SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 31 (2024) pp.1-14

DOI: 10.29173/scancan251

Copyright © The Author(s), first right of publishing Scan-Can, licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Assessing the Landscape and Proposing a Way Forward: The Teaching of Scandinavian Politics in Canadian Universities

Authors:

Tyrgve Ugland

Tyrgve Ugland

Statement of responsibility:

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal:

Natalie Van Deusen, University of Alberta

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal:

Natalie Van Deusen, University of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus:

Katelin Parsons, University of Iceland

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus:

Katelin Parsons, University of Iceland

Statement of responsibility:

Production Editor/Directrice de la production:

Robert Crandell, University of Alberta

Production Editor/Directrice de la production:

Robert Crandell, University of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Translator/Traductrice:

Malou Brouwer, University of Alberta

Translator/Traductrice:

Malou Brouwer, University of Alberta

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal.

Source(s): Ugland, Trygve. 2024. “Assessing the Landscape and Proposing a Way Forward: The Teaching of Scandinavian Politics in Canadian Universities.” Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 31: 1-14.

Keywords:

- Scandinavian politics

- Teaching

- Canada

- comparative and inter-disciplinary approach

- RC: started markup September 10, 2024

Assessing the Landscape and Proposing a Way Forward: The Teaching of Scandinavian Politics in Canadian Universities

Trygve Ugland

ABSTRACT: This paper offers a first status report and an analysis of the teaching of Scandinavian politics in Canadian universities. Based on a questionnaire sent out to the 57 affiliated member departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA) in 2022, the paper identifies a clear mismatch between the attention paid to various aspects of the Scandinavian political model among academics and society more generally in Canada, and the very limited number of courses specifically dedicated to Scandinavian politics at Canadian universities during the 2018-2022 period. The paper makes some recommendations on how to promote and integrate Scandinavian politics content more actively into university teaching. Moreover, the paper presents a dedicated course on Scandinavian politics at a Canadian university as an example. The importance of a comparative and interdisciplinary approach to Scandinavian politics is here highlighted.

RÉSUMÉ: Cet article présente un premier état des lieux et une analyse de l’enseignement de la politique scandinave dans les universités canadiennes. Basé sur un questionnaire envoyé aux 57 départements membres de l’Association canadienne de science politique (ACSP) en 2022, l'article identifie un décalage évident entre l'attention portée aux divers aspects du modèle politique scandinave parmi les universitaires et la société plus généralement au Canada, et le nombre très limité de cours dédiés à la politique scandinave dans les universités canadiennes au cours de la période 2018-2022. L’article offre quelques recommandations pour la promotion et l’intégration plus active du contenu de la politique scandinave dans l'enseignement universitaire. En outre, l’article présente un cours dédié à la politique scandinave dans une université canadienne à titre d'exemple. L'importance d'une approche comparative et interdisciplinaire de la politique scandinave est ici soulignée.

Introduction

Surveys assessing the state of Scandinavian studies in North American universities have a longstanding tradition. The analyses have focused on the teaching of Scandinavian languages, literature, culture, history, politics and societies in the United States (see for instance Askey, Gage and Rovinsky; Barton; Bronner and Franzen; Ekman; Gage; Kvavik; Meixner; and O’Neil). Perhaps indicative of a more general trend of declining enrollments, courses and faculty in Scandinavian studies, surveys post-1980s are difficult to come across. Nevertheless, the present paper offers a first status report and an analysis of the teaching of Scandinavian politics in Canadian universities. Based on a questionnaire sent out to the 57 affiliated member departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA) in 2022, the paper identifies a clear mismatch between the attention paid to various aspects of the Scandinavian political model among academics and society more generally in Canada, and the very limited number of courses dedicated to Scandinavian politics at Canadian universities during the 2018-2022 period.

Scandinavian Politics and North America

The idea of a Scandinavian political model started to gain prominence internationally in the aftermath of the Great Depression, and North American scholars and writers were at the forefront of the movement. The American journalist, Marquis Childs’ (1936) international bestseller, Sweden: The Middle Way, represents the earliest reference to Scandinavia as an international political model. However, in the 1940s and 1950s, University of Alabama professor Hudson Strode followed up with several books on Scandinavia, and in Sweden: Model for the World from 1949, Strode, like Childs, praised the Scandinavian political system as an ideal to strive for and argued that leaders and ordinary citizens of any nation would “profit by examining the agreeable Scandinavian compromise between capitalism and socialism” (Strode xx).

