondly, I will focus on how Op med hodet autobiographically explores Tancred Ibsen’s own self-identity dilemmas vis-à-vis

his famous family. I shall discuss how the film is inspired by the twin currents of

American and European cinema from the decade that preceded it. And finally, I will

demonstrate how as a modernist work, Op med hodet explores visual and aural means of representing subjectivity and inner states of

consciousness, as well as dislocation and alienation.

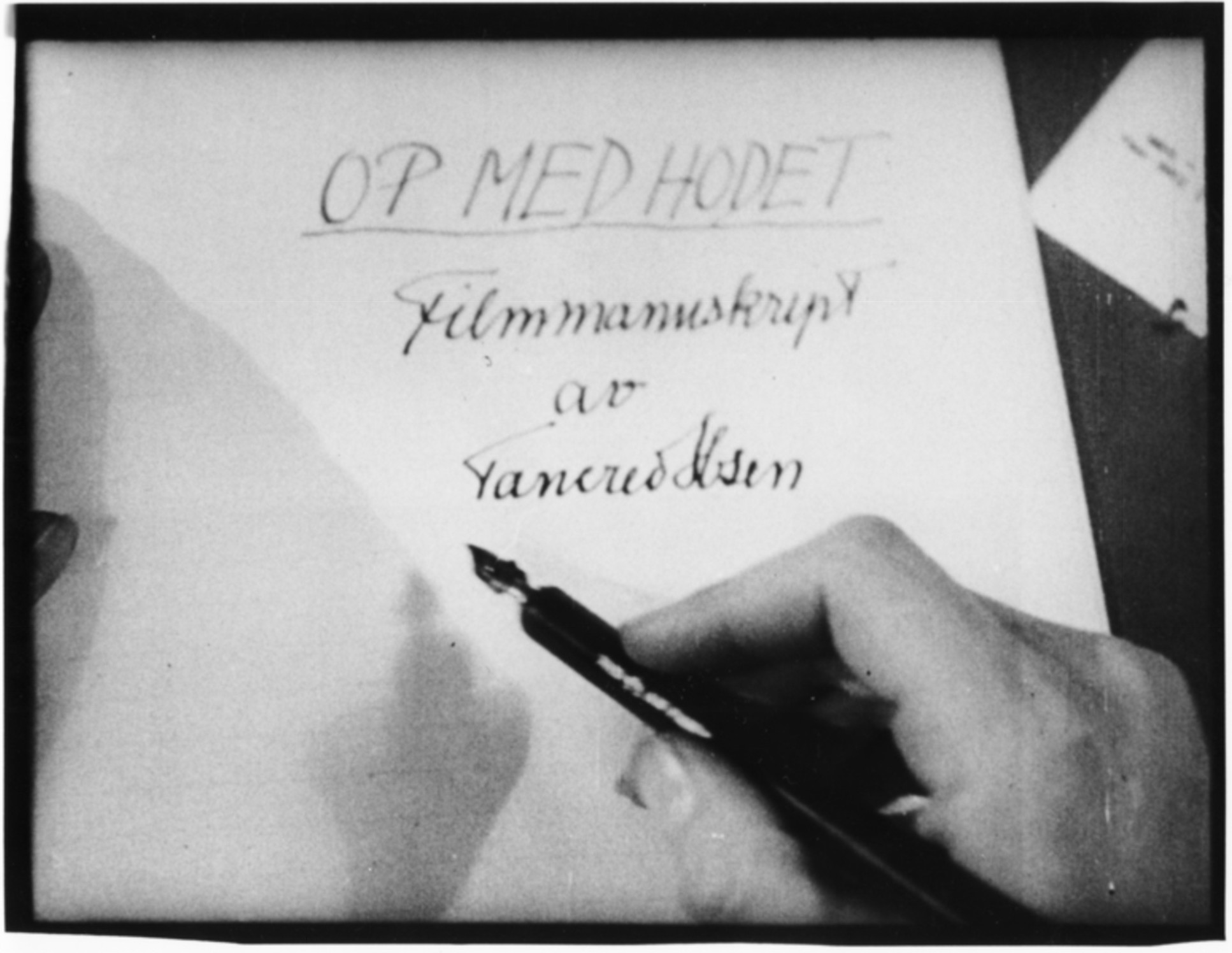

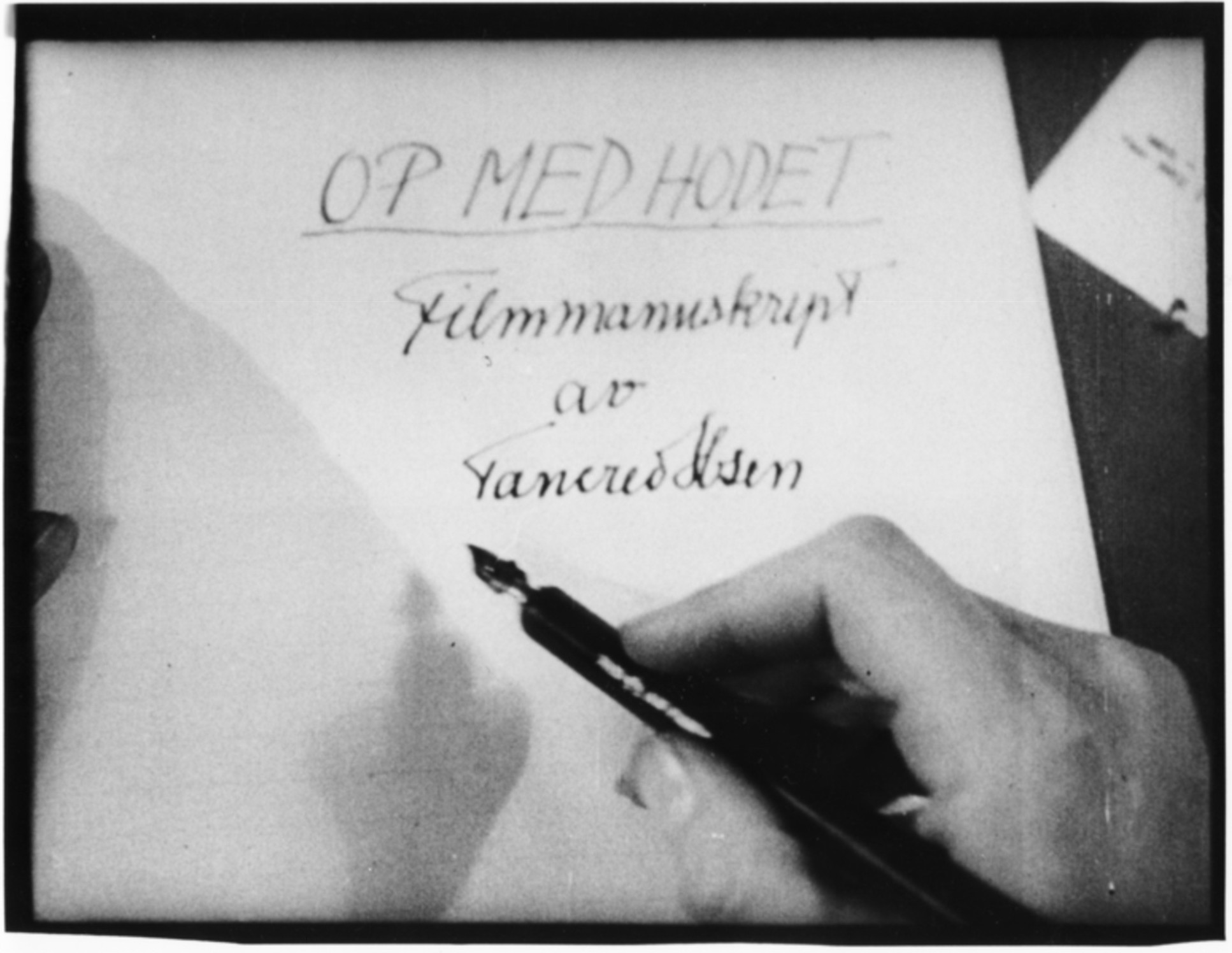

Op med hodet immediately posits its modernist self-consciousness through its own beginning title

credits. The camera reveals a close-up of a blank manuscript page (Figure 1). Holding

a fountain pen, Ibsen’s own hand begins to write two pages of introductory credits

while the jazz score on the soundtrack plays the title melody.

Briskly handwriting the credits in real-time, Ibsen signals to the spectator

that the film is an “authored” work, as legitimate a creation of personal authorship

as a novel or a play. Tancred

Ibsen’s deliberate choices here of the fountain pen, the blank manuscript page, and

the written word, self-consciously connect Op med hodet to his grandfathers’ literary works and their posthumous reputations.

Briskly handwriting the credits in real-time, Ibsen signals to the spectator

that the film is an “authored” work, as legitimate a creation of personal authorship

as a novel or a play. Tancred

Ibsen’s deliberate choices here of the fountain pen, the blank manuscript page, and

the written word, self-consciously connect Op med hodet to his grandfathers’ literary works and their posthumous reputations.

Figure 1

Ibsen further explores this ancestral theme in a later sequence, perhaps the film’s

most surrealistic. His comic protagonist, Theobald Tordenstam, a would-be Shakespearean

actor with a nervous speech stammer, has just been humiliatingly rejected by the National

Theatre in Oslo. As Theobald leaves the theatre in defeat, he passes between the

two famous pillared statues of Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson standing guard

out front. In succession, both stationary statues briefly come to life, turn, and

address the young man directly. The Henrik Ibsen statue sweeps its hand while saying

“Gå utenom” [Go round about], which is the Boyg’s advice to Peer Gynt in Act II, Scene

VII of Ibsen’s verse-play

(Figure 2).

