SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 29 (2022) pp.1-19.

DOI: 10.29173/scancan216

Copyright © The Author(s), first right of publishing Scan-Can, licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Title: Inuit Tattoos in Greenland Today: A Marker of Cultural Identity

Author:

Tukummeq Jensen Hansen

Tukummeq Jensen Hansen

Statement of responsibility:

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal:

Natalie Van Deusen, University of Alberta

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal:

Natalie Van Deusen, University of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus:

Katelin Parsons, University of Iceland

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus:

Katelin Parsons, University of Iceland

Statement of responsibility:

Production Editor/Directrice de la production:

Holly Pickering, University of Alberta

Production Editor/Directrice de la production:

Holly Pickering, University of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Translator/Traductrice:

Héloïse Torck, University of Alberta

Translator/Traductrice:

Héloïse Torck, University of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by:

Martin Holmes

Marked up by:

Martin Holmes

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal.

Source(s):

Hansen, Tukummeq Jensen. 2021.

Inuit Tattoos in Greenland Today: A Marker of Cultural Identity.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 29: 1-19.

Keywords:

- Greenland

- tattoo

- Inuit

- identity

- HP: added corrections to markup and additional information (bio, french abstract, page numbers) June 24, 2022

- MDH: entered author's proofing corrections 14th March 2022

- MDH: fixed missing commas 29th September 2021

- MDH: started markup 30th November 2020

Inuit Tattoos in Greenland Today: A Marker of Cultural Identity

Tukummeq Jensen Hansen

ABSTRACT: For years, Greenland has been under Danish colonial rule, which has left the Indigenous People of Greenland with trauma that still haunts them today. The search for identity that has left many young Inuit angry and confused has been difficult to express. Many young Inuit have chosen to use traditional tattoos to heal and strengthen themselves, to show that they are Inuit, to show that they are Kalaallit (Greenlanders). This phenomenon has been seen in Indigenous communities around the world who have experienced similar colonial violence. This essay focusses mainly on the young Inuit from Nuuk, but also discusses the Inuit from Nunavut.

RÉSUMÉ: Les années de domination coloniale danoise au Groënland ont causés des traumatismes qui hantent encore aujourd’hui les peuples autochtones du Groenland. La recherche d’identité qui a laissé de nombreux jeunes Inuits confus et en colère a été difficile à exprimer. De nombreux jeunes Inuits ont choisis d’utiliser les tatouages traditionnels pour guérir et renforcer leur sens d'eux-mêmes, pour montrer qu’ils sont Inuits, pour montrer qu’ils sont Kalaallit (Groenlandais). Ce phénomène a été observés à travers le monde dans les communautés autochtones qui ont expérimenté une violence coloniale similaire. Cet essai se concentre principalement sur les jeunes Inuits de Nuuk, mais parle également des Inuits de Nunavu.

Figure 1: Pani Enequist (right) and her husband, Sebastian Enequist (left), after

receiving their Inuit tattoos.

Photographer: Paninnguaq Lind Jensen.

A line on the chin that makes one more Greenlandic. Many young adults, especially women,

have been getting Inuit tattoos, whether on their face or on their body. This phenomenon

of young people bringing back a tradition that has been used in Greenland, Canada,

and Alaska is very new, but I doubt that it is for the same reasons that young people

get their faces and bodies tattooed as they did in the past. I have Inuit tattoos

myself, which is one of the reasons for my great interest in knowing what motivates

other people’s decisions to get tattoos. This article will try to answer the following

questions using interviews, a questionnaire, and informal conversations:

- Why did these young Greenlanders choose to have Inuit tattoos?

- Are these tattoos an expression of their Inuit identity?

- Has the colonization of Greenland been one of the reasons why some young people in Greenland have chosen to revive an old tattoo tradition?

- Who is allowed to have these tattoos?

My decision to get my own Inuit tattoos started with watching the documentary Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos (Arnaquq-Baril 2011). The documentary follows Alethea Arnaquq-Barilʼs quest to revitalize

her own cultural

heritage with a focus on Inuit tattoos. This moving documentary was a catalyst for

my choice to get my own Inuit tattoos. In addition to being one of the many young

people in Nuuk who has gotten Inuit tattoos, one also thinks as a researcher about

the reason others have for getting these tattoos.

The Longing for the Ancient Traditions

While looking at a Facebook page called Inuit Tattoo Traditions (Jacobsen and Jensen 2018), I found an emotional essay written by Inuit author Maya

Sialuk Jacobsen, who has

distinctive Inuit face tattoos. The essay is called “Ancestral threads” and starts

by discussing how Greenlanders have been told over and over again that

their language and way of life had no future and that they should be more civilized

and Danish. Maya used words like “Us” and “I” to show that she is a part of it as

she sees herself as Inuk. However, she does not

feel that she is just Greenlandic, but part of the entire Arctic Inuit population.

She herself grew up being assimilated into another culture, being brought up like

a Dane in Greenland. But she always knew that she was not Danish. She found a small

mask from the Dorset culture (see Figure 2), a migration of people to Greenland, before

the Thule culture. Maya herself says that she is a descendant of the Thule culture.

Figure 2 left: Jacobsen, Maya Sialuk, (2019) Ancestral Threads (Maskette, Devon Island,

Nunavut ca. 1900–1600 BC. Walrus ivory, 5.4 cm x 2.9 cm x 8 mm. Collection Canadian

Museum of History). Figure 2 right: Unknown title, Nordqvist, Jørgen et al. (1991,

103; ©Greenland National Museum).

A 3600-year-old mask had made Maya feel a sense of pride in her culture. Although

not a descendant of the Dorset culture, she could see a similarity between the Dorset

and the Thule culture, as the mask she talks about also had the same lines on her

face as the 500-year-old Qilakitsoq mummies also have (see Figure 2 right). She even

thought that this mask had exactly the same lines as Inuit women today have: “Her

chin lines are exactly the same as the lines I tattoo on Inuit women today: precise

straight lines from lip to chin that mark childhoodʼs end” (Jacobsen 2019).

Mayaʼs tale of the pride of having reinvented her culture is also the same tale Alethea

Arnaquq-Baril has to tell (Arnaquq-Baril 2011). The woman behind the documentary

Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattooing comes from Iqaluit, Nunavut. She says that for a long time she has been fascinated

with Inuit tattoos after seeing a picture of an Inuk woman with tattoos on her face.