Following the early contributions of Childs and Strode, political scientists from the United States have published seminal work on different aspects of the Scandinavian political model. Thomas J. Anton’s (1969 and 1980) studies of Swedish political culture in the 1960s and 1970s became influential and enduring reference points in the policy-making literature. In the field of comparative public policy, Hugh Heclo’s comparison of the British and Swedish old-age pensions and unemployment insurance programmes constituted a major contribution to the discipline. Former president of the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Studies (SASS) Donald Hancock’s work on social corporatism convincingly portrayed Sweden as a leading empirical example of successful system transformation to the post-industrial era. In the award-winning Small States in World Markets, Peter J. Katzenstein demonstrated how democratic corporatism in Scandinavia offered an effective model for larger countries enmeshed in the world economy. Facing demographic, social and economic challenges, Eric S. Einhorn and John Logue (2003 and 2010) provided evidence of how the universal and comprehensive Scandinavian welfare states eased the adjustment to economic globalization. In the areas of foreign policy and international relations, Christine Ingebritsen depicted the Scandinavian countries as “moral entrepreneurs” demonstrating how they exercised considerable influence abroad through their moral leadership. This list is by no means exhaustive, but it clearly demonstrates the significant contributions political scientists from the United States have made to the study of Scandinavian politics and to their discipline.

The Scandinavian political model has also received substantial attention among Canadian political scientists at different time periods and directed at both English- and French-speaking audiences (see for instance Milner 1989 and 1994; Paquin and Lévesque; and Paquin, Lévesque and Brady). Furthermore, in Policy Learning from Canada: Reforming Scandinavian Immigration and Integration Policies, Ugland (2018) demonstrates that the Scandinavian approach to policy learning from abroad resembles the Scandinavian policy making style identified by Anton half a century earlier.

Canadian political debates continue to be saturated with references to Scandinavia as academics, journalists, politicians and leaders of non-governmental organizations continue to evoke Scandinavian solutions to Canadian as well as to global challenges. Deliberations on electoral systems (proportional representation), government formation (coalition and minority governments), policy style and democratic innovation (consensus, openness and transparency); political and economic representation (gender equality), political participation (voter turnout and tripartite arrangements), political priorities (education, environment and energy policies), welfare provisions and health-care delivery (private vs. public solutions; free access vs. user fees; pension reform) and international activism and engagement (humanitarianism and conflict resolution) are only a few examples (See for instance Horváth and Daly; Marier; and Raynault, Côté, and Chartrand). Moreover, the heated battle over the proposed university tuition hikes in Quebec in 2012 and the debate on reform of Canadian prostitution laws around 2013 contained numerous references to the Scandinavian systems for higher education and criminal justice, respectively. The common thread in these debates was that Canada could learn worthwhile lessons from Scandinavia.

The wider international fascination for everything Scandinavian, ranging from literature, music, films, TV series, food, design, fashion, lifestyle, as well as politics has been particularly visible during the past decade (see for instance, Boot; Partanen; and Wiking). In 2013, the Economist magazine featured a bearded, overweight, horned helmet-wearing Viking on its front cover, accompanied by the headline, “The Next Supermodel”. The overriding message was that “politicians from both left and right can learn” from the Scandinavian countries (9).

The purpose of this paper is to investigate to what extent the substantial interest in Scandinavia and Scandinavian politics in Canada and internationally was reflected in the course offerings at Canadian universities during the 2018-2022 period. In addition to identifying where and how Scandinavian politics courses were taught in Canada, the paper will also make an argument for an intensified focus on Scandinavian politics through both dedicated courses on Scandinavian politics, but also through the integration of Scandinavian politics content in other courses in comparative politics or other sub-fields of political science or outside the discipline. The paper makes some recommendations on how this can be achieved in practice.

Scandinavian Politics in Canadian Universities

Scandinavian Studies is an interdisciplinary academic field of area studies, where courses may focus on a wide variety of topics like Scandinavian languages, literature, culture, history, politics and societies. Although a course on Scandinavian culture or history often will cover political content, this paper focuses explicitly on the teaching of Scandinavian politics with the discipline of political science.

Within the discipline of political science, Scandinavian politics courses would typically be offered in one of the following subdisciplines depending on the focus: comparative politics, public policy and administration, political economy or international relations.