By comparison, the Bjørnson statue (FIgure 3), with an upward sweep of its

arm instructs Theobald to: “Løft ditt hode, du raske gutt!” [Lift your head, you restless

youth!], the opening line of a poem from Bjørnson’s novel En glad gutt [A Happy Boy].

Theobald, as the only witness to these metamorphoses, looks bewildered and stunned.

Theobald, as the only witness to these metamorphoses, looks bewildered and stunned.

Figure 2

Figure 3

This statues-coming-to-life sequence has a hallucinatory quality bordering on magical

realism. The episode is filled with autobiographical nuances as well. Because Tancred

Ibsen himself achieved his first fame at birth as the celebrated “dobbeltbarnebarn”

(double grandson) of Ibsen and Bjørnson, he grew up in the dual shadow of his famous

grandfathers and the expectations such a genetic inheritance placed upon him. In

addition, his father Sigurd Ibsen’s fame as one of Norway’s most illustrious diplomats

and his wife Lillebil’s international celebrity as a ballet dancer also contributed

to Tancred’s “complex” as the underachieving Ibsen in the family. The National Theater

sequence with Theobald

autobiographically echoes Ibsen’s own serious artistic ambitions and self-doubts,

his previous rejections and failures, as well as the larger-than-life “ghosts” of

his grandfathers’ reputations.

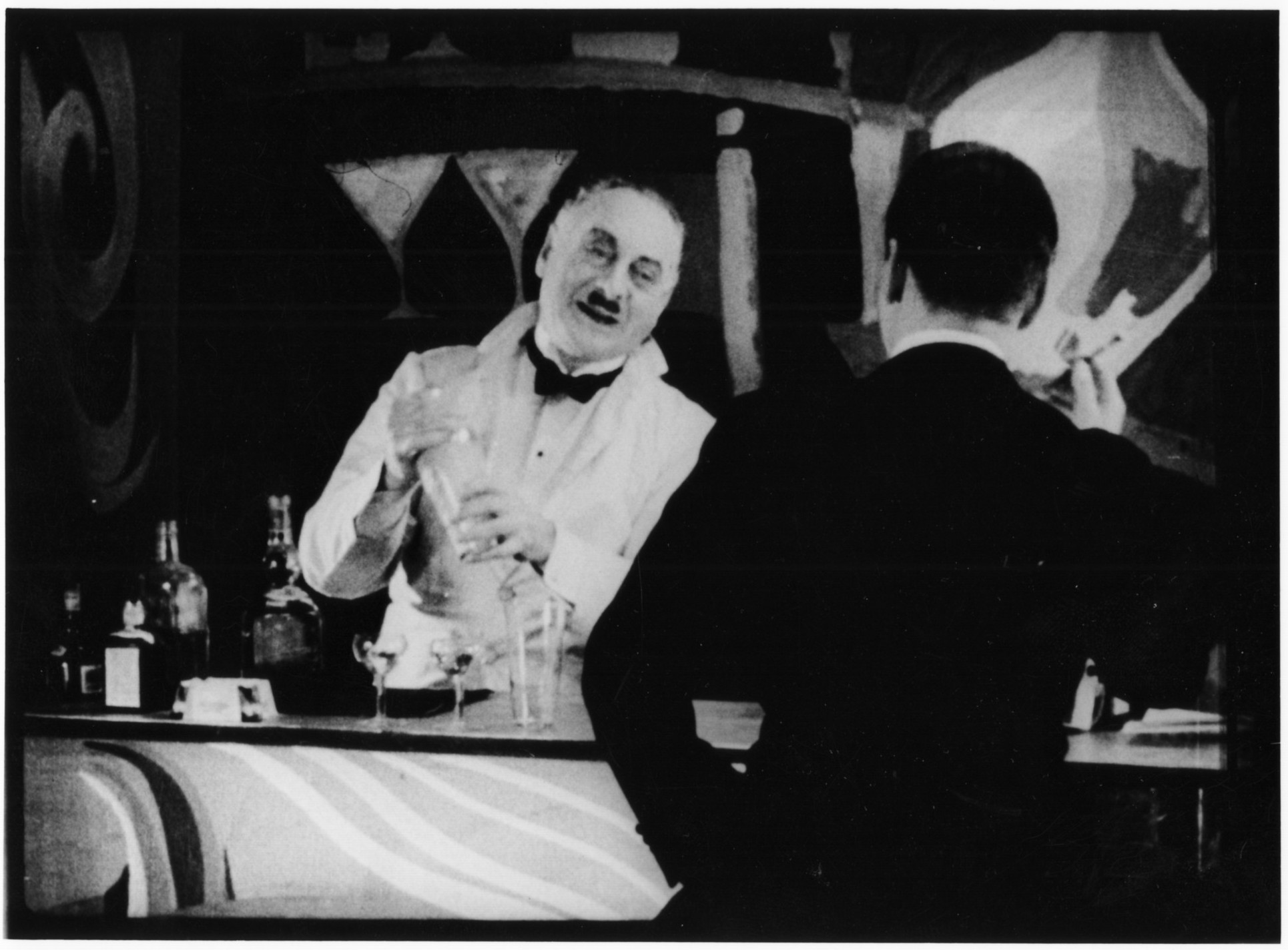

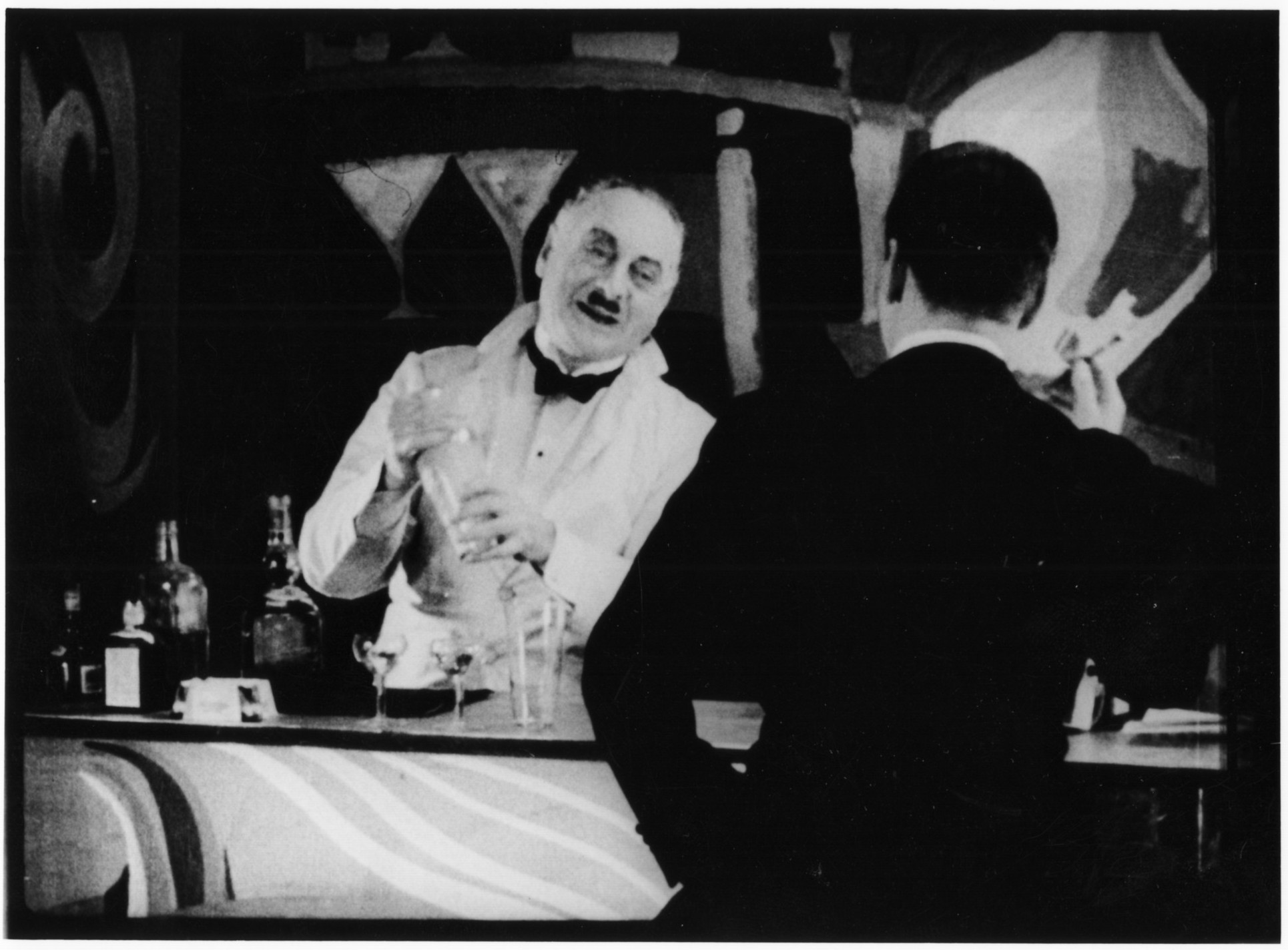

The self-reflexively modernist experimentation which Ibsen initiated with the handwritten

opening credits is further developed through an even more unconventional credits sequence.