Her first thoughts were whether this woman was a shaman, whether she was wise and

powerful. She wanted to know more about what the tattoos had been used for, how the

tattoos once looked, what her people had been through, and why the tattoos disappeared.

At the end of the documentary she eventually has them placed on her own face and arms.

Both Maya and Alethea have been homesick and longing for their culture while outside

their motherland. In her article, Maya says that for 10 years she has travelled around

as a Western tattoo artist, while Alethea has been away from her home country for

12 years to study. Alethea tells in the documentary that she herself thinks she has

missed out on a lot (from her own culture). She states: “I’m 27 and I’ve never sewn

my own parka. I’m clumsy at sharpening my ulo blade. I

don’t know how to butcher and prepare seal meat. These are the most basic skills of

a woman my age.” She follows up with: “I feel like there is a huge hole in my heart

and I need to fill it with this knowledge” (Arnaquq-Baril 2011). She believes that

every time she learns a new skill that an Inuk woman should be

able to have, a small part of her is healing. According to Thomas Hylland Eriksen,

this is a reaction to a conflict between the Indigenous People and the modern western

countries. He explains that the Indigenous Peoples have “… organisert seg gjennom

transnasjonale organisasjoner og nettverk for å beskytte

sine rettigheter til forfedres land og sine kulturelle tradisjoner” [organized themselves

through transnational organizations and networks to protect their

rights for the land of their ancestors and cultural traditions] (Hylland Eriksen 276). Looking back on history, for both Greenland and Canada, both countries have experienced

being converted from their own faith to Christianity. Both women who have an ethnic

background with a common history of being converted from their “original” way of life

to a western “modern” way of life feel that they have an urge to cultivate their “traditional”

habits. Their encounter with the Western homogenized world has given them the desire

to revitalize their own cultural heritage.

Inuit tattoos on Facebook and Other Social Media

Inuit tattoos have started to become very visible on social media, especially on Facebook,

where Maya Sialuk Jacobsen and Paninnguaq Lind Jensen have created a page to inform

people about Inuit tattoos. Paninnguaq Lind Jensen is a young tattoo artist from Greenland

who is undergoing training to become a traditional tattoo artist, bearing visible

Inuit facial tattoos. The first thing you notice is a post they have placed at the

top of the page that asks visitors of the site to respect “our patterns and traditions”.

The site is primarily in English, however, when you look at the first entry on the

Facebook page, it is in Danish, while some of the entries are in Greenlandic. In their

“About” section, you can read about who both Maya and Paninnguaq are, and this information

is written in English and Greenlandic only. It could be interpreted as having tried

as much as possible to avoid writing in Danish, because of the colonization of Greenland

by Denmark.

The site has many pictures that exhibit Inuit tattoos, and at first glance there are

many pictures of women with Inuit tattoos. Historically, Inuit tattoos have been reserved

primarily for women. In the documentary Tunniit, an older woman by the name of Annie Paingut Peterloosie and her husband comment

that you were not a real woman if you did not have any Inuit tattoos. A woman would

get these tattoos once she learned the important skills that Alethea talked about

earlier. The tattoos symbolized that she was ready to start a family. However, these

days it is not just women who have had facial tattoos. The Facebook page also shows

men who have been tattooed on the chin, but they are not the same as the women. A

post can be read on their Facebook page, which explains exactly how menʼs tattoos

worked in the past. A manʼs tattoo was a form of amulet to protect them or served

as event markers if a taboo had been broken. An anonymous informant thought it was

“a little strange” that some men choose to have tattoos on their chin, since they

had heard that the

chin tattoos were primarily for women.

Taboo is a big part of the Inuit religion, which they especially talk about in the

documentary Tunniit. A French-Canadian ethnographer, Bernard Saladin DʼAnglure, has interviewed one of

the last tattooed women from Aletheaʼs homeland. She explains that it was believed

that womenʼs menstruation blood would cause bad luck for the hunt, so the tattoos

were used as a cleansing ritual when a young woman would have her first period. While

researching further on the Facebook page, I found a DR (Danmarkʼs Radio) article from

April 23, 2018 (Sæhl et al. 2018), that is about Greenlanders, primarily in Nuuk,

who had begun to get Inuit tattoos.

A video had also been posted along with the article, where two young Greenlanders

explain why they got their tattoos. The first was a young Greenlandic woman with a

tattoo on her chin. She states the following in Danish: “Jeg har fået min tatovering

for at tydeliggøre min grønlandsk identitet” [I got this tattoo to make clear that

I have a Greenlandic identity] (Sæhl et al. 2018). A young Greenlandic man named Sebastian

Enequist, who also has a tattoo on his chin,

goes on to explain in Greenlandic: “Qallunaanngorsaanerput naammaleqaaq. Kakiornera

aqqutigalugu nunara utertikkusuppara” [I have had enough of living like a Dane. I

will take my country back through my tattoos] (Sæhl et al. 2018). Maya Sialuk Jacobsen

is also featured in the video where she says that the tattoos

are a very significant way to take one’s face back after a long period living under

colonization.

I interviewed a young Greenlandic woman named Pani Enequist (Figure 1). I asked her

about her reasoning for getting her Inuit tattoos. She says that, while growing up,

she had not been told anything about how the Danes took the traditions from the Inuit

Peoples and replaced them with Christian values. When she found out, her heart was

broken. She had interviewed Maya (Sialuk Jacobsen) about Inuit tattoos, where Mayaʼs

stories had touched her greatly. Pani explains: “I decided to get my marking because

I wanted to honour our old traditions and our

people.” Paniʼs explanation regarding her choice to have Inuit tattoos is related

to Maya

and Aletheaʼs story of how one has the feeling of being deprived of one’s indigenous

Inuit traditions, which is very much related to one’s identity. They have chosen to

use the tattoos as an identity marker, which has “taken their faces back,” as Maya

Sialuk Jacobsen explained earlier.

Other Peopleʼs Opinions

But what do other people think about revitalizing an old tattoo tradition? An anonymous

informant believed that it was about dignity and identity and that it was a personal

decision people make about getting tattoos. The informant thought it was “a kind of

courageous decision” that one makes when getting a face tattoo, since the face is

the first thing you

notice about a human being. Another opinion we heard was from an elderly Greenlandic

lady living in Denmark. She thought the tattoos were ugly and that it is not a good

way to show one’s Greenlandic identity, as she herself thinks that there are other

ways to show Greenlandic identity, such as having tupilaq figures on display at home. However, a third informant, an elderly lady living in

Nuuk, asserts that she is proud of the young people who choose to keep old traditions

alive.

