SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 19 (2010) pp.42-54.

Title: Land og synir: An Interview with Ágúst Guðmundsson

Author: Ágúst Guðmundsson

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Statement of responsibility:

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Editor/Rédacteur

John Tucker University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Editor:

John Tucker

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal

Source(s): Guðmundsson, Ágúst. 2010.

Land og synir: An Interview with Ágúst Guðmundsson.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 19: 42-54.

John Tucker

Ágúst Guðmundsson

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- Land og synir [Land and Sons]

- Ágúst Guðmundsson

- Guðmundsson, Ágúst

- cinematic adaptation

- Icelandic cinema

- Indriði G. Þorsteinsson

- Þorsteinsson, Indriði G.

- MDH: started markup 31st August 2010

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 15th November 2010

- MDH: added page numbers from print journal edition 11th April 2012

Land og synir: An Interview with Ágúst Guðmundsson

Ágúst Guðmundsson

ABSTRACT: Land og Synir, based on a novel of the same name by Indriði G. Þorsteinsson, was the first feature-length

film supported by the Icelandic Film Fund after its founding in 1978. Premiered in

1980 to great enthusiasm at home and warm, intelligent approval abroad, the film remains

the benchmark for the Icelandic film industry that it inaugurated. The interview that

follows a brief introduction intends to give Ágúst Guðmundsson, the author of the

film, an opportunity to reflect on its achievement thirty years on, in the light of

his subsequent successful career and the emergence of filmmaking as a major art form

and industry in Iceland. The Editor.

RÉSUMÉ: Land og Synir, inspiré du roman éponyme d’Indriði G. Þorsteinsson, fut le premier long-métrage

islandais parrainé par le Fond Islandais du Film après sa création en 1978. Ce film,

dont la première eut lieu en 1980, suscita beaucoup d’enthousiasme en Islande et reçu

un accueil chaleureux à l’étranger, devenant ainsi une référence pour l’industrie

cinématographique islandaise qu’il inaugurait. L’entrevue, qui sera précédée d’une

brève introduction, aura pour but de donner à l’auteur du film, Ágúst Guðmundsson,

l’opportunité de s’exprimer sur l’ensemble de ses réalisations des trente dernières

années, à la lumière d’une carrière réussie et de l’émergence de la réalisation cinématographique

en tant que forme d’art en Islande. L’Éditeur.

Land og synir [Land and Sons] was the first success the Icelandic Film Fund, which came into existence in 1978,

awarding grants to three films that year. All three went into production in the summer

of 1979. Land og synir was the first to be premiered, in January of 1980. The film was an immediate hit

in Iceland, where it is said that more than a third of the population, roughly 100,000

people, went to see it—52,000 in one Reykjavík cinema alone, during a seven-week period.

As we shall see below, it was also warmly received by critics abroad.

The film is an adaptation of a novel of the same name by Indriði G. Þorsteinsson a

novelist who was also a journalist and newspaper editor (and father of the well-known

crime fiction writer Arnaldur Indriðason). Indriði not only provided the original

story, he also helped finance and promote the film through his contacts in the newspaper

world. Jon Hermannsson produced the film, the first in his career as a film producer.

The budget for the film was $150,000.

Filming, which took place on location in a valley in the north of Iceland—Svarfaðardalur,

near the village Dalvík—, lasted seven weeks, ending with the sheep round-up on the

20th of September. The snowstorm that contributes to the dramatic atmosphere of the

round-up in the film came as a bit of a surprise, but weather is seldom an unimportant

factor in a film shot in Iceland. The interiors were also shot locally, and even the

costumes were obtained in the area.

Most of the actors, including the female lead Guðný Ragnarsdóttir, who plays Margrét,

were amateurs. Two, however, were well-known professional actors: Sigurður Sigurjónsson,

who plays the male lead, and Jón Sigurbjörnsson, who plays his neigbour, Margrét’s

father. Sigurður Sigurjónsson went on to become one of the most popular comedians

in Iceland. Jón Sigurbjörnsson has had a distinguished career too, appearing also

in Ágúst Guðmundsson’s Útlaginn [The Outlaw] and Gullsandur [Golden Sands], among other films. Crew members similarly later worked with the director: for example,

Sigurður Sverrir Pálsson, the cameraman, who also shot the two films just mentioned

and many others. The film’s composer was Gunnar Reynir Sveinsson, a Netherlands trained

musician, with a background in jazz.