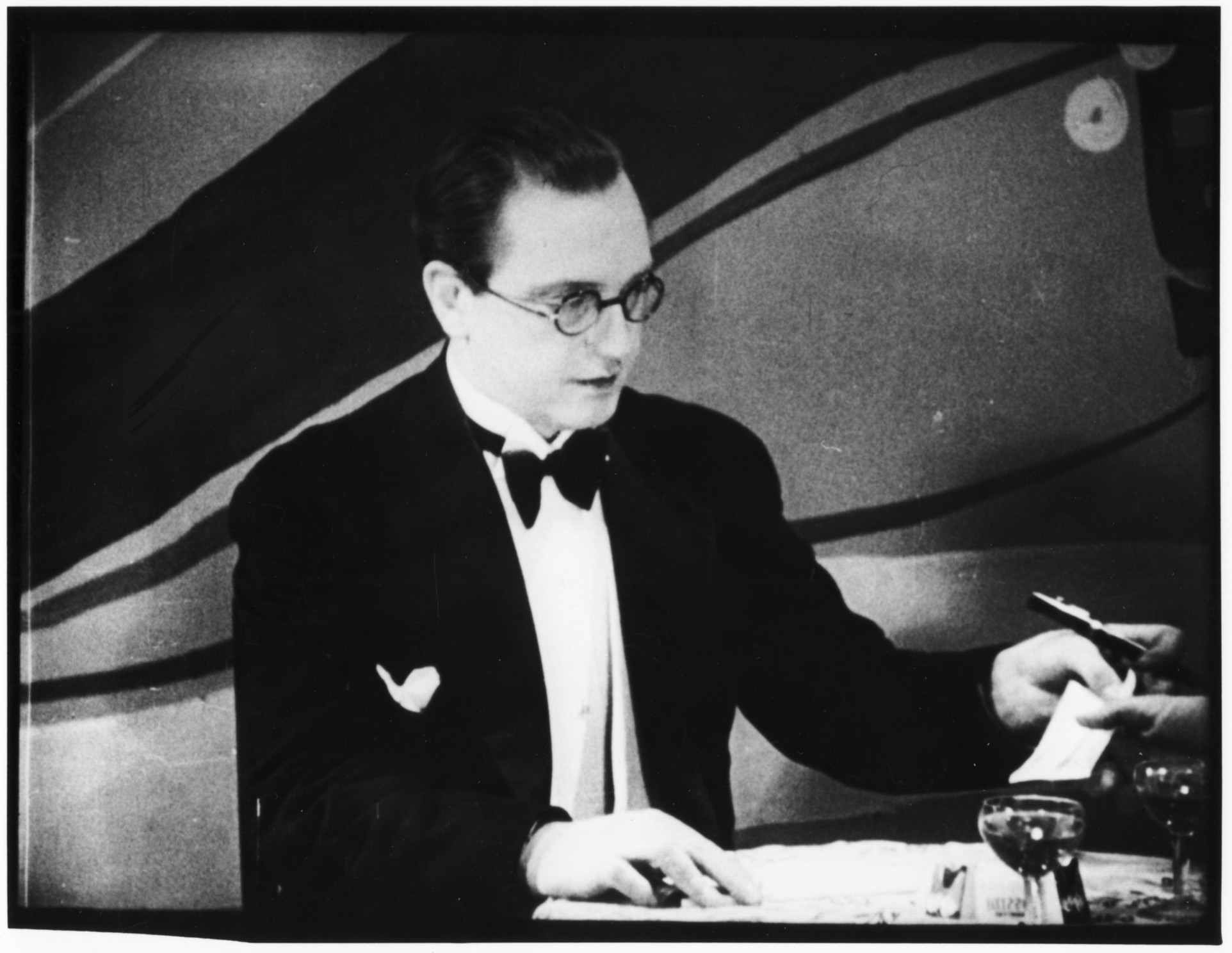

Inside an expressionistically-painted nightclub interior, a tuxedoed patron asks a

bartender to recommend a drink (Figure 4).

The drink-concoction which the bartender begins to describe and simultaneously

mix turns out to be a metaphor for the film itself. “Op med hodet er en cocktail av musikk, humor og sjarm” [Op med hodet is a cocktail of music, humour and charm] he intones. This bartender-narrator then

continues the interrupted introduction

of the film’s opening credits through visual and aural means (close-ups and voice-overs)

instead of through the usual texted credits.

The drink-concoction which the bartender begins to describe and simultaneously

mix turns out to be a metaphor for the film itself. “Op med hodet er en cocktail av musikk, humor og sjarm” [Op med hodet is a cocktail of music, humour and charm] he intones. This bartender-narrator then

continues the interrupted introduction

of the film’s opening credits through visual and aural means (close-ups and voice-overs)

instead of through the usual texted credits.

Figure 4

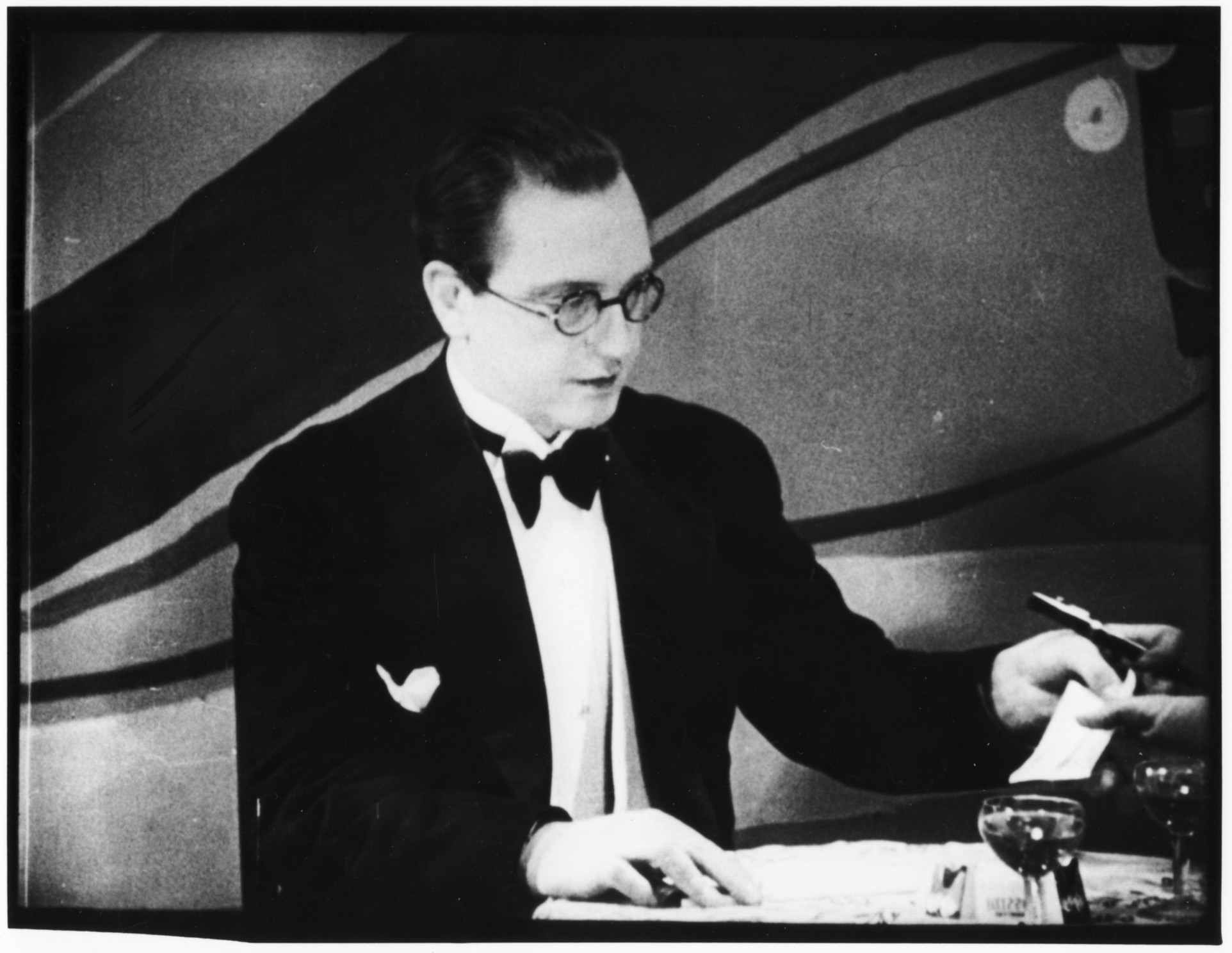

Matching the bartender’s witty, free-verse introductions on the soundtrack, the camera

cuts to a close-up of the film’s actual co-producer, Erling Bergendahl, sitting at

a table while writing checks;

followed by a shot of the film’s sound-engineer, Carl Halling, wearing headphones

and standing amid his recording equipment (Figure 5);

and finally by a profile shot of the cinematographer, Harald Berglund, who

suddenly begins to handcrank his camera after tilting it toward the spectator (Figure

6). These visualized and voice-overed credits of behind-the-scenes collaborators seem

radical for their time. Ibsen’s inventiveness here anticipates the end credits of

Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) in which both of these later films credited the main technical crew through

voice-overs and visuals only. Ibsen had experimented with the idea in 1933.

followed by a shot of the film’s sound-engineer, Carl Halling, wearing headphones

and standing amid his recording equipment (Figure 5);

and finally by a profile shot of the cinematographer, Harald Berglund, who

suddenly begins to handcrank his camera after tilting it toward the spectator (Figure

6). These visualized and voice-overed credits of behind-the-scenes collaborators seem

radical for their time. Ibsen’s inventiveness here anticipates the end credits of

Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) in which both of these later films credited the main technical crew through

voice-overs and visuals only. Ibsen had experimented with the idea in 1933.