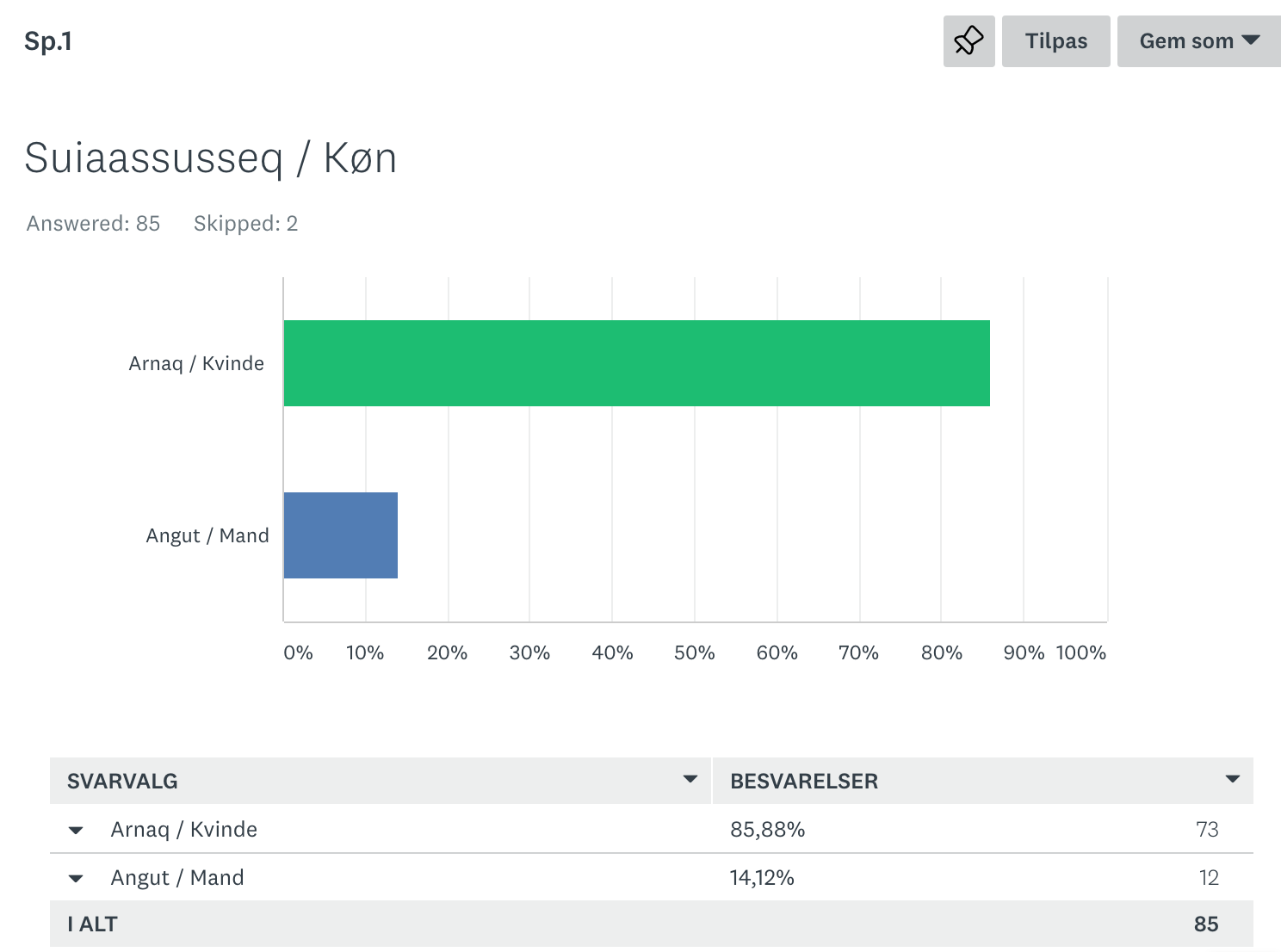

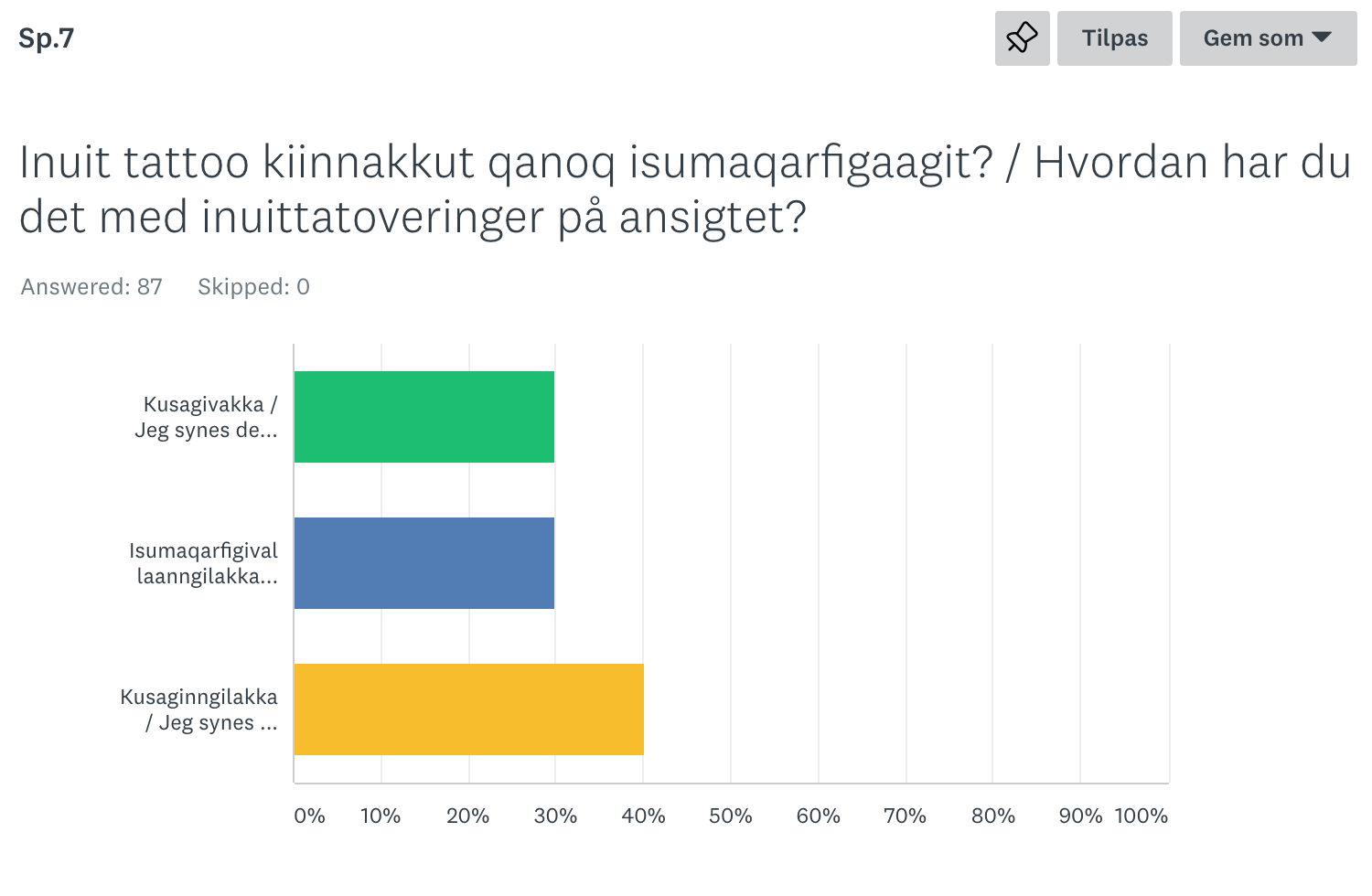

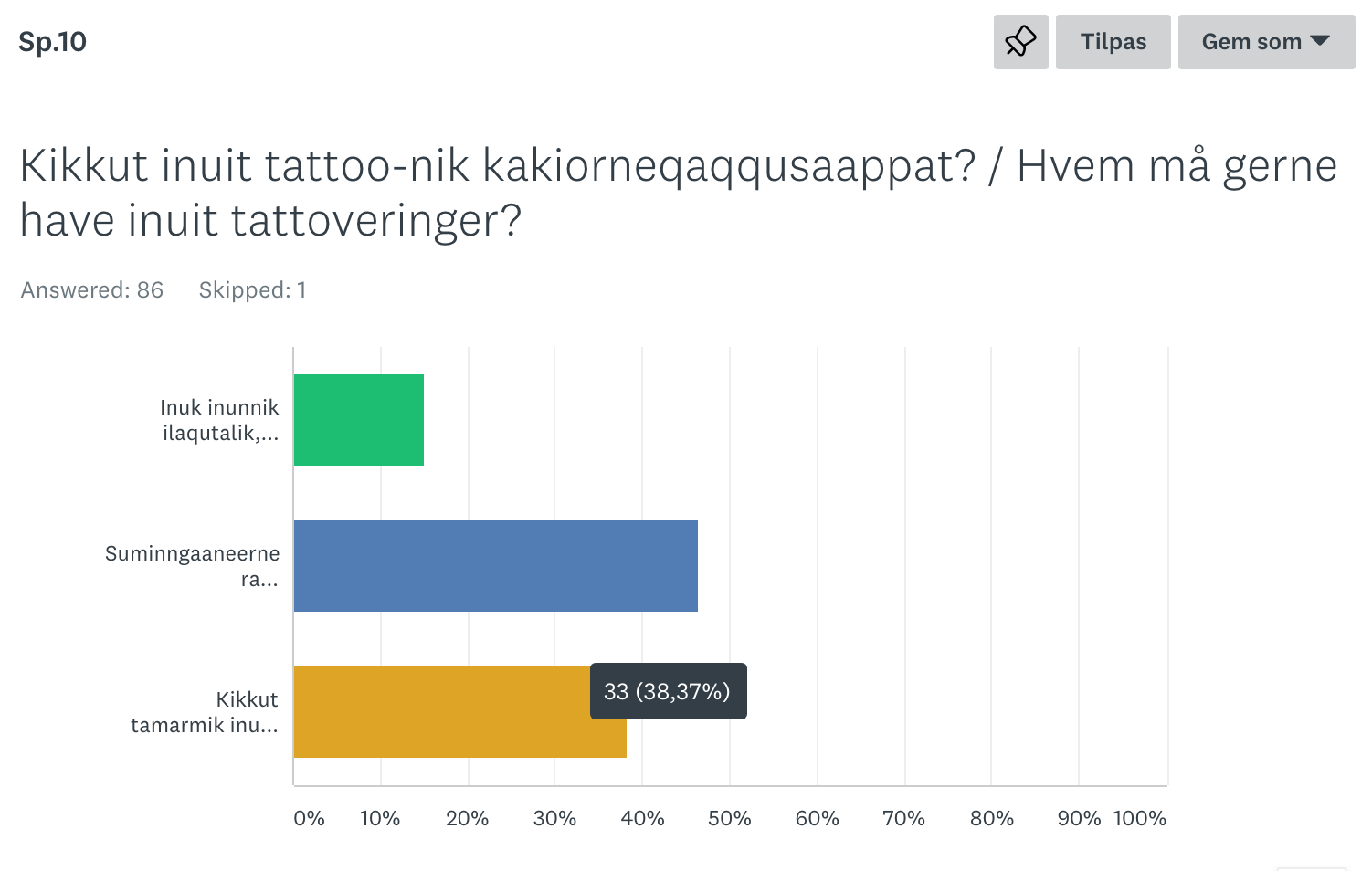

The questionnaire survey carried out as part of this research project (Appendix) shows

that 46.51% of the participants believe that one must be associated with Greenlandic

culture before one can have Inuit tattoos, whereas only 15.12% think that one must

be born and raised in Greenland. 38.37% contend that everyone was allowed to have