Land og synir went to many film festivals, including the Taormina Festival in Italy, where it won

the silver award. It was Iceland’s entry for the best foreign film of 1981. The following

passages give a sense of the response of foreign film reviewers.

Variety, October 29 1980, by “Robe”

… This first feature shows the result of sticking to the first law of filmmaking—surround

yourself with skilled technicians. Sigurdur Sverrir Palsson’s color camerawork makes

what is generally considered a cold land look warm and inviting. Indeed, one wonders

if any other farms (possibly in New Zealand) have such a combination of rich land

and spectacular scenery.

Most of the film’s acting falls on the sturdy shoulders of young Sigurdur Sigurjonsson,

but he’s given plenty of support by a stunningly beautiful young actress, Gudny Ragnarsdottir

(a teenage Candice Bergen). Most of the character people are also topnotch. A very

worthy beginning.

New York Post, November 21 1980, by Archer Winsten

Iceland’s Classic

… Land and Sons, by Agust Gudmundsson, another small masterpiece from Iceland.

This last picture is something I would like to emphasize. Watching it I was struck

by the horrible contrast with American films that too often trashily cater to the

markets of pornographic sex, bloody violence, sci-fi fantasy and nightmare horror

that gives kids the creeps.

Quite simply, and with beautiful realism, Land and Sons deals with a remote farm in Iceland where the father refuses to face his mounting

debt and accept his son’s preference to move to the city, Reykjavik. The father dies

after an operation in the hospital, the son kills and buries his favorite horse, sells

off the sheep and other horses, sells the land, gets himself out of debt and goes

to the city.

The neighboring farmer’s well to-do daughter has tried to persuade him to stay on

the farm, and her father has remarked that everyone in Iceland is in debt and no one

will ever pay.

It is a quietly told epic of land and city, of plain people whose concerns avoid all

taint of theatricality. It is a noble film, doubtless much too good to be grabbed

by commercial exhibitors who have so successfully corrupted all of us.

Hollywood Dramalogue, April 9 1981, by Donna M. Matson

The first feature film to be produced in Iceland, Land and Sons is a probing, austere portrait of a young man’s yearning for big-city life that uproots

him from his ancestral farm after his father’s death. Set in 1937, it explores the

factors that led to large-scale migration of Iceland’s rural populace to its larger

cities. Director Agust Gudmundsson tells the story visually with little dependence

on dialogue, making Land and Sons a stern yet lyrical study of man’s relationship with the earth. Sigurdur Sigurjonsson

and Gudny Ragnarsdottir give fresh, sincere performances as the young man and his

first love.

The Reader, April 10 1981, by Dan Sallitt

Land and Sons. An intelligent, quietly graceful debut by direrctor-screenwriter Agust Gudmundsson,

which deserves better than to be known as the most successful Icelandic film. The

story deals with a subject also treated in Bergman’s Faro Document 1979: the younger

generation’s unwillingness to continue working the often-unprofitable farms that were

a way of life to the parents. A restless son (Sigurdur Sigurjonsson), prepared to

leave Iceland for the Danish mainland [actually another part of Iceland], is given pause by his awareness of tradition and his awakening love for his neighbor’s

daughter (Gundy [sic] Ragnardsdottir). The film’s great virtue is the calm and gravity

with which it treats this dilemma; Gudmundsson’s thoughtful, literate script provides

each of the characters with his or her own respectable justifications, and the awesome

Icelandic landscape and the parable-like narrative unobtrusively create a mood of

universality. Land and Sons is not the type of film to cause a stir at a film festival, but it manages to be

effectively entertaining as it slowly unfolds its understated despair.