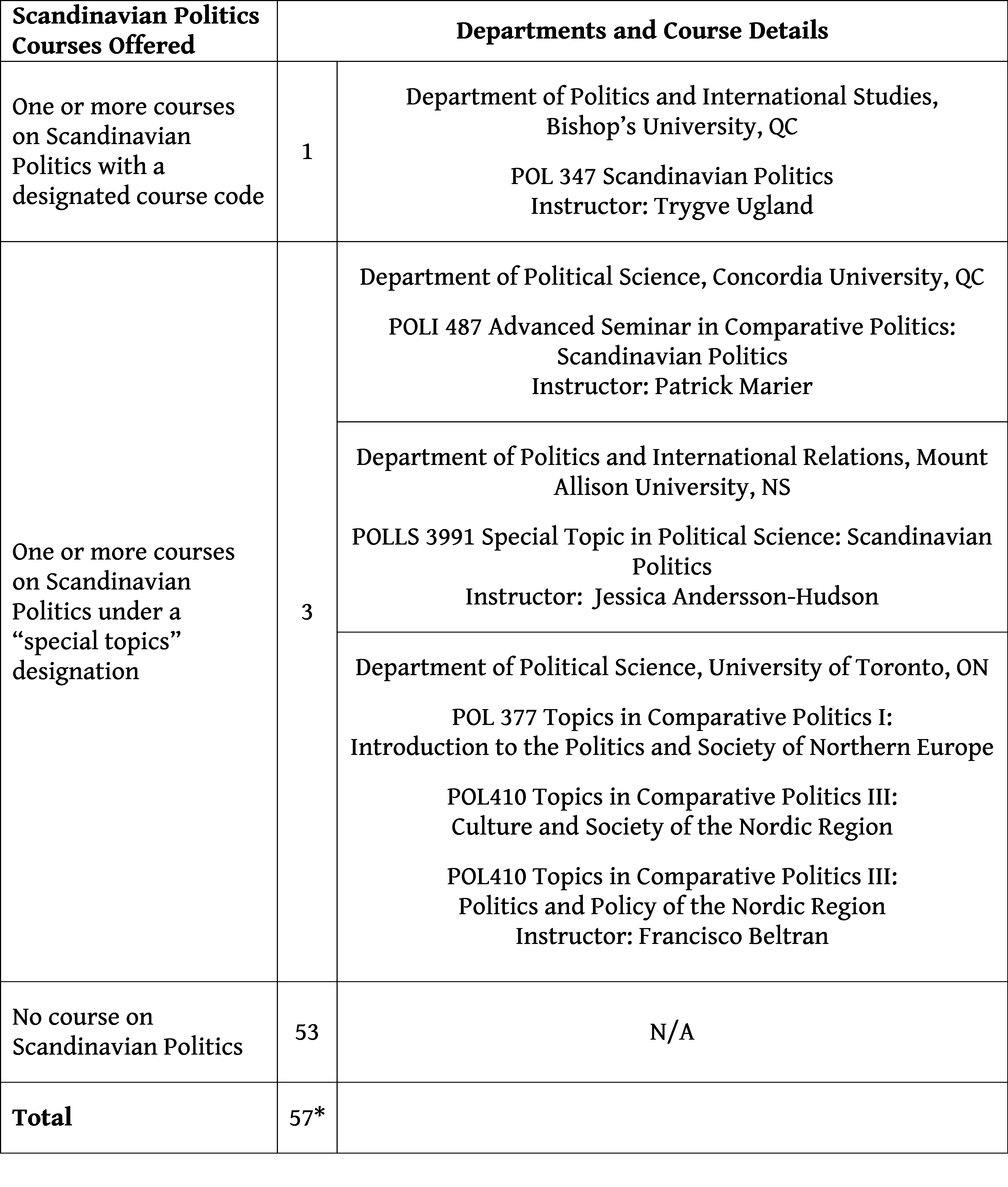

In 2022, a questionnaire was prepared and sent out to the chairpersons of the 57 affiliated departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA). Table 1 summarizes the response to the following questions: Has your institution offered any courses specifically on Scandinavian politics between 2018 and 2022? If so, how are these courses described and who teaches them?

Table 1. The teaching of Scandinavian Politics among the affiliated Departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA), 2018-22.