Inuit tattoos. Even though most people who answered the questionnaire believe that

you must be associated with Greenlandic culture before one can have Inuit tattoos,

it can be a cause for concern to know that as many as 38,37% believe that everyone

is allowed to have Inuit tattoos. The reason I find this troubling is that cultural

appreciation can easily become cultural appropriation. This is a very difficult subject,

considering that so many Indigenous people receive these tattoos to heal from the

trauma caused by colonization. This issue was also discussed in an informal conversation

with Kamilla Østergaard Madsen, a psychology student, and Louisa Høyer, a certified

tourist guide, who were both born and raised in Greenland. Louisa thought that the

tattoos are great, and she has even considered getting one herself, as she has experienced

that tourists do not believe that she is Greenlandic, as she does not look typically

Greenlandic. However, she asserts that those who get these tattoos must be at least

born and raised in Greenland, be integrated into the Greenlandic community, have a

Greenlandic name and be able to speak Greenlandic. Kamilla believes that having a

tattoo is a realization of cultural identity, especially since Greenland has experienced

colonization. Kamilla says that Greenland is a rich culture that has been cornered,

as Greenland is still part of the Rigsfællesskab (the Danish Realm). In order to create

a contrast between the Danish and the Greenlandic, one has chosen to reinforce oneʼs

identity by getting Inuit tattoos. However, Kamilla thinks it is quite controversial,

as she believes that you could end up having problems with being hired into larger

companies with facial tattoos. Nuuk is a city with the largest foreign population

compared to other cities in Greenland, and locals are often bilingual or speak only

Danish. Thomas Hylland Eriksen comments that “Revitalisering er nesten alltid en reaksjon

på modernisering og tiltagende kulturell

homogenisering, og vil i en viss forstand gjenskabe den ‘tradisjonelle’ kulturen på

den ‘moderne’ måte” [Revitalization is almost always a reaction to modernization and

increasing cultural

homogenization, and the revitalization will in some way revive the “traditional” culture

in a modern way] (Hylland Eriksen 277). The reason could be that young people have

chosen to take up the Inuit tattoo tradition

with a modern relevant meaning, in order to distinguish between the Greenlandic and

the Danish.

The various sources are consistent with each other, and they suggest that todayʼs

young people in Greenland have chosen to have these tattoos made in order to mark

their Greenlandic identity. Inuit tattoos represented something else in the past (for

example, a woman would get these tattoos once she learned the important skills a woman

should have to start her own family), but these representations are still kept close

as a memory of the past meaning of the tattoos. These memories are then chosen to

be honoured, by getting the Inuit tattoos oneʼs ancestors once had. However, the question

of who is allowed to get these tattoos can be controversial, as some believe that

one needs to be associated with the Greenlandic culture while others believe that

it does not matter. These tattoos have clearly become a way of expressing the trauma

that colonization has brought to Greenland and its people.

Notes

Participants were allowed to have their full name used in this essay, and names that

are freely promoted in social media and documentaries have also been used. Three out

of five who participated in informal conversations were kept anonymous. The author

herself has Inuit tattoos, which could have caused bias during the fieldwork as well

as writing this article, however, the author has tried to stay as neutral as possible.

It is, however, still possible to have bias when you have an interest in the subject,

even if you do not have Inuit tattoos. The questionnaire was made through surveymonkey.com

and was the author’s first time trying it out with a fellow student. It was distributed

through two personal Facebook accounts, where the majority of the answers came from

Greenlanders. The data received at the end of the trial (of the questionnaire) might

have some flaws, but the data is still considered valid information. The questionnaire

could have been more refined, such as giving the informant the possibility to supply

more in-depth responses, but the author had a limited amount of time to do this research,

considering the paper was originally an exam report in the first year of a Bachelor

of Education program.

NOTES

- All translations, unless otherwise indicated, are my own.

- In Greenland a tupilaq (plural tupilliat) is a physical representation through which supernatural misfortune was passed, carved from animal bones. Today tupilliat objects, figurines, or statues are among Greenland’s most popular carved souvenirs and were historically given as souvenirs to ethnographers or whalers (Nuttall 2004, 2075).