Hollywood Reporter, April 10 1981, by Ray Loynd

Iceland, a country still undiscovered by most of the world, turned out a movie last

year called “Land and Sons,” and the event reportedly was a major celebration. Filmex

reports the film is Iceland’s most popular 35 mm feature and almost half that country’s

population saw it. Indeed, whatever the sparse history of Iceland’s movie industry,

“Land and Sons” certainly qualifies as a distinguished achievement for a young filmmaking

industry.

Made with the support of the government’s newly founded Film Fund, and a feature debut

for director-producer-screenwriter Agust Gudmundsson, “Land and Sons” dramatizes a

young man’s decision to leave the land he works for the muse of the city. The film

moves with a quiet assurance and a texured stillness that illuminates the sense of

the land and its scattered rural people. Against the rich green hillsides and the

towering mountainscapes, events unfold with universal touchstones: the young man’s

reconciliation to his father’s death, his casually romantic alliance with a local

girl, his decision to sell out against a neighbor’s wishes and change his life.

These solitary moments wed together a land and a people with deceptively easy simplicity.

Daily Bruin, U.C.L.A, April 10 1981, by Michael Auerbach

Agust Gudmundsson’s first feature is a stunning visual travelogue, an acute social

treatise and an engaging piece of history. The action takes place during the Depression,

when many members of the Icelandic farming communities migrated to Reykjavik in search

of better opportunities. This is a sort of Icelandic Three Sisters, in which the main character resists the pressure to leave his home until the death

of his father (which, not coincidentally, corresponds with the first sign of the death

of traditional values). Land and Sons is a quiet, restrained prelude to an epic: sheep-farming and raking the grass take

precedence to petty human intrigues.

LA WEEKLY, April 10 1981, by “MV”

There is so much noisy drivel on film that it’s hard to make enough of a stir when

something quietly epic like Land and Sons appears—a rare work that is not only “a good film” (meaning something emotional to

watch) but that rejoins us with a historical memory

we very much need. For we’ve virtually forgotten that most of us have forebears who

left off working the land sometime in the last 200 years—that they were wrenched from

the land by forces they barely understood, instinctively hated, and were powerless

to oppose. We’ve been educated to be good corporation, factory and service workers,

so our education neglected to remind us to remember, much less to grieve, what once

happened to our families. The Icelandic film Land and Sons gives us back their memory. Important and beautiful, the film is a social and cinematic

companion to Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs. Olmi gives us the last days of the peasant, and Agust Gudmundsson’s Land and Sons gives us the last days of the yeoman farmer. But this isn’t merely a document—or,

better put: the value of Land and Sons as a document is precisely its emotional value, how gripped we become by these people,

their dreams and needs. It gives us back the understanding grief which is the least

our forebears deserve from us. And with a profound visual alchemy it gives them back

to the land: the camera makes the land look like what it is, not a backdrop but something

quietly alive, a great life upon which the small lives of us take shape. It’s as though

the people in the movie are being watched from the point of view of the land—and there

is such a completeness to this feeling, it is even as though the grief at their loss

is the land’s own grief.

The Interview, by e-mail, 1 October/8 October 2009:

Q :

How did you decide to become a film maker and how did you go about preparing yourself

for the role of director?

A :

At grammar school, when I was 18, we started up a film club, which became a hit with

all the secondary schools in Reykjavik and the University of Iceland. I spent a whole

year watching all the most important classics, from Intolerance onwards. I remember we included a complete program of Dreyer and quite a few Kurosawa

movies. After studying Icelandic at the university and drama at the National Theatre

Drama School, going to a film school in England was a natural continuation of my studies,

despite the fact that there was no film industry to speak of in Iceland at the time.

By then I had also had a leading role in a TV play, which rather whetted my appetite.

Q :

Which filmmakers most influenced your decision to become a filmmaker yourself? Which

have most influenced your practices and style as a filmmaker as your artistic life

has evolved?

A :

Two European “waves” were very important for me: the French New Wave and the Czechoslovakian

one. The

film club was really run by myself and another lad, and we were regularly invited

to the Czechoslovakian Embassy to see the latest films from their home country. This

was in the sixties. It was awesome to feel the pride with which they showed these

films, to experience how important feature films can be to a small nation. This is

where I saw for example Black Peter by Milos Forman, which came even before A Blonde in Love and The Firemen’s Ball. — My idol from the French New Wave was always Francois Truffaut. His lightness of

touch has a lot in common with that of the Czechs.