Figure 5

Ibsen’s bartender-narrator continues to introduce the cast of onstage and backstage

collaborators, including the film’s composer, orchestra leader, musicians, variety

solo performers, and leading and supporting players, as well as shots of lighting

equipment and set designs. All are ingredients in the bartender’s cocktail, “Op med

hodet,” which this narrator shakes,

pours and serves to the faceless patron at the bar (who stands in for the film

audience). Through this radical opening credit sequence, Ibsen calls attention to

his work as a construction and foregrounds the artificiality of the subsequent diegesis.

This self-reflexive problematization of narrative form is one of the characteristics

of literary modernism in the early twentieth century.

Figure 6

Although the film’s subsequent main plotline to a large extent appropriates formulaic

popular genres familiar to his audience, Ibsen’s avant-garde narrative constructions

and techniques consistently work against these formulas and genre expectations. Op med hodet has a split identity as a self-consciously modernist European film in constant dialogue

with popular-genre American cinema. Ibsen borrows from the European avant-garde cinema

of the 1920s and early 1930s, as well as from Hollywood formulas and personae from

the same period, while integrating into this new hybrid revealing autobiographical

elements, touches of magical realism, and modernist cinematic expressionism.

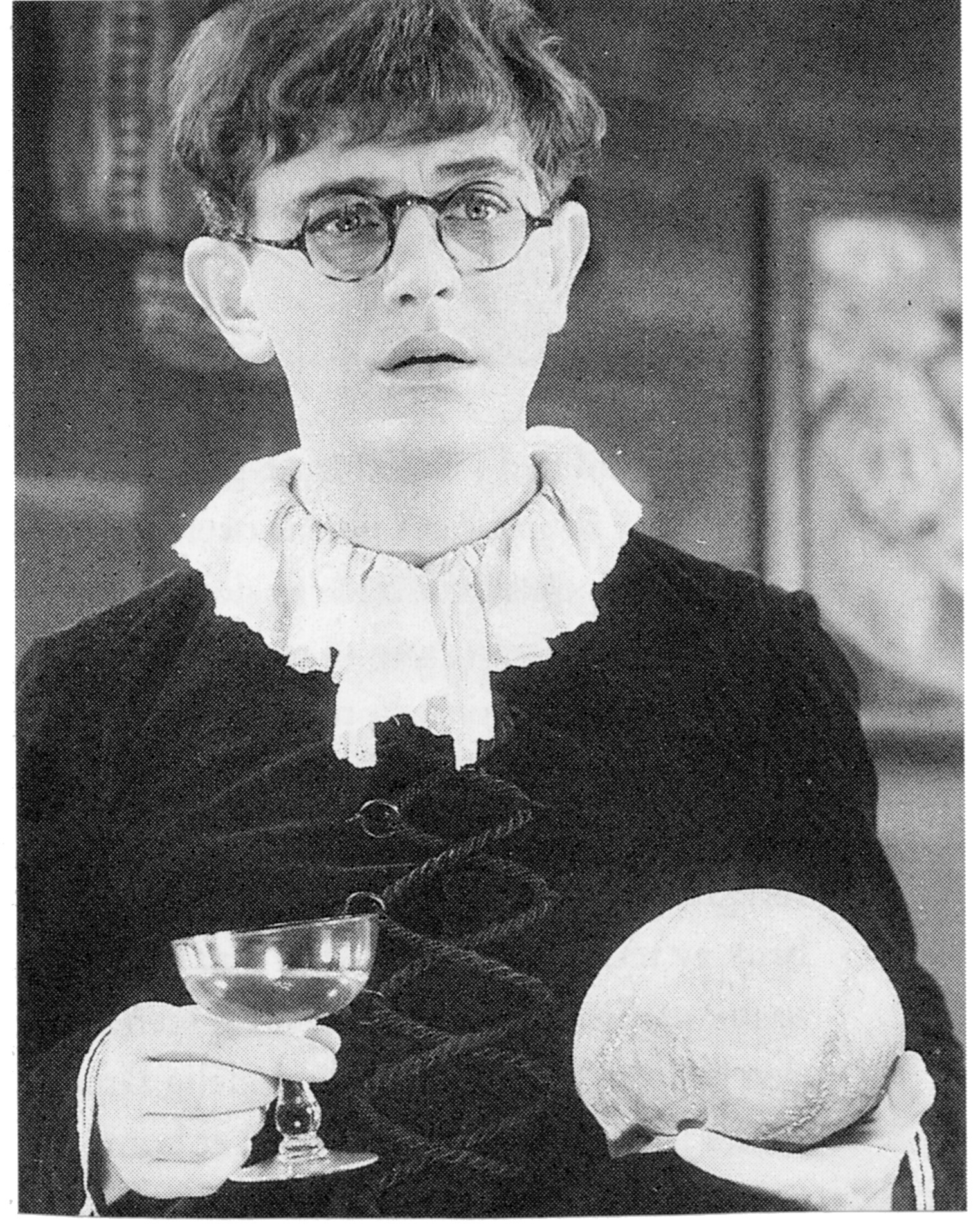

In creating Theobald Tordenstam as a rural innocent with a severe stutter and paralyzing

stage fright, who nonetheless burns to be a serious Shakespearean actor, Ibsen appropriated

essential elements from Harold Lloyd’s American comic screen persona. LLoyd surpassed

even Chaplin and Keaton in total box-office revenues in both the U.S. and

Europe during the latter half of the 1920s. He specialized in naive, bespectacled

overachievers whose optimism and energy triumphed in the end, but only after public

humiliations and harrowing physical trials. Theobald Tordenstam’s horn-rimmed glasses,

small-town roots, social ineptitude, first-love rapture, and masochistic tenacity

essentially mirror the Harold Lloyd prototype (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Ibsen was also undoubtedly quite conscious of the Hollywood backstage musical and

all-star-revue film genres that proliferated during the early talkie period and were

exported globally. He very likely had these models in mind when in 1931 he first seized

on the idea of creating a film about the making of a musical revue stage production

by incorporating Oslo’s celebrated Chat Noir theatre and its company of performers,

musicians, and technicians (Ibsen 144). A new wave of elaborate Warner Bros. backstage

musicals was also just breaking in

1933, which may have further influenced Ibsen’s conception for his own backstage-musical

farce. Op med hodet appropriates two song melodies written directly for the 1933 Warners musical 42nd Street, namely “Young and Healthy” and “Shuffle Off to Buffalo,” while also borrowing character

types and plot situations from the American backstage-musical

genre (Hirschhorn 129).

A Harold Lloyd-inspired slapstick comic protagonist within a backstage musical milieu

are the Hollywood popular-genre inspirations underpinning Ibsen’s narrative. Ibsen’s

career-long dialogue with American cinema developed out of an apprenticeship he served

at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Hollywood from 1923 through

1925. Ibsen worked as a crew member with two legendary silent film directors, Swedish

émigré Victor Sjöström and Texas-born King Vidor, before being transferred to the

studio’s Story Dept., after they realized he was related to Henrik Ibsen. During his

tenure at MGM, none of Ibsen’s screen scenarios were accepted for production, mostly

because of their anti-formulaic, avant-garde ideas (Ibsen 80-121).

While Ibsen self-consciously appropriates Hollywood sources for his own purposes in

Op med hodet, he is first and foremost a European filmmaker working within a European cultural

heritage. Ibsen’s avant-garde experimentation in his 1933 Norwegian film reflects

his awareness of literary and cinematic modernist developments within the larger European

cultural world. His experiments to convey subjectivity and inner states of mind and

emotion in Op med hodet have roots in the literary modernism pioneered by writers such as Knut Hamsun. Ibsen

also draws inspiration from the avant-garde European film movements of the 1920s,

most notably Soviet montage, French Impressionism, Dadaism, and German Expressionism.

Yet Op med hodet emerges as more than a pastiche of its influences, partly through Ibsen’s artistic

assimilation of these disparate elements into his own personal vision and creative

fantasies.

Within the world of the musical-revue theatre later in the film, Ibsen continues to

experiment with multiple means of conveying subjectivity and altered states of consciousness.