*There were 57 affiliated Departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA) in 2022. The response rate was 100%.

*There were 57 affiliated Departments of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA) in 2022. The response rate was 100%.

The tremendous interest in Scandinavia that we have witnessed in the world and in Canada during the past decade does not seems to be reflected in the offerings of Scandinavian politics courses in Canadian universities. The survey results reveal that only 4 universities (7% of the 57 institutions) had offered one or more courses dedicated solely to Scandinavian politics between 2018 and 2022 (Bishop’s University, Concordia University, Mount-Allison University, and the University of Toronto). Among the 4 universities, only Bishop’s University offered a course on Scandinavian Politics under a designated course code and description. In the three remaining cases, the courses were offered under the “special topics” designation, either as special topics courses in political science or in the subdiscipline of comparative politics. Furthermore, only at Bishop’s University and at Concordia University were the Scandinavian politics courses offered by full-time tenured faculty. Non-permanent sessional instructors taught the Scandinavian politics courses at Mount-Allison University and the University of Toronto.

Among the 53 universities that reported not to have offered any courses on Scandinavian politics during the 2018-2022 period, only one reported having done so prior to 2018.

Several of the respondents reported that Scandinavian content was integrated in other courses, most often in general comparative politics, or more specialized European politics courses. Nevertheless, there seems to be a mismatch between the attention paid to various aspects of the Scandinavian political model among academics and society more generally in Canada, and the very limited number of courses dedicated to Scandinavian politics at Canadian universities during the 2018-2022 period.

The limited contemporary attention to Scandinavian politics may partly be explained by the fact that “area studies,” i.e. the detailed examination of politics within a specific geographical setting, has come under increasing attack for various reasons within the sub-discipline of comparative politics and within the discipline of political science more generally during the past two decades (see for instance Basedau and Köllner). In particular, the relevance of area studies in an increasingly globalised world has been questioned. The main argument here is that globalization would diminish differences between the regions of the world and promote convergence and greater homogeneity in world politics. Area-studies have also often been criticized for lacking theoretical sophistication. Nevertheless, although that there are variations between countries, research indicates that political science departments continue to offer a wide range of area-specific courses (Briggs; Kwong and Wong).

The mismatch between attention paid to various aspects of the Scandinavian political model among academics and the limited attention to Scandinavian politics in the universities’ course offerings was also identified in the U.S. by Daniel J. O’Neil in the 1970s. Based on a survey of U.S. political scientists, O’Neil found that 10% of the respondents reported that their departments offered a course specifically on Scandinavian politics, while 70% of the respondents reported having a great or moderate amount of interest in Scandinavian politics. 15% reported having “attempted any publication on Scandinavian politics” (147).

In 1949, the American economist, Walter Galenson (1949: 1) argued that Scandinavia had become “a social laboratory” for other countries. However, the Scandinavian political model is often evoked by foreign politicians and policy practitioners in a highly superficial manner, more like a dominant image or symbol of success, rather than based on systematic and scientific analyses about the model’s appropriateness and suitability in a foreign context (Ugland 2014 and 2018). Scandinavia can still function like a laboratory for others. However, this will require systematic attention to the model in our universities. This can both be accomplished through dedicated courses on Scandinavian politics, but also through the integration of Scandinavian politics content into other courses in political science or outside the discipline. It will be argued that no matter which avenue is taken, a comparative and inter-disciplinary approach is likely to help promote Scandinavian politics content in university teaching.

Integrating Scandinavian Politics Content into other Courses

Due to limited available resources and departmental constraints, there is a long tradition of integrating Scandinavian politics content in other courses within the discipline of political science and more widely (see O’Neil). For instance, most textbooks on comparative and European politics will include references to individual Scandinavian countries and to Scandinavia more generally.

This section offers two recommendations on how to integrate Scandinavian content into other courses.

First, be comparative. While area studies have traditionally been recognized for their specific and rather exclusive focus on a single country or region, Basedau and Köllner highlights the advantages of comparative area studies of three types: intra-regional comparisons (comparing entities within an area); inter-regional comparisons (comparing different areas); and cross-regional comparisons (comparing entities from different areas) (110-111).