Q :

What combination of factors made it possible for you to film Land og synir in 1980. Was more money available in Iceland? Had technological developments made

film making less expensive or simpler? Had fashions in film come to welcome a relatively

low budget, independent film?

A :

The film fund was established in 1978, and I and my partners got one of first three

production grants. Filming was expensive, but we saved on everything. The film stock

was short-ends, i.e. returned stock from other productions; we used an old Arriflex

camera which was put in a blimp, a rather cumbersome box, to enable sound recording.

—When I look at the film now, I think the limitations under which we worked were,

in the end, beneficial. It gave the final result a certain style in line with the

subject matter. We had, for example, only three lenses. Almost all the film is shot

with two of them: the 50mm and the 28mm.

Q :

For your first film you chose to adapt a well-known literary work. What led you to

this decision and what did you gain and lose by making it?

A :

I met the author of the novel when we took part in a TV talk show about the future

of the film industry. I remember that we were the most optimistic of the panel, totally

convinced that we could make feature film in Iceland. Afterwards I told him I thought

his novel Land og synir was fine film material and he suggested a further chat over a cup of coffee. That

was the beginning of our company, Ísfilm. Anyway, starting with a novel was probably

a sensible thing to do.

Q :

Land og synir tells a common story but gives it an Icelandic inflection. Was it a story that you

knew from your own experience? Did its poignancy recommend it to you?

A :

I had certain affinities with the subject matter. It’s about the move from the rural

areas, which resulted in the building up of Reykjavík. My parents came from the Westman

Islands; they moved to Reykjavík to take part in creating an urban society for the

first time in Iceland. I thought it was an important story to tell, and I liked the

way it was told. Indriði, the writer, was a tough fellow on the surface, but his novels

were written with wonderful sensitivity.

Q :

What process do you use to develop a screenplay? As taught (and practiced, I believe)

screenplay writing seems a remarkably hide-bound process, do you try to follow its

rules (using a non-proportional font for example) when you will be the director working

from the screenplay?

A :

Turning a novel into a screenplay usually leads to a certain clash of interests: keeping

the free spirit of the novel doesn’t always go hand in hand with following the rules

of the screenwriting trade. When I’ve adapted something from a written source I have

always had a tendency to treat the original with a lot of respect. In at least one

case, with too much respect. A film is actually a lot stricter in its narrative shape

than a work of literature. There are certain dramatic elements you need to take into

consideration, which the novelist doesn’t necessarily have to bother about. But in

the case of Land og synir, this was never an issue. The novel has a certain cinematographic feel to it. It

almost reads like a screenplay.

Q :

To what extent do you use storyboards? To what extent is filming for you a matter

of making real a complete vision that you have when you start filming? To what extent

do you discover what you are looking for only after you’ve found it?

A :

I’ve learnt to appreciate storyboards. For years I’ve had them made for all action

scenes. However, this depends, of course, on the style of the narrative. I’ve been

involved in films that are virtually improvized in front of the camera. But even in

those cases I usually know what I want to have at the end of the shoot. Which doesn’t

change the fact that the editing is always a process of great revelations. —All the

projects I’m working on now call for careful preparation, and storyboards are a precious

tool in that respect. It certainly helps set your vision before filming starts and

it helps relay your wishes and intentions to the crew.

Q :

Land og synir sets itself the task of documenting Iceland and Icelandic culture on film to some

extent for the first time. Which potential audience most affected your decisions as

to how to present this landscape and culture? a native one presumably eager to see

its stories told on screen or an international one to whom you could serve as a cultural

ambassador?

A :

Land and Sons was made solely for a Icelandic audience. I never even gave it a thought that it

might later be transmitted on television overseas or shown at film festivals. All

that came as a bonus, both for us and for the cultural authorities of Iceland. In

hindsight I can say that my first two films show a certain tendency to make proper

use of the Icelandic landscape, as if we were trying to create our own visual language.

But even that was more for the locals than the rest of the world, at least in those

days.