As Theobald prepares to go on stage opening night in the role of Hamlet, he peers

at the audience through a viewing hole in the stage curtain. In a subjective point-of-view

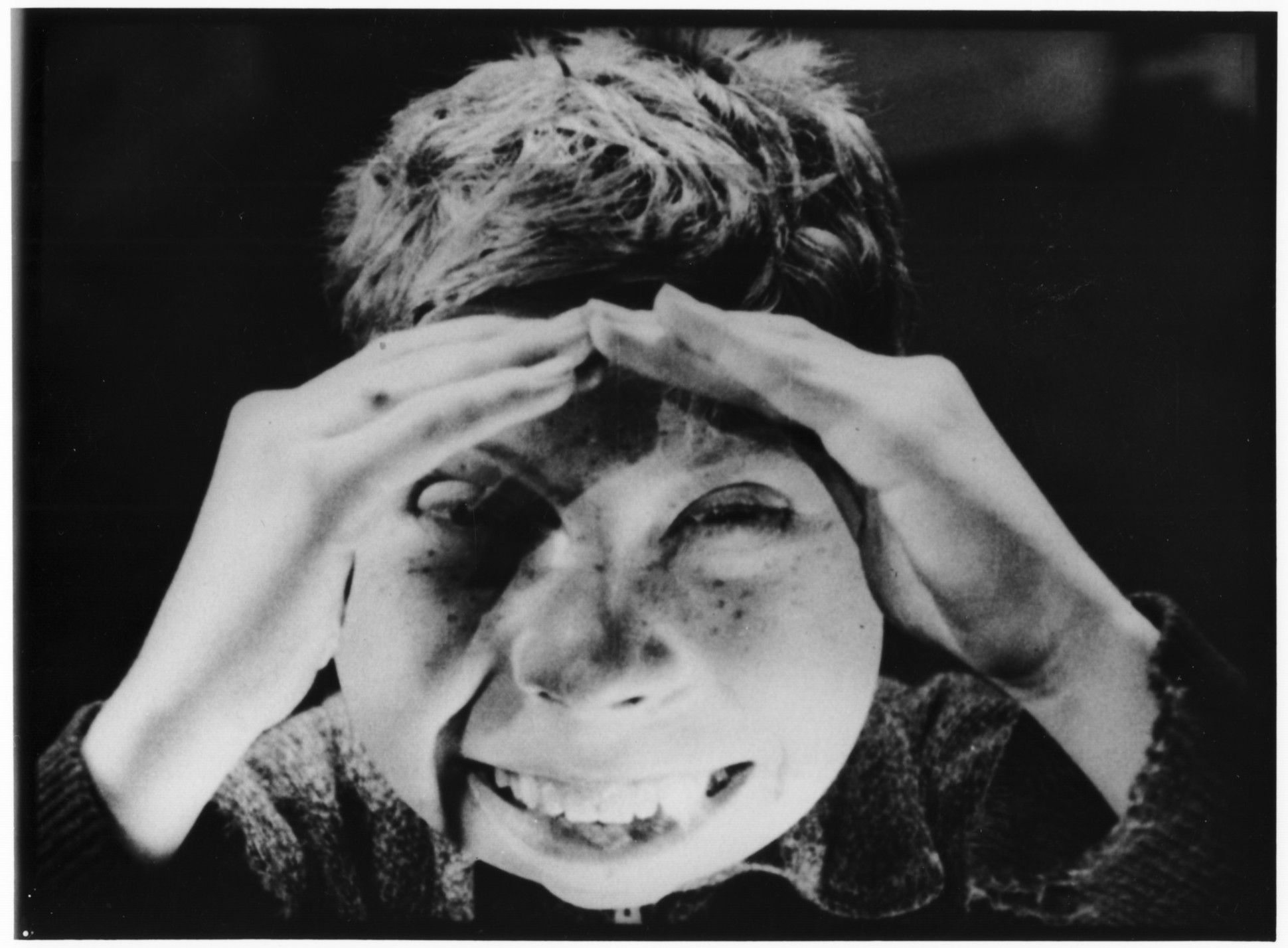

shot, Theobald sees a huge, cruel face eerily looming amid the audience (Figure 8).

The shot effectively expresses Theobald’s fears of ridicule and rejection, as well

as personifying the large audience as a hostile, single entity. Borrowing stylistic

techniques from German Expressionist cinema of the 1920s, Ibsen conveys cinematically

psychological states of angst and near-insanity. In another subjective point-of-view

shot, Theobald sees a backstage manager who is glaring at him slowly dissolve into

a bulldog (Figure 9).

Figure 8

Figure 9

One of Ibsen’s modernist concerns within Op med hodet is the fragile barriers between reality and illusion. Once Theobald enters the illusionist

world of the theatre, nothing is as it first appears to be. In this closed theatrical

universe which obscures the difference between real and illusionary dimensions, between

life and imitation, Theobald cannot read its codes correctly and finally experiences

a nervous breakdown on stage in which he surrenders to the surreality of his condition.

Ibsen is commenting on the fragility of modern self-identity as Theobald slowly descends

into a kind of madness. Yet Ibsen also plays with Theobald’s choice of the role of

Hamlet, another young man who is gripped by indecision and stage fright, and who at

last succumbs to his delusions. That both Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Tancred Ibsen were

burdened with “father” complexes makes the parallel even more intriguing.