Applied on Scandinavian politics, comparative area studies can be conducted by comparing institutions and policies in the five Scandinavian countries (intra-regional comparisons), comparing institutions and policies in Scandinavia with institutions and policies in other areas (inter-regional comparison) and by comparing specific Scandinavian countries with countries in other areas. My own study of how Denmark, Norway and Sweden studied and learnt from Canada and the Canadian immigration and integration policy model combined all three types of comparative area studies (Ugland, 2014 and 2018).

In terms of teaching, it is assumed that the students will accumulate the most knowledge about Scandinavian politics by learning about similarities and differences between a) the Scandinavian countries; b) Scandinavia and other areas and regions; and c) specific Scandinavian countries and other countries.

Second, be inter-disciplinary. Scandinavian politics and Scandinavian studies more generally are interdisciplinary in nature and can complement and draw inspiration from other fields of study. In addition to comparative and European politics courses, Scandinavian politics content can also be integrated into courses in public policy and administration, political economy or international relations, as well as in courses outside the political science discipline, like in economics, education, environmental studies, history, criminology and sociology, to mention a few.

The range of perspectives provided should be exploited more effectively in university teaching by thinking interdisciplinary and collaboratively about Scandinavian politics. In addition to integrating Scandinavian politics content into different course, faculty members from various disciplines may also come to realisation that there is enough content to create a dedicated team-taught course on Scandinavian politics. An example of a comparative and interdisciplinary dedicated course on Scandinavian politics is provided below.

A Dedicated Course on Scandinavian Politics at Bishop’s University

Bishop’s University is a predominantly residential, mostly undergraduate liberal-arts university in Quebec, Canada, where programs are offered in fine arts, humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, business and education. In 2023, Bishop’s University had approximately 2,900 full-time students.

Since the 2003-04 academic year, I have taught an upper year undergraduate course on Scandinavian politics annually in the Department of Politics and International Studies. POL 347 Scandinavian Politics focuses on the political structures and processes in the Scandinavian or Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. While largely based on the comparative approach to the study of politics, POL 347 Scandinavian Politics also highlights special features in each Scandinavian country (intra-regional comparisons). Whenever relevant, the course also draws on comparisons between Scandinavia and Canada (inter-regional comparisons). The main learning objectives are to familiarize the students with Scandinavian politics, to enable them to understand important topics and debates as they relate to Scandinavian politics from a comparative perspective, and to prepare them for further studies in the politics of the Scandinavian countries.

In addition to being comparative in nature, the approach is also inter-disciplinary and touches on several sub-fields of political science and disciplines in social sciences. The course is divided in three sections:

1. Scandinavian democracy (with a focus on the Scandinavian political institutions, culture and behaviour)

2. Scandinavian welfare (with a focus on the Scandinavian political economies, public administration and social and welfare policies)

3. Scandinavia and the international dimension (with a focus on the Scandinavian nation-states’ relations with other nation-states, international organizations and trans-national actors and processes).

1. Scandinavian democracy (with a focus on the Scandinavian political institutions, culture and behaviour)

2. Scandinavian welfare (with a focus on the Scandinavian political economies, public administration and social and welfare policies)

3. Scandinavia and the international dimension (with a focus on the Scandinavian nation-states’ relations with other nation-states, international organizations and trans-national actors and processes).

In earlier surveys of Nordic or Scandinavian political studies, a lack of pertinent teaching materials and textbooks have been identified as a challenge (Askey, Gage and Rovinsky). This is certainly no longer the case. In addition to articles from relevant journals, there are several suitable textbooks for an introductory course on Scandinavian politics. During the 2003-2023 period, various editions of the following textbooks have been used:

-David Arter: Scandinavian Politics Today

-Eric S. Einhorn and and John Logue: Modern Welfare States: Scandinavian Politics and Policy in the Global Age

-Mary Hilson: The Nordic Model: Scandinavia Since 1945

-Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics

-David Arter: Scandinavian Politics Today

-Eric S. Einhorn and and John Logue: Modern Welfare States: Scandinavian Politics and Policy in the Global Age

-Mary Hilson: The Nordic Model: Scandinavia Since 1945

-Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics

Scandinavian Political Studies, which has been the leading journal on politics and public administration in the Scandinavian countries since 1966, is also an important resource. The journal covers all areas of political science with relevance for the politics of Scandinavian countries.