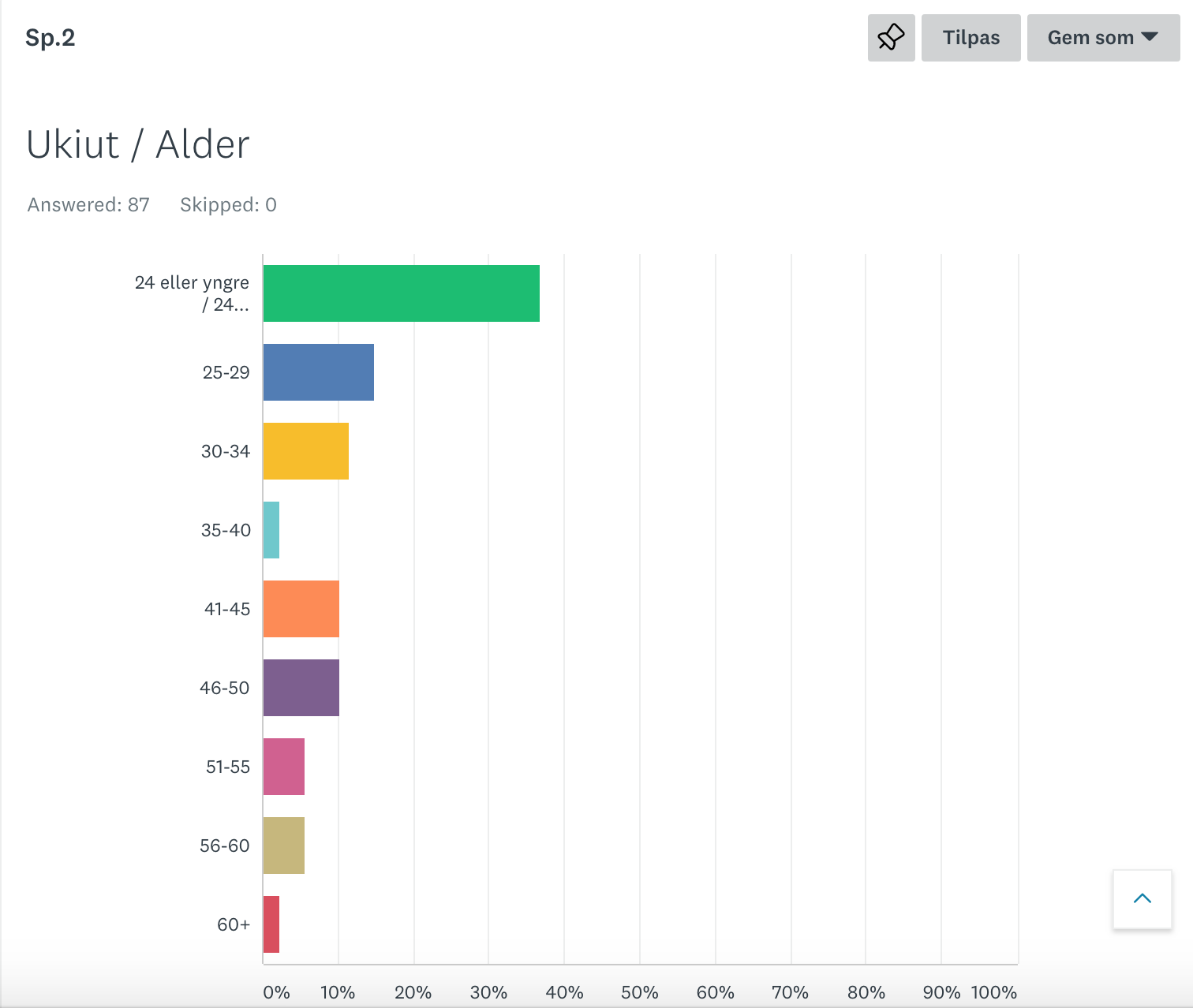

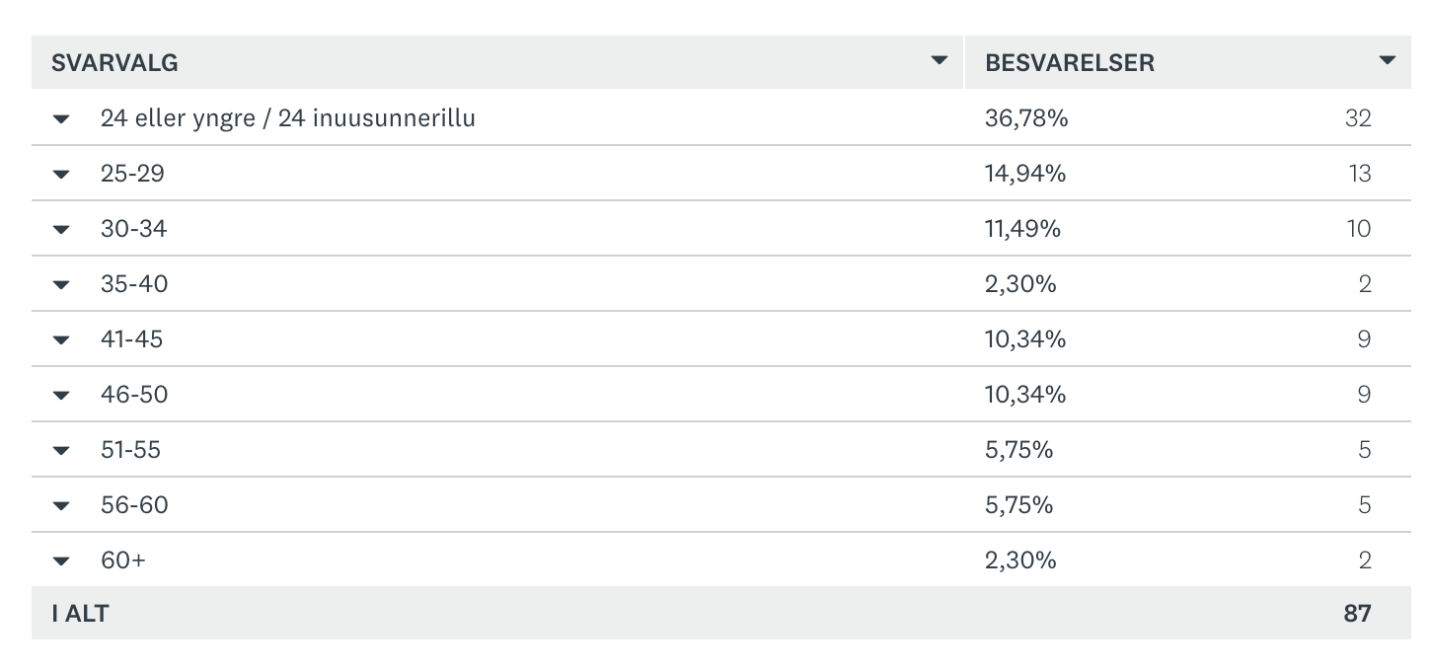

APPENDIX

Questionnaire answered (Available from 10 May 2019 - 20 June 2019). Made at Survey Monkey, Website: https://da.surveymonkey.com

Gender:

Women 85.88%

Men 14.12%

Men 14.12%

Total 85

Age

24 or younger (the rest is just the other ages)