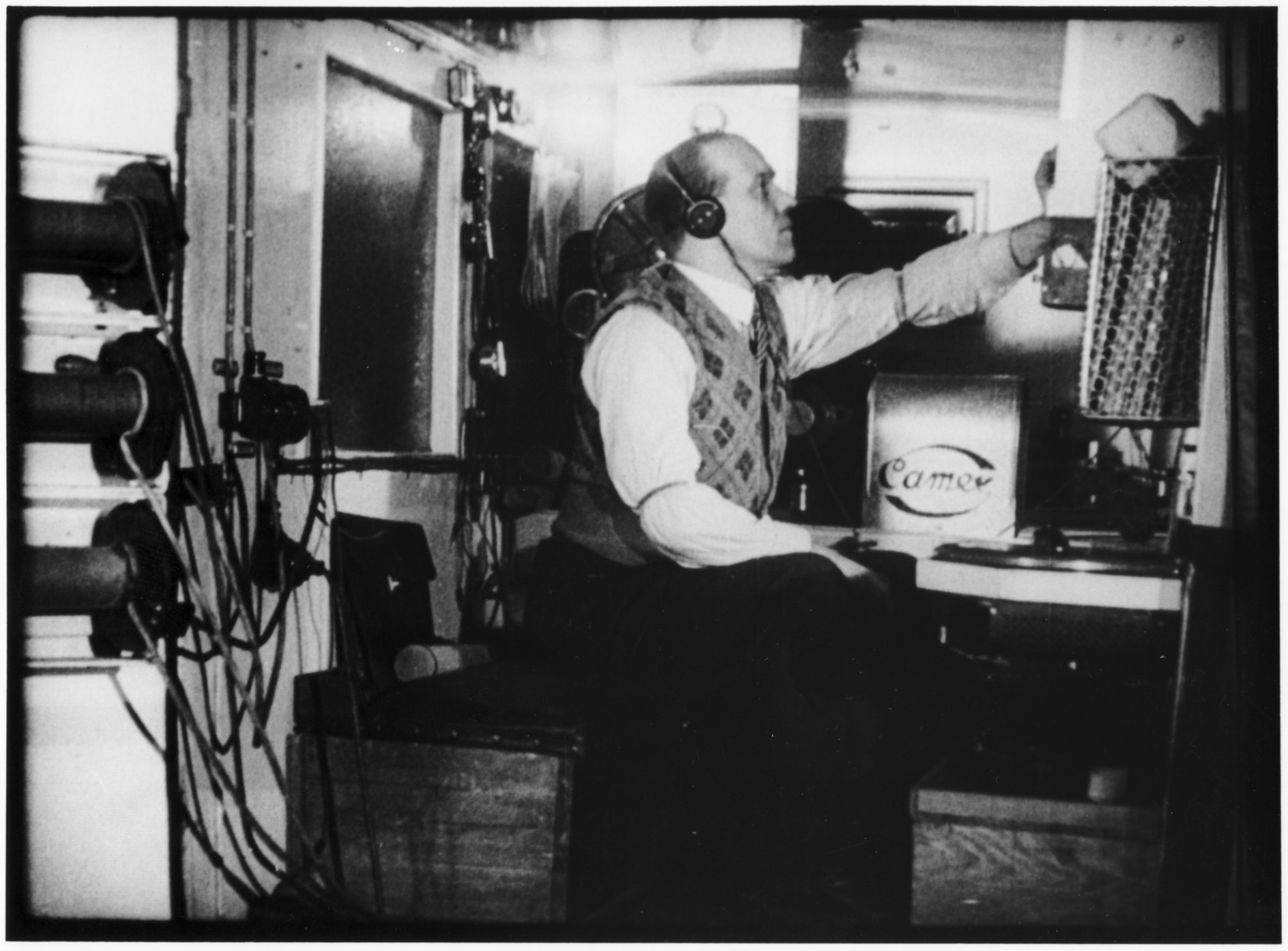

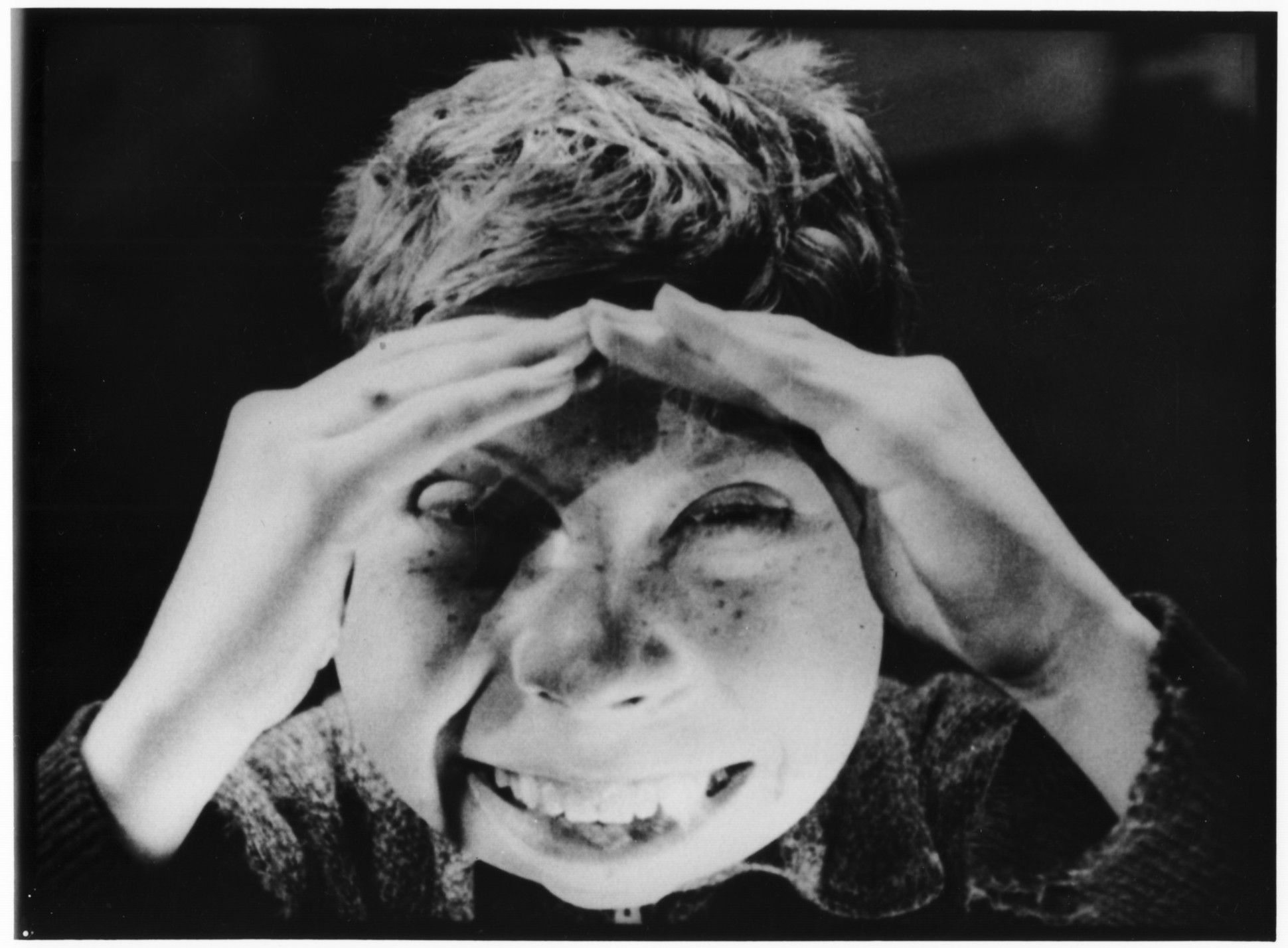

As an avant-garde filmmaker, Ibsen plays illusionist tricks on us, the film spectators,

as well. In one shot, we see a young backstage worker’s face appearing flattened and

widened into a distorted, grotesque shape (Figure 10).

The boy has been holding a large, anamorphic fisheye lens in front of his face,

a fact we realize only after he lowers the lens and his face instantly regains its

normal appearance. The visual gag has a funhouse-mirror cleverness, as well as allowing

Ibsen to comment on the nature of film trickery and effects. Deception and illusion

are part of the film-magician’s art, as this before-and-after look through an anamorphic

lens (a key tool of German Expressionist cinema) reminds us.

The boy has been holding a large, anamorphic fisheye lens in front of his face,

a fact we realize only after he lowers the lens and his face instantly regains its

normal appearance. The visual gag has a funhouse-mirror cleverness, as well as allowing

Ibsen to comment on the nature of film trickery and effects. Deception and illusion

are part of the film-magician’s art, as this before-and-after look through an anamorphic

lens (a key tool of German Expressionist cinema) reminds us.

Figure 10

In another optical-illusion prank on his film audience, Ibsen cuts to a close-up of

the back of someone’s head. This figure’s hair is being gently combed. Then a hammer

suddenly drives a nail into the top of the head’s skull. Quickly the camera pulls

back to reveal that it’s only a wig mounted on a mannequin head. This sleight-of-perspective

shot (and several others) in Op med hodet have links to French Dadaism and the avant-garde films of René Clair, with their

dream-like logic and self-delighted playfulness and irreverence. Through all of Ibsen’s

visual pranks on the film spectator, he foregrounds his feature fiction film as a

construction, subverting the illusions of classical Hollywood narrative by calling

attention to the very act of watching a film (Figure 11).

As a modernist, Ibsen consistently works against the genre conventions of his narrative

through increasingly fragmenting his film’s linear and logical progression.

As modernist poets were interested in replacing logical exposition with collages

of fragmentary images, so does Ibsen achieve modernist collages of image and sound

in Op med hodet. Inspired by the silent-period Soviet-montage editing rhythms of Eisenstein and Vertov

for his visuals, Ibsen attempts pioneering uses of sound and music to counterpoint

his images. The film’s often discordant jazz score works together with montage sequences

to express the frenzied pace and confusion of the rehearsals, construction and mounting

of the musical-revue production within the diegesis, often using musical instruments

to replace human voices.

As modernist poets were interested in replacing logical exposition with collages

of fragmentary images, so does Ibsen achieve modernist collages of image and sound

in Op med hodet. Inspired by the silent-period Soviet-montage editing rhythms of Eisenstein and Vertov

for his visuals, Ibsen attempts pioneering uses of sound and music to counterpoint

his images. The film’s often discordant jazz score works together with montage sequences

to express the frenzied pace and confusion of the rehearsals, construction and mounting

of the musical-revue production within the diegesis, often using musical instruments

to replace human voices.