POL 347 Scandinavian Politics is offered annually, and in terms of enrollment, the course which is based on a hybrid lecture/seminar format is capped at 20 students, which seems to reflect the interest for the course at Bishop’s University, which has approximately 120 majors and honours students in Politics and International Studies. Based on the teaching evaluations from the students, the course is consistently ranked among the highest 10 % of all courses offered at Bishop’s in terms of broadening the students thinking about their field of study.

The Scandinavian-Canadian comparisons are crucial to the success of the course, and comparative term papers are often chosen by the students. Comparative work on the Scandinavian and Canadian welfare state regimes, their approaches to peace resolution in international relations, and various comparative public policy analyses have been popular. Inter-regional public policy comparisons between Canada and specific Scandinavian countries in the immigration, environment, oil and energy and education sectors are popular topics for term-papers. Recently, students have become increasingly interested in comparing Scandinavian and Canadian histories and policy approaches to Indigenous re-conciliation and de-colonialization.

Based on the experiences from Bishop’s University, the interest among students in a dedicated course specifically on Scandinavian politics is significant and enduring.

Conclusion

The Scandinavian model is currently under pressure due to important endogenous and exogenous challenges related to a sharp rise in immigration, increasing economic inequality and new regional security threats following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In light of these substantial challenges, the future sustainability of the Scandinavian political model can be questioned.

However, the Scandinavian countries have tackled grand challenges before, and the Scandinavian model has proven flexible and robust over time. The concept of policy learning is central here. Most often, the main message is that other countries can learn a lot from the policies of the Scandinavian countries. This is of course true. However, it can be argued that other countries can also learn a lot from how the Scandinavian countries learn from other countries. In fact, although this is a key to the success of the Nordic model, it is often a less appreciated element (see Ugland 2018). While policy learning from abroad often is described as a highly contested endeavor where political adversaries use foreign lessons selectively and strategically in the domestic debate, the Scandinavian countries’ approach to policy learning can be described as more deliberative, rationalistic, open and consensual. This approach to policy learning was apparent when the Scandinavian countries actively and systematically tried to learn from other countries, including Canada, in order to deal with the new challenges posed by increased immigration and ethnic diversity.

The approach to policy learning offers hope for the future of the Scandinavian political model, and it may also justify a continued and increased attention to Scandinavian politics in university teaching. Whether this attention comes in form of dedicated courses on Scandinavian politics, or through the integration of Scandinavian politics content into other courses, a comparative and interdisciplinary approach is recommended.

NOTES

- 'Scandinavia' is generally held to consist of the three nation-states of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Despite the overlapping histories and longstanding social and cultural ties with the three Scandinavian states, Finland and Iceland are commonly excluded in the definitions of Scandinavia. In the Scandinavian languages, the concept of ‘Norden’ is preferred as a reference to all five states. However, because Finnish and Icelandic politics and public policies resemble those of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in most areas, Finland and Iceland are often included in studies of the Scandinavian political model. This paper therefore includes all five states under the umbrella of Scandinavian politics.

- Despite the focus on Sweden, both Childs and Strode include many references to other Scandinavian countries and to Scandinavian politics more generally. For instance, Sweden: The Middle Way includes a separate chapter on the organization of farming in Denmark. In Sweden: Model for the World, Strode states: “So in this book when I say Swedish, the reader may in generalities be pleased to substitute the word Scandinavian” (xvii).

- For instance, both “Scandinavian Culture and Civilization (AUSCA 231)” and “Histoire des pays scandinaves (HIS22919)” that are taught regularly at the University of Alberta and at Université du Québec à Rimouski respectively, deal significantly with a number of political topics.

- The departments go under different names, and the complete list can be found on the website of the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA): https://cpsa-acsp.ca/affiliated-departments (Accessed 15 January 2022).

- For instance, Comparative Government and Politics: An introduction by Hague, Harrop and McCormick includes many references to Scandinavia as well as a particular spotlight on Sweden as one of 18 selected countries in the world.

REFERENCES

- Anton, Thomas J. 1969. “Policy-Making and Political Culture in Sweden.” Scandinavian Political Studies 4: 88–102.

- ———. 1980. Administered Politics: Elite Political Culture in Sweden. Boston, Massachusetts: Nijhoff.

- Arter, David. 2016. Scandinavian Politics Today. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Askey, Donald E., Gene G. Gage and Robert T. Rovinsky. 1975. “Nordic Area Studies in North America: A Survey and Directory of the Human and Material Resources.” Scandinavian Studies 47(2): 155-67.