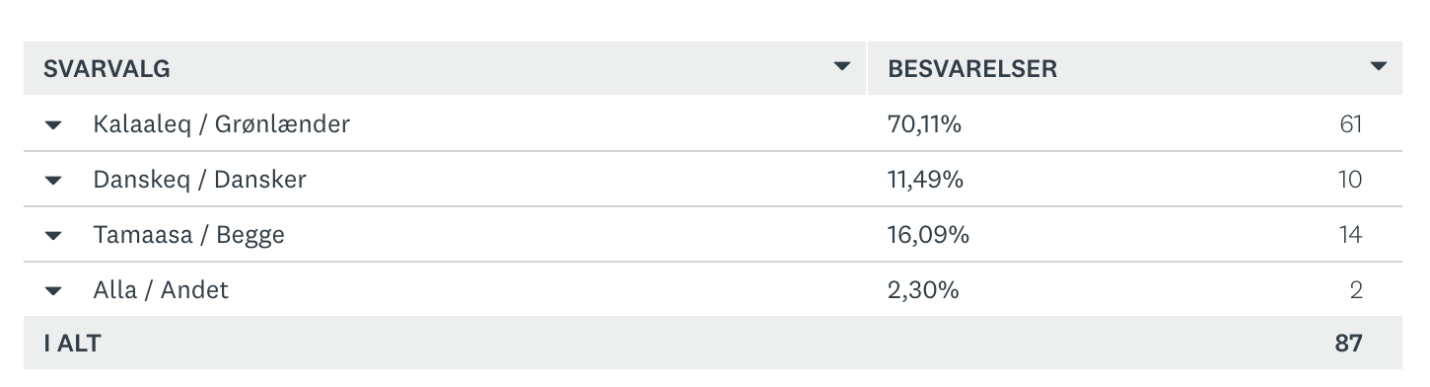

Nationality

Greenlander 70.11%

Dane 11.49%

Both 16.09%

Other 2.30%

Dane 11.49%

Both 16.09%

Other 2.30%

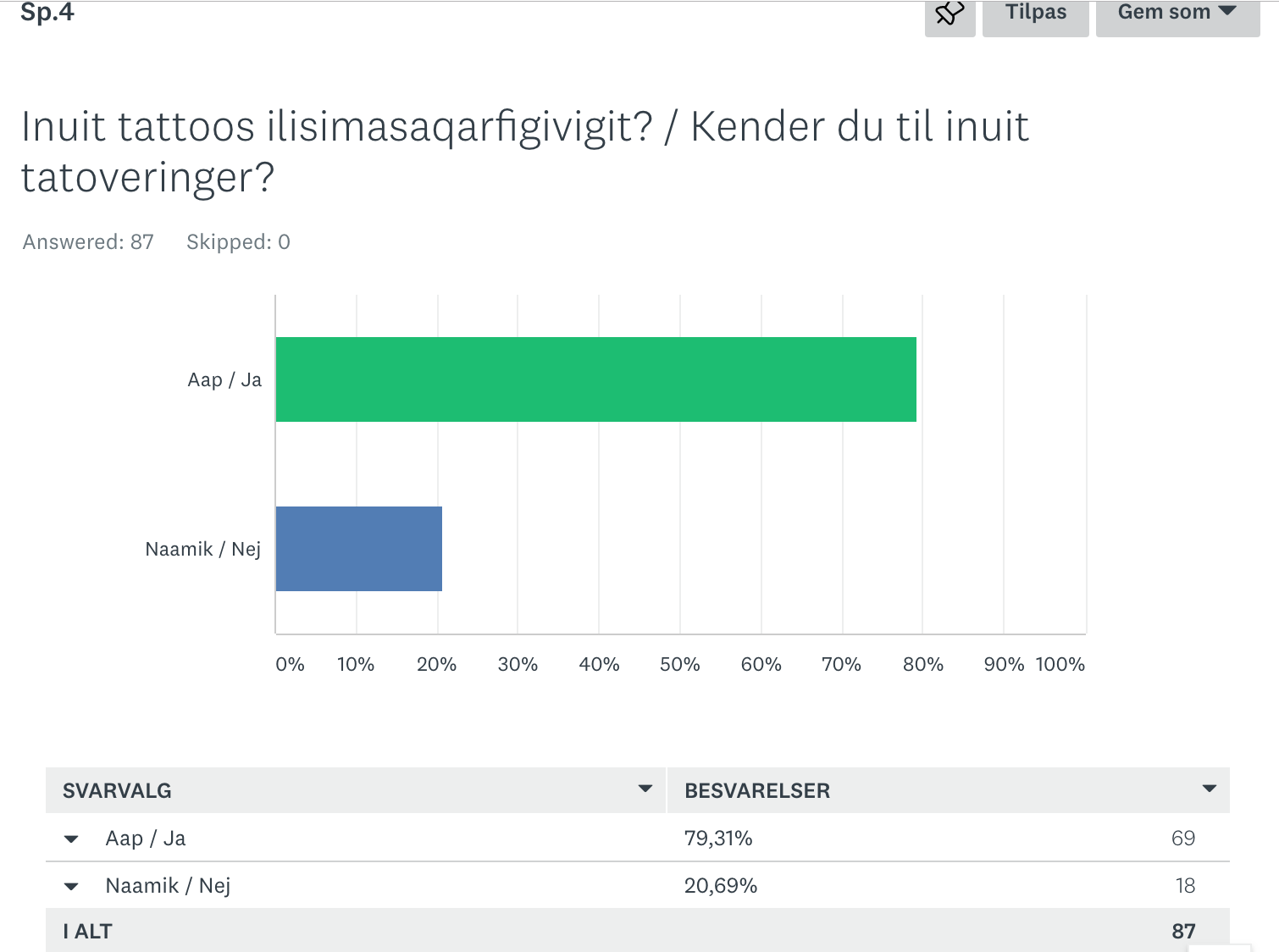

Do you have knowledge about Inuit tattoos?

Yes 79.31%

No 20.69%

No 20.69%

Do you have Inuit tattoos?