Figure 11

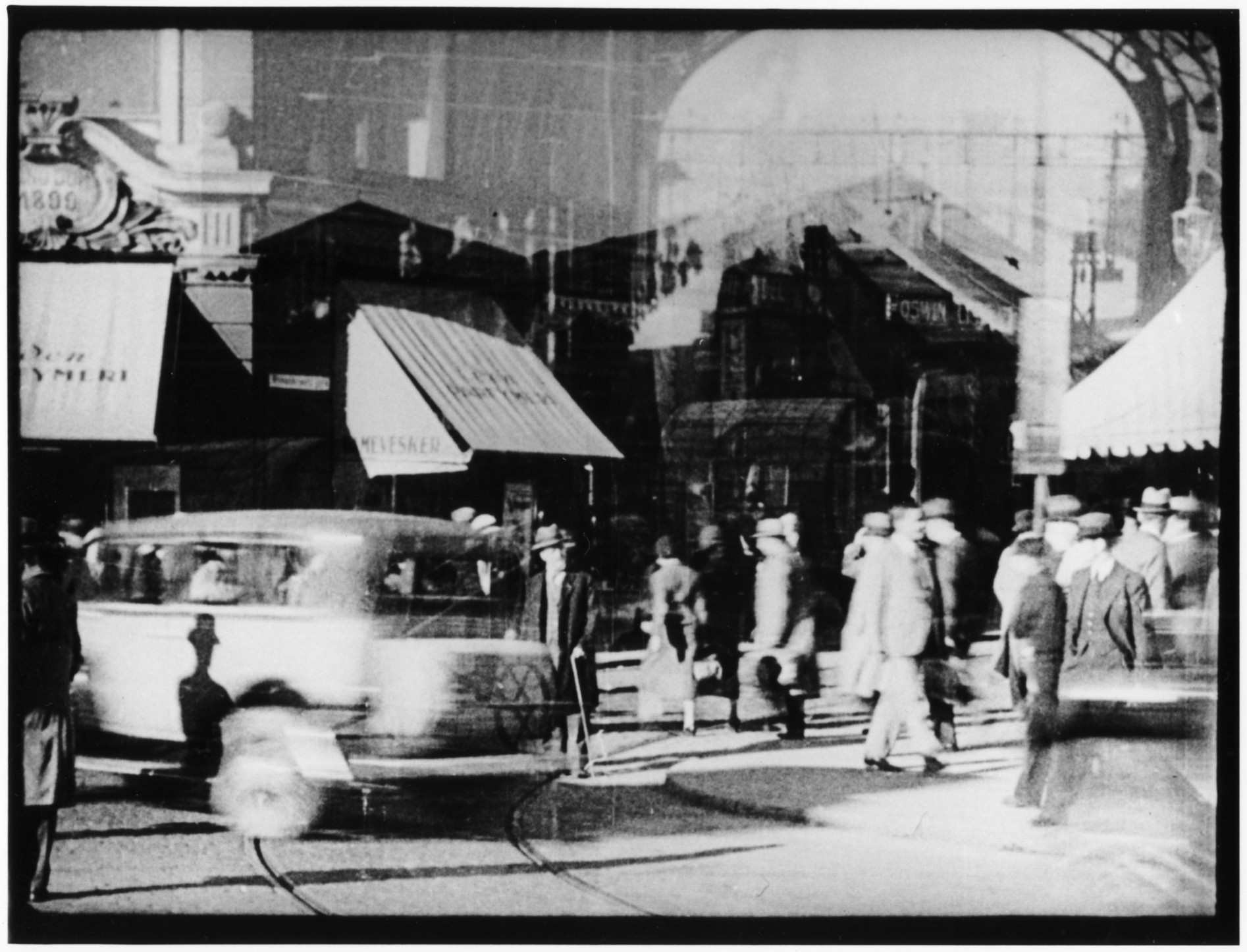

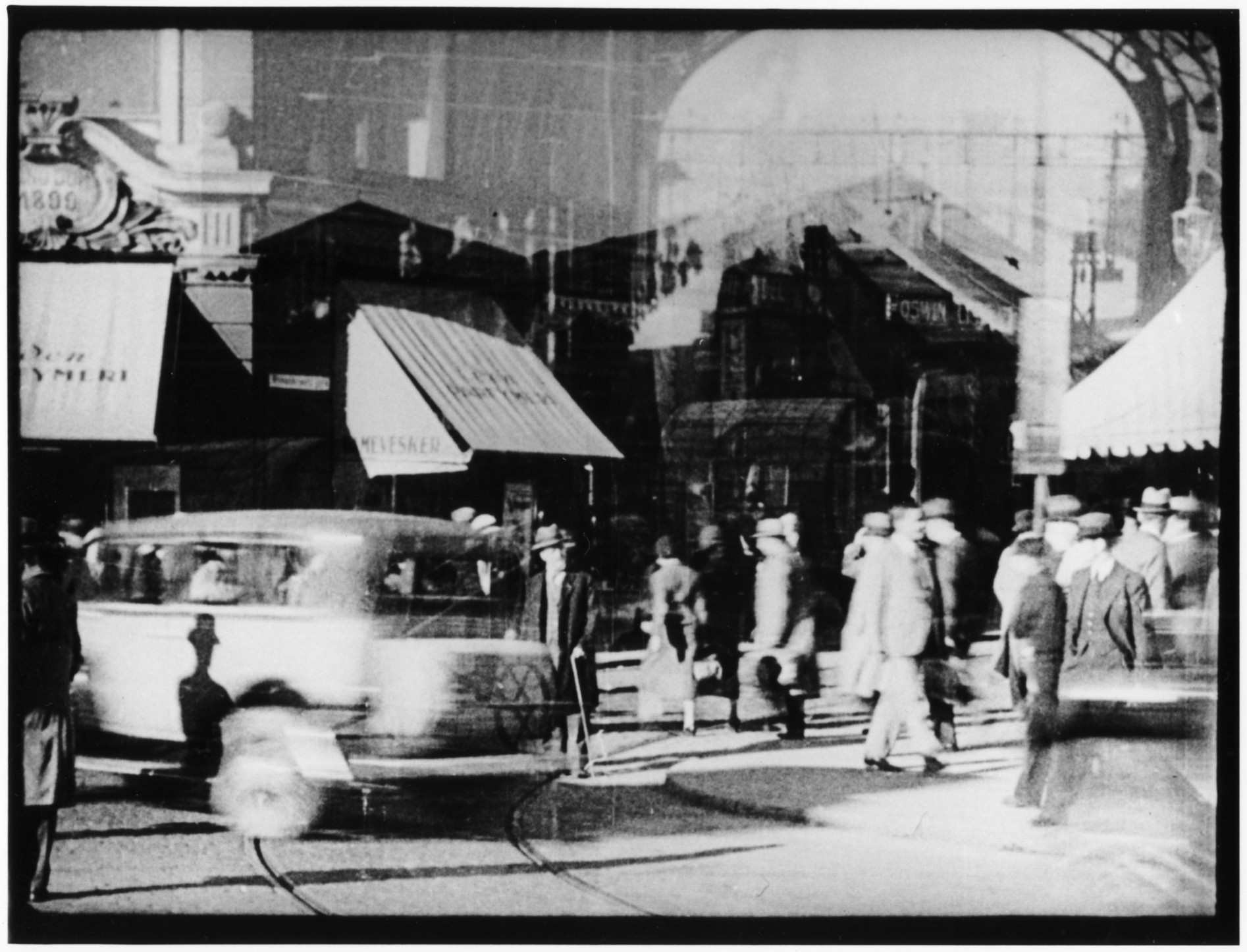

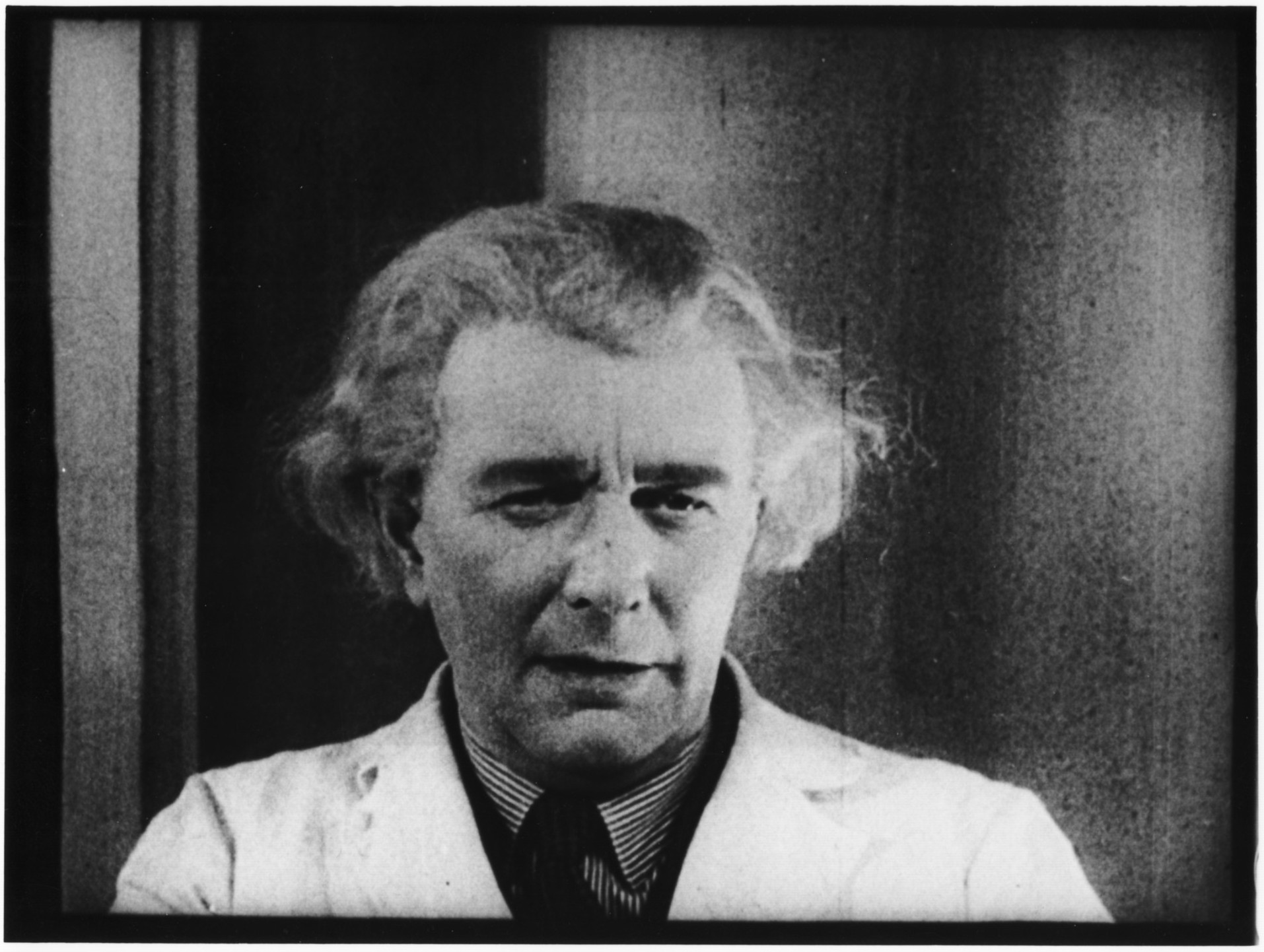

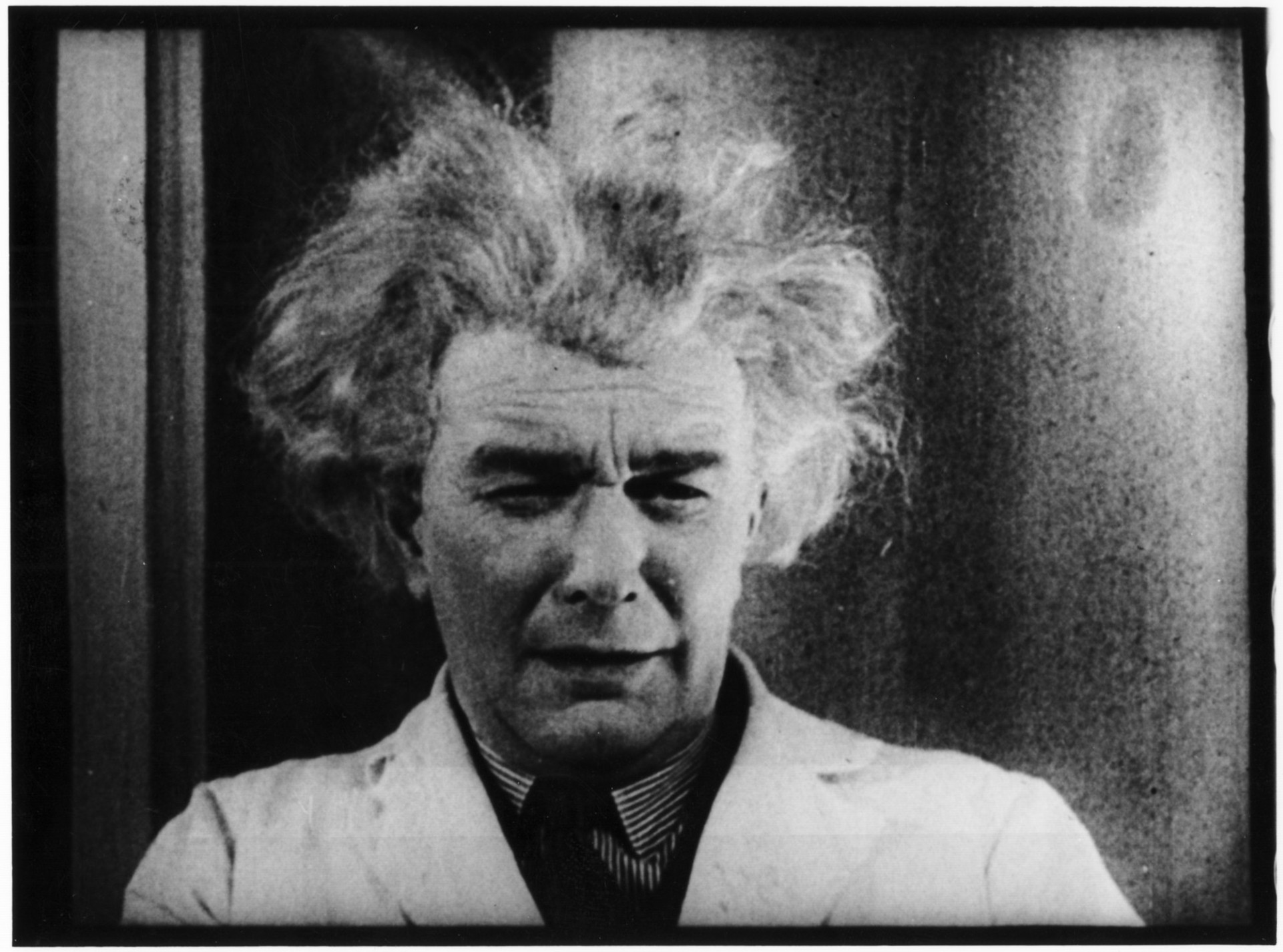

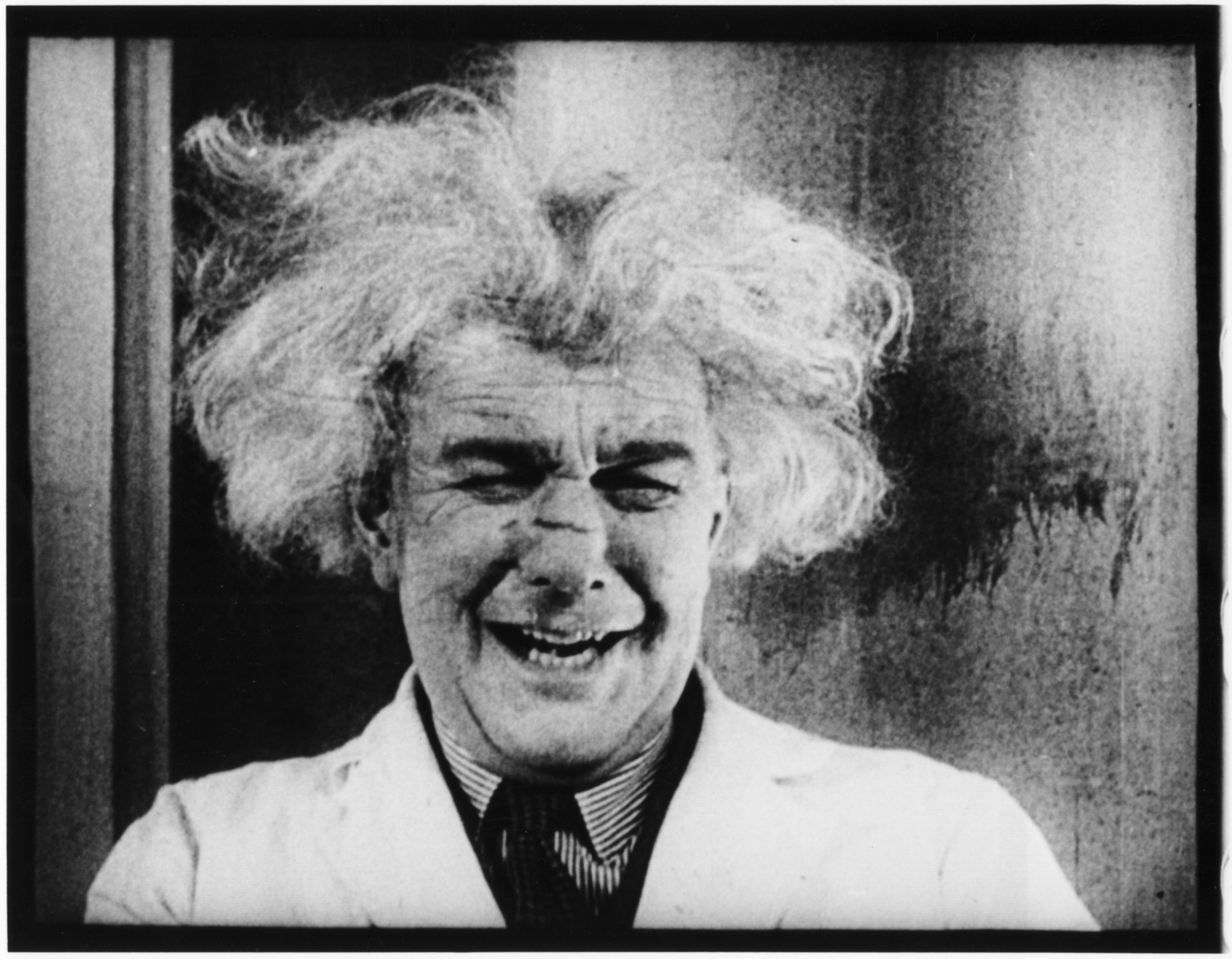

Theobald’s psychological breakdown near the film’s end is expressed in a waking nightmare

of subjective images and sounds, mixing together a montage of surreal images with

a jazz score rising to a cacophonic crescendo. The sequence employs stop-action animation,

reverse-motion, multiple exposures, and optical distortions to suggest Theobald’s

psychological dislocation and near-insanity (Figures 12-15). Here especially Ibsen

attempts a cinematic equivalent to the modernist literary experiments in poetry during

the interwar period. A conventional happy ending unites Theobald and his chorus-girl

love interest Lill in a marriage proposal on stage and a romantic embrace in the film’s

fadeout. Yet Ibsen has so subverted the popular-genre conventions of his film through

increasingly intercutting visual and aural effects expressing dislocation, alienation,

and fragmentation, that Op med hodet’s ultimately conveys dissonance and ambivalence rather than formulaic resolution

and harmony.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

The film’s modernist experimentation undoubtedly contributed to its commercial failure

in early 1934. The film also met no pre-existing genre expectations. Having previously

directed the two highest-grossing films in Norwegian film history up until that date,

Tancred Ibsen attempted with Op med hodet his hitherto most artistically-ambitious project, one his audience rejected. Outside

of occasional revival screenings at the Norwegian Film Institute in Oslo, the film

remains a rarity and has never been released on video or DVD to my knowledge. Yet

despite the film’s initial failure and subsequent neglect since its release, few of

Tancred Ibsen’s films reveal the artist’s ambitious and eclectic modernist vision

so clearly.

In conclusion, Tancred Ibsen deserves more recognition abroad as one of Scandinavian