- Barton, H. Arnold. 1968. “Historians of Scandinavia in the English-Speaking World Since 1945.” Scandinavian Studies 40(4): 273-293.

- Basedau, Matthias and Patrick Köllner. 2007. “Area Studies, Comparative Area Studies, and the Study of Politics: Context, Substance, and Methodological Challenges.” Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 1: 105–24.

- Booth, Michael. 2014. The Almost Nearly Perfect People: The Truth About the Nordic Miracle. New York: Picador.

- Briggs, Jacqui. 2016. “Political Science Teaching Across Europe.” PS: Political Science & Politics 49(4): 828–33.

- Bronner, Hedin and Gösta Franzen. 1967. “Scandinavian Studies in Institutions of Learning in the United States.” Scandinavian Studies 39(4): 345-67.

- Childs, Marquis. 1936. Sweden: The Middle Way. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Einhorn, Eric S., and John Logue. 2003. Modern Welfare States: Scandinavian Politics and Policy in the Global Age. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

- ———. 2010. “Can Welfare States Be Sustained in a Global Economy? Lessons from Scandinavia.” Political Science Quarterly 125(1): 1–29.

- Ekman, Ernst. 1965. “The Teaching of Scandinavian History in the United States.” Scandinavian Studies 37(3): 259-70.

- Gage, Gene. G. 1971: “Scandinavian Studies in America: The Social Science.” Scandinavian Studies 43(4): 414-36.

- Galenson, Walter. 1949. Labor in Norway. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hague, Rod, Martin Harrop and John McCormick. 2019. Comparative Government and Politics: An Introduction. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hancock, M. Donald. 1972. Sweden: The Politics of Post-industrial Change. Illinois: The Dryden Press.

- Heclo, Hugh. 1974. Modern Social Politics in Britain and Sweden. London: Yale University Press.

- Hilson, Mary. 2008. The Nordic Model: Scandinavia Since 1945. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

- Horváth, Dezsö, and Donald J. Daly. 1989. Small Countries in the World Economy: The Case of Sweden - What Can Canada Learn from the Swedish Experience. Halifax: The Institute for the Research on Public Policy.

- Kvavik, Robert B. 1982. “A Perspective on Scandinavian Studies in the United States.” Scandinavian Studies 54(1): 1–20.

- Kwong, Ying-ho and Mathew Y. H. Wong. 2022. “Teaching Political Science in the Age of Internationalisation: a Survey of Local and International Students.” Globalisation, Societies and Education: 1-11.

- Marier, Patrick. 2013. “A Swedish Welfare State in North America? The Creation and Expansion of the Saskatchewan Welfare State, 1944–1982”. Journal of Policy History 25(4): 614-37.

- Meixner, Esther C. 1941. The Teaching of the Scandinavian Languages and Literatures in the United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Milner, Henry. 1989. Sweden: Social Democracy in Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ———. 1994. Social Democracy and Rational Choice: The Scandinavian Experience and Beyond. London: Routledge.

- Nedergaard, Peter and Anders Wivel, eds. 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics. Oxon: Routledge.

- “The Next Supermodel.” The Economist, 2013. February 2nd Edition.

- O’Neil, Daniel J. 1973. “The Teaching of Scandinavian Politics in American Universities.” Scandinavian Studies 45(2): 144-51.

- Paquin, Stéphane, and Pier-Luc Lévesque, eds. 2014. Social-démocratie 2.0: le Québec comparé aux pays scandinaves. Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal.

- Paquin, Stéphane, Pier-Luc Lévesque and Jean-Patrick Brady, eds. 2016. Social-démocratie 2.1: le Québec comparé aux pays scandinaves. Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal.

- Partanen, Anu. 2016. The Nordic Theory of Everything: In Search of a Better Life. New York: Harper.

- Raynault, Marie-France, Dominique Côté, and Sébastien Chartrand. 2013. Le bon sens à la scandinave: politiques et inégalités sociales de santé. Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Strode, Hudson. 1949. Sweden: Model for a World. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- Ugland, Trygve. 2014. “Canada as an Inspirational Model: Reforming Scandinavian Immigration and Integration Policies.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 4(3): 144-52.

- ———. 2018. Policy Learning from Canada: Reforming Scandinavian Immigration and Integration Policies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Wiking, Meik. 2016. The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well. London: Penguin Books Ltd.