Q :

If I have understood correctly, your actors include both professionals and people

who had never acted before, including some that you discovered by chance. How difficult

is it to elicit a unified ensemble performances from such a diverse cast? What did

you gain by using unknown actors?

A :

The actors who appeared in the first Icelandic TV plays seemed to come with too much

baggage from the theatre. Therefore I tried to find my cast elsewhere. Finding talent

in someone who had never done any acting at all became a great thrill for me. Still,

the unified ensemble performances you mention were usually brought about with some

help from the professionals. In Land and Sons I had two professionals in the leading male roles. The rest of the cast looked to

them for guidance, especially to Jón Sigurbjörnsson, who played the neighbour. The

farmers felt at home with him. Not surprisingly, a few years later he bought a farm

and has been living there ever since, breeding horses.

Q :

How did you go about assembling the crew you needed to make the film? In later times

you have relied on European funding which has required the use of actors or crew from

different countries, a process which can produce, as you have noted, a Euro-pudding.

Presumably such constraints did not affect this first film, but film production facilities

must have been rather undeveloped in Iceland at the time.

A :

None of us had ever been involved in shooting a feature. We were doing everything

for the first time. I remember thinking to myself: this is the most absurd situation

I’ve ever got myself into. A director has to be ready with all the answers at all

times, and somehow I managed to bluff myself through the production, often pretending

I knew what to do when I didn’t. You may remember the final section of Tarkovsky’s

Andrey Rublyov, about the boy who convinced everyone he knew how to cast a bell, while he was really

only going on a hunch. That’s how I felt.

Q :

What particular difficulties did you experience making the film. Was Icelandic weather

your enemy or your friend?

A :

The weather in the film is considerably worse than in the book. The rounding up of

the sheep took place in fine weather in the book, whereas we had to shoot the actual

incident in a snowstorm. It proved to be just right for the film, though—much more

effective than the sunshine of the novel. There are more exteriors than interiors,

and in general we simply had to take what we got.

Q :

I believe you did your own editing. How did you develop your skills as an editor?

How important do you think your editing was to the success of the film? What principles

do you follow as an editor?

A :

I learnt editing at the film school in England. Luckily I was introduced to some old

equipment, much loved by my editing tutor: the upright Moviola. When it came to editing

Land og synir, we discovered an old machine in Iceland, and that’s what I used to cut the film.

The editing process was a simple one, there was very little to choose from, the ratio

was 6 to 1, which is unheard of in the film business. Putting the film together took

only six weeks.

Q :

How did you go about selecting music for the film? In retrospect how do you judge

the climactic scenes of communal singing during the autumn sheep roundup?

A :

There’s always a lot of singing at these events, it’s a well known tradition. The

guy standing by the lake, singing, is a local teacher, who happens to have this beautiful

voice. For incidental music we mainly used works already recorded, but by the same

composer.

Q :

What reception did Land og synir receive? How successful was it financially and where? Did you find the film reviews

intelligent? Did they in any way contribute to your growth as an artist?

A :

The general public was very appreciative of our effort. The attendance figures for

the first Icelandic films were really astounding. More than a third of the population

saw Land og synir in cinemas, and still it has to be said that the film doesn’t really have the shape

of a blockbuster. The money we earned we used for our second film, our saga film Útlaginn [The Outlaw], which was also well received, but too expensive to ever recoup its cost. —The reviews

for Land og synir were positive, even in the foreign press. I have to admit they served as a tremendous

boost for me personally. A film director needs self-confidence—which is usually in

deplorably short supply.