Yes 4.60%

No 95.40%

No 95.40%

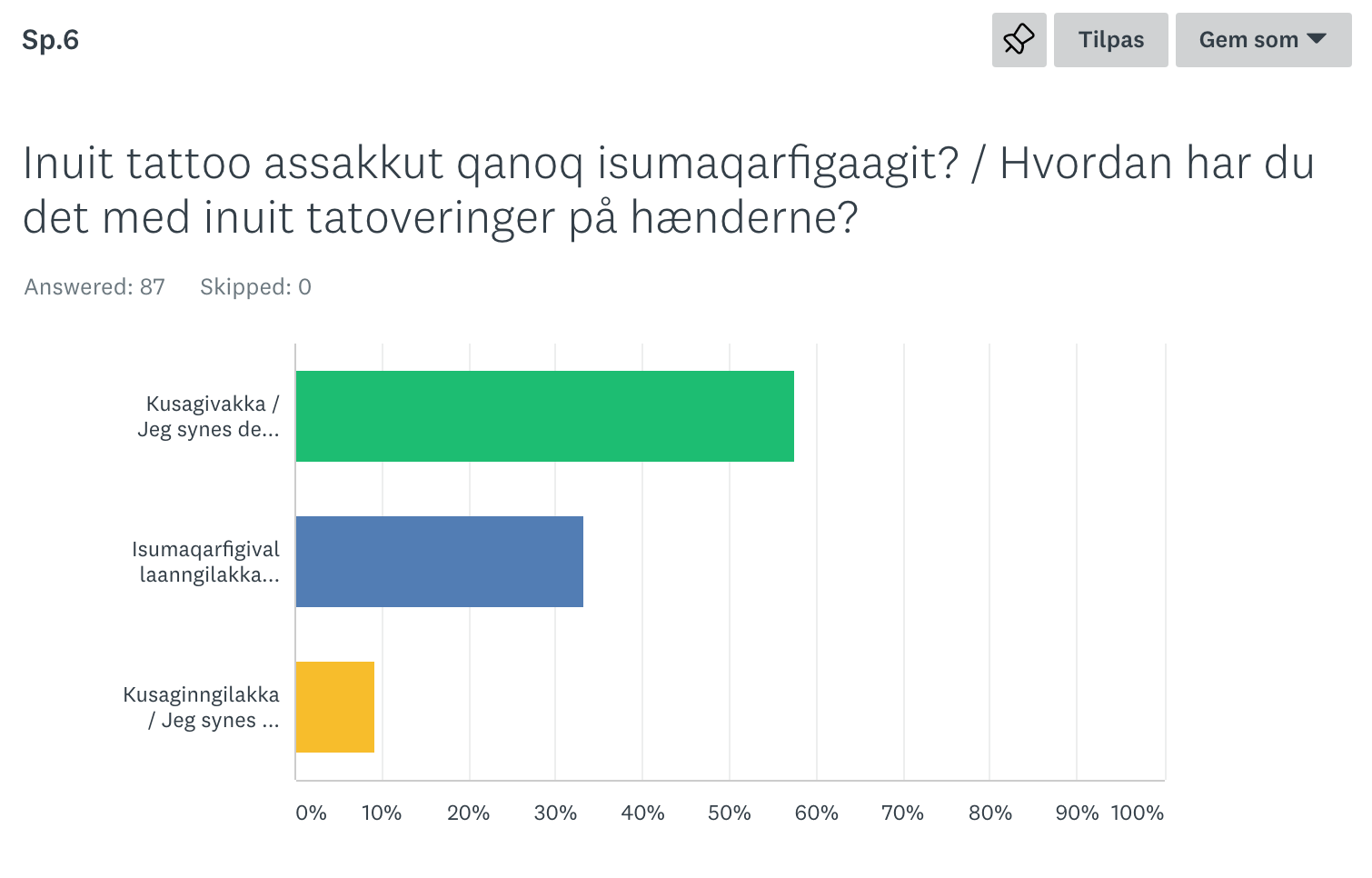

What do you feel about Inuit tattoos on the hands?

I think they are beautiful 57.47%

Neutral 33.33%

I think they are ugly 9.20%

Neutral 33.33%

I think they are ugly 9.20%

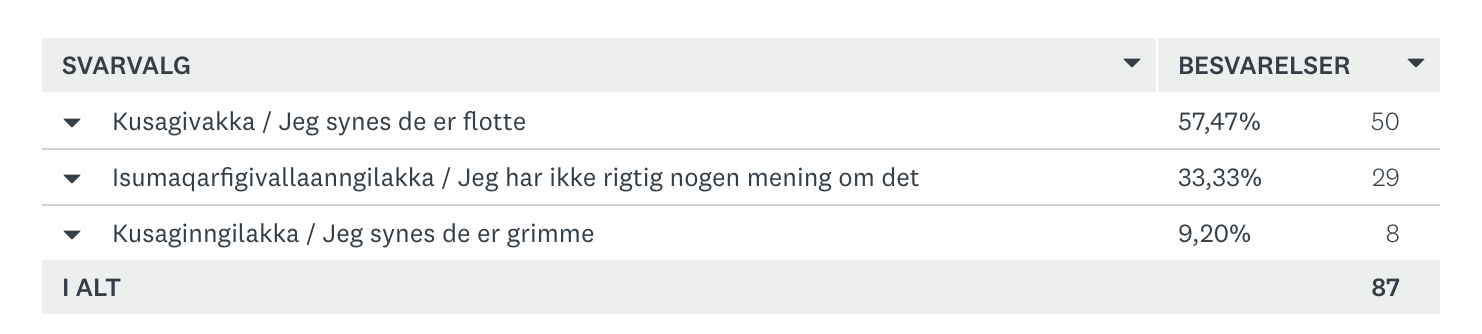

What do you feel about Inuit tattoos on the face?

I think they are beautiful 29.89%

Neutral 29.89%

I think they are ugly 40.23%

Neutral 29.89%

I think they are ugly 40.23%

Do you agree with this statement?

“I think Inuit tattoos are a good way to revive old traditions.”

Do you agree with this statement?

“I think Inuit tattoos are a good way to show ones Greenlandic identity.”

Who is allowed to have Inuit tattoos?

A person of Inuit descent, who considers themselves Inuk 15.12%

Their ancestry does not matter, as long as they consider themselves as a part of the Inuit culture 46.51%

It does not matter; anyone can get Inuit tattoos 38.37%

Their ancestry does not matter, as long as they consider themselves as a part of the Inuit culture 46.51%

It does not matter; anyone can get Inuit tattoos 38.37%

REFERENCES

- Arnaquq-Baril, Alethea. 2011. Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattooing. Film. Directed by Alethea Arnaquq-Baril. Iqualuit: Unikkaat Studios, 2011.

- Eriksen, Thomas H. 2010. Små steder – Store spørgsmål. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Estes, Larry, and Scott Rosenfelt. 1998. Smoke Signals. DVD. Directed by Chris Eyre. Toronto: eOne, 2000.

- Hart Hansen, Jens Peder, Jørgen Meldgaard, and Jørgen Nordqvist. 1991. The Greenland Mummies. Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers’ Forlag.

- Jacobsen, Maya Sialuk. 2019. “Ancestral Threads.” Canadian Art, Essays, March 18, 2019. Accessed 7 January 2020. https://canadianart.ca/essays/ancestral–threads/.

- Jacobsen, Maya Sialuk, and Paninnguaq Lind Jensen. 2018. “Inuit Tattoo Traditions.” Facebook page (public). Accessed 8 January 2020. https://www.facebook.com/inuittattootraditions/.

- Nuttall, Mark, ed. 2004. Encyclopedia of the Arctic. New York: Routledge.

- Sæhl Marie, Thøger Kirk, and Bardur Vejhe. 2018. “Grønlændere bliver tatoveret i ansiget: Vi tager vores identitet tilbage.” Valg i Grønland. Online video. DR (formerly Danmarks Radio), April 23, 2018. Accessed 7 January 2020. https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/valgigroenland/video–groenlaendere-bliver-tatoveret-i-ansigtet-vi-tager-vores.