cinema’s most inventive and versatile auteurs of the 1930s and 1940s. His pathfinding

achievements also showed the way for the next generation of Norwegian writer-directors

such as Arne Skouen, Edith Carlmar, and Erik Løchen. Burdened with being born the

dobbeltbarnebarn of Norway’s two most celebrated nineteenth-century literary figures, Ibsen found

a means of expression unavailable to his grandfathers and tried to make his own mark

as an artist. But since Norway’s undercapitalized national film culture was a marginal

player compared to the Swedish and Danish film industries, Ibsen’s films never were

exported very far outside their own domestic market. In Ibsen’s 1976 autobiography,

Tro det eller ei [Believe It or Not], two years before his death, he complained bitterly that his films rarely if ever

appeared on Norwegian state television and were in danger of being forgotten. Today,

however, Fant and Gjest Baardsen are among the most popular and beloved of Norwegian film classics, and Ibsen’s standing

as the godfather of Norwegian cinema is far more secure. Meanwhile, Op med hodet, his experimental avant-garde backstage musical that failed, deserves fuller recognition

as a key film in Ibsen’s development as a film artist in the early 1930s.

REFERENCES

- Braaten, Lars Thomas, Jan Erik Holst, and Jan H. Kortner, eds. 1995. Filmen i Norge: Norske kinofilmer gjennom 100 år. Oslo: Ad Notum Gyldendal.

- Eisner, Lotte. 1969. The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hirschhorn, Clive. 1979. The Warner Bros. Story. New York: Crown.

- Ibsen, Tancred. 1933. Op med hodet. Kamerafilm.

- ⸻. 1979. Tro det eller ei. Oslo: Gyldendahl Norsk Forlag.

- Iversen, Gunnar. 1993. Tancred Ibsen og den norske gullalderen. Oslo: Det norske filminstitutt.

- Lunde, Arne. 1996.

Tancred Ibsens Op med hodet: avantgarde/backstage-musikalen som slo feil [Tancred Ibsen’s Cheer Up!: The avant-garde backstage musical that failed].

Z Filmtidsskrift 58: 16-29. - Lutro, Dag. 1980.

Tancred Ibsens filmer.

Film og Kino no. 5A: 1-88. - Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell. 1994. Film History: An Introduction. NewYork: McGraw-Hill.