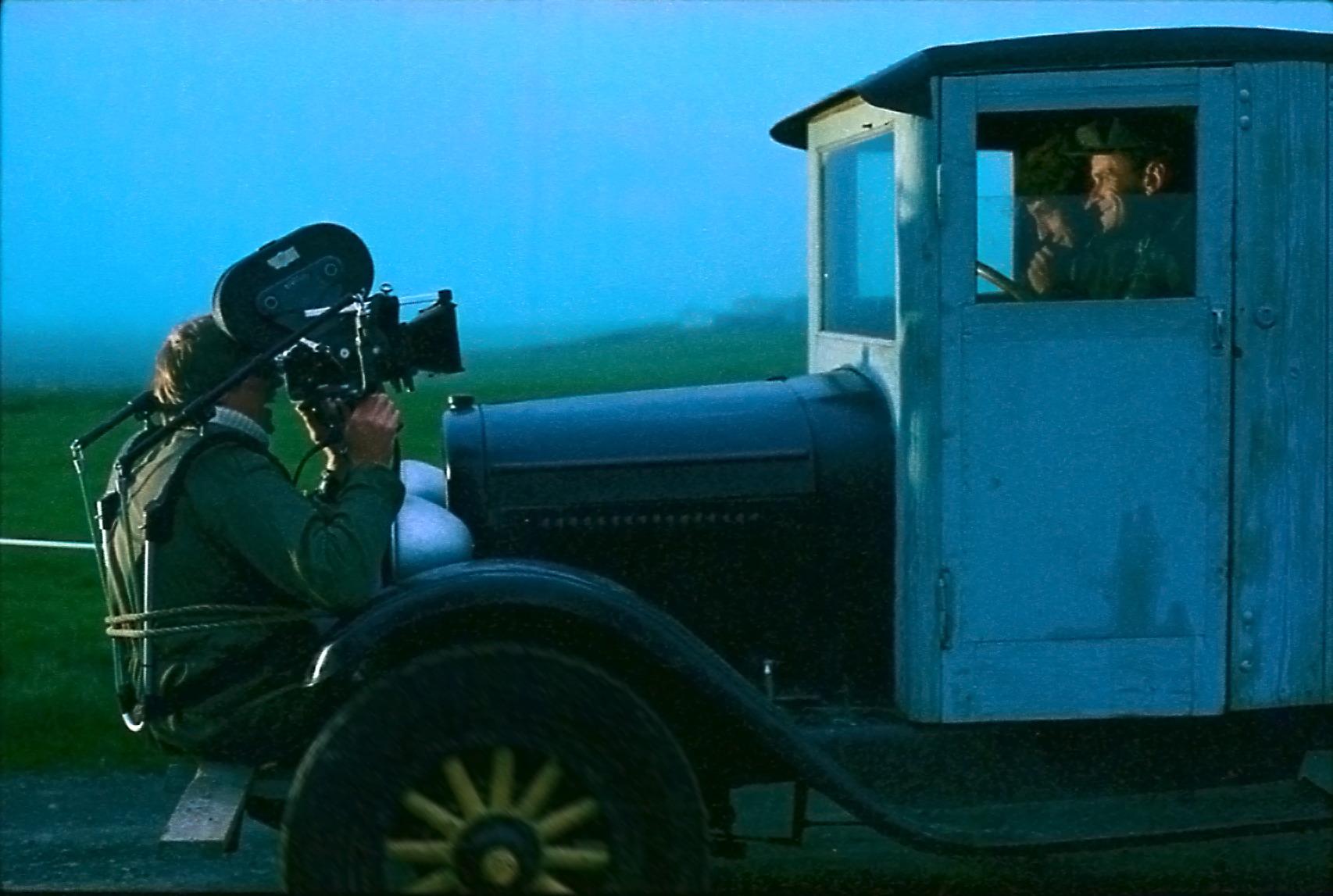

Home-made rigging for the camera. Sigurður Sverrir Pálsson, cameraman, Sigurður Sigurjónsson,

Haukur Þorsteinsson.

Another home-made camera rig. Sigurður Sverrir Pálsson, cameraman, Friðrik Stefánsson,

sound recordist.

I’m talking to Sigurður Sverrir Pálsson, cameraman. In the absence of proper equipment,

we made us of cardboard to flag off light.

When I needed some action for this scene, I remembered the times when I was asked

to singe sheep legs. Guðný Ragnarsdóttir and Sigurður Sigurjónsson

Sigurður Sigurjónsson (furthest to the left) with the local men who played

various roles

The most used still from Land og synir. Svarfaðardalur (by Dalvík)

Indriði, the author of the original novel, played the local minister.

The director and the cameras, the “blimp” on the right.