SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 28 (2021) pp.144-177.

Title: ein lǫg ok einn siðr: Law, Religion, and their Role in the Cultivation of Cultural Memory in Pre-Christian Icelandic Society

Author: Simon Nygaard

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Statement of responsibility:

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Guest Editors/Rédacteurs invités

Yoav Tirosh CVM (Center for Vikingetid og Middelalder) at Aarhus University

Guest Editors/Rédacteurs invités

Yoav Tirosh CVM (Center for Vikingetid og Middelalder) at Aarhus University

Statement of responsibility:

Guest Editors/Rédacteurs invités

Simon Nygaard Aarhus University, Denmark

Guest Editors/Rédacteurs invités

Simon Nygaard Aarhus University, Denmark

Statement of responsibility:

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Natalie M. Van DeusenUniversity of Alberta

Book Review Editor/Rédactrice des comptes rendus

Natalie M. Van DeusenUniversity of Alberta

Statement of responsibility:

Technical Editor

Martin Holmes University of Victoria

Technical Editor

Martin Holmes University of Victoria

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Journal

Source(s):

Nygaard, Simon. 2021.

ein lǫg ok einn siðr: Law, Religion, and their Role in the Cultivation of Cultural Memory in Pre-Christian Icelandic Society.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 28: 144-177.

Languages used in the text:

- German (ny_de)

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- cultural memory

- Íslendingabók

- Assmann, Jan

- law speaker

- law

- lǫgsǫgumaðr

- Weber, Max

- oral transmission

- religion

- ritual

- Rappaport, Roy A.

- Úlfljótslǫg

- value spheres

- MDH: sort order of reference list tweaked per editors 26th October 2021

- MDH: entered more editors' proofing corrections 13th October 2021

- MDH: entered author's and editor's proofing corrections 12th October 2021

- MDH: entered author's and editor's proofing corrections 16th September 2021

- MDH: entered French abstract 23rd August 2021

- MDH: entered new author bio info from editors 7th June 2021

- MDH: finished first encoding pass 25th August 2020

- MDH: started markup 24th August 2020

ein lǫg ok einn siðr: Law, Religion, and their Role in the Cultivation of Cultural Memory in Pre-Christian Icelandic Society

Simon Nygaard

ABSTRACT: The transmission of law in pre-Christian Iceland was an oral process in

an oral society. In oral societies, such transmission processes may be characterized

as a cultivation of cultural memory, which suggests that it was transmitted through

a ritualized performance by a memory specialist. In the Icelandic context, this specialist

was in all likelihood the lǫgsǫgumaðr. However, the connection between the transmission of law by the lǫgsǫgumaðr and ritual

and religion has not yet been established explicitly. This is the subject of the present

article, which first views the intricate relationship between law and religion in

pre-Christian Iceland through the lens of Max Weber’s theory of value spheres and

subsequently treats the transmission of early Icelandic law as a cultivation of cultural

memory.

RÉSUMÉ : La transmission du droit au sein de l’Islande préchrétienne était un processus

oral dans une société orale. Dans les sociétés orales, de tels processus de transmission

peuvent être caractérisés comme une culture de la mémoire culturelle, ce qui suggère

qu’elle était transmise par la représentation ritualisée d’un spécialiste de la mémoire.

Dans le contexte islandais, ce spécialiste était selon toute vraisemblance le lǫgsǫgumaðr. Toutefois, le lien entre la transmission du droit par le lǫgsǫgumaðr, le rituel

et la religion n’a pas encore été établi explicitement. C’est l’objet du présent article,

qui envisage d’abord la relation complexe entre le droit et la religion au sein de

l’Islande préchrétienne, à travers le prisme de la théorie des sphères de valeur (rapports

aux valeurs) de Max Weber, puis traite ensuite de la transmission du droit islandais

ancien comme une culture de la mémoire culturelle.

The transmission of law in pre-literate Iceland has often been viewed as a secular

phenomenon, where the orally-trained lǫgsǫgumaðr [lawspeaker], as the spokesperson of the Icelandic lǫgrétta [Law Council], relied on their traditional legal knowledge in the prosecution of

cases and recitation

of law (G. Sigurðsson 2004; Kjartansson). The role of the lǫgsǫgumaðr in pre-Conversion

and pre-literate Iceland as it is

described in the legal code Grágás in particular, as well as the Íslendingasǫgur, has been viewed as being a secular affair. Not until the movement towards an affiliation

of the lǫgsǫgumenn with the Church in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is the religious sphere thought

to have become a deciding factor (see G. Sigurðsson 2004). Nonetheless, several factors

seem to indicate that this division between the religious

and the secular might not be as clear-cut as previously suggested—especially in tenth

century, pre-Christian Iceland and the North in general (Schjødt 2020a).

The little evidence we have of legal practice connected to the late Viking Age seems

to point firmly in the direction of a connection between the Weberian value spheres (Weber [1920] 1986a) of the religious and the secular, of religion and law (see also

Brink 2003, 2020). Furthermore, while our sources are of course written, it is commonly

assumed that early Nordic laws were orally transmitted for an extended period of time

(Strauch 2011, 3). This is also the case with the earliest Icelandic written examples

of legal material.

In essence, the legal code Grágás is a literary product. The medieval manuscripts that contain the earliest versions

of Grágás are products of a medieval, Christian, Icelandic scribal tradition since both main

manuscripts were produced in the latter half of the thirteenth century (Dennis, Foote,

and Perkins 1980, 13–14). Some parts of Grágás, however, betray traits of orality at various levels, like the more or less obvious

orality of the spoken, early medieval legal procedures (McGlynn), but some instances

may reflect connections to an earlier oral, legal tradition (Brink 2008, 25-28; 2011;

2015, 7-8; Foote 1977a, 1977b, 1987). This is also the case with early Swedish legal

material (Brink 2011) as well as Norwegian examples (Strauch 2011, 109–212).

The transmission of legal material between the earliest known instances of Icelandic

legal material, the semi-mythic Úlfljótslǫg, and the assumed initial codification of law known as Hafliðaskrá in the winter of 1117/1118 (Íslendingabók ch. 10) was thus an oral process in an oral society (Foote 1977a; Kjartansson).

In oral societies, such transmission processes may be characterized as a cultivation

of cultural memory (J. Assmann 2008), which in turn gives us an idea of how the transmission

may have taken place: through

a ritualized performance by a memory specialist (J. Assmann 2006, 39–40; 2008, 114–18;

Nygaard and Schjødt). In the Icelandic context, this specialist was in all likelihood

the lǫgsǫgumaðr,

as has been pointed out by scholars in the past (for instance, Brink 2014; G. Sigurðsson

2018). However, the connection between their recitation of law (see Grágás K20) and ritual and religion has not yet been established explicitly. This will be

the

subject of the present article, which will look first at the connection between law

and religion in pre-Christian Iceland and then at the transmission of the early law

as a cultivation of cultural memory.

The Connection between Law and Religion in the pre-Christian North

Traditionally, the realms of religion on the one hand, and law, politics, and art

on the other, are set apart and dealt with more or less separately by scholars of

the pre-Christian North. This may seem unproblematic, since these topics are indeed understood as separate

in modern-day society, and accordingly scholars classify themselves, for instance,

as either historians of religion or legal historians. Consequently, our sources are seen as sources for either religion or law as well, as representing either the religious or the secular. Many of these sources, however, do not seem to fit so neatly into either category.

From the perspective of the study of religion, this may in fact not be a surprise

or a problem (see also Schjødt 2020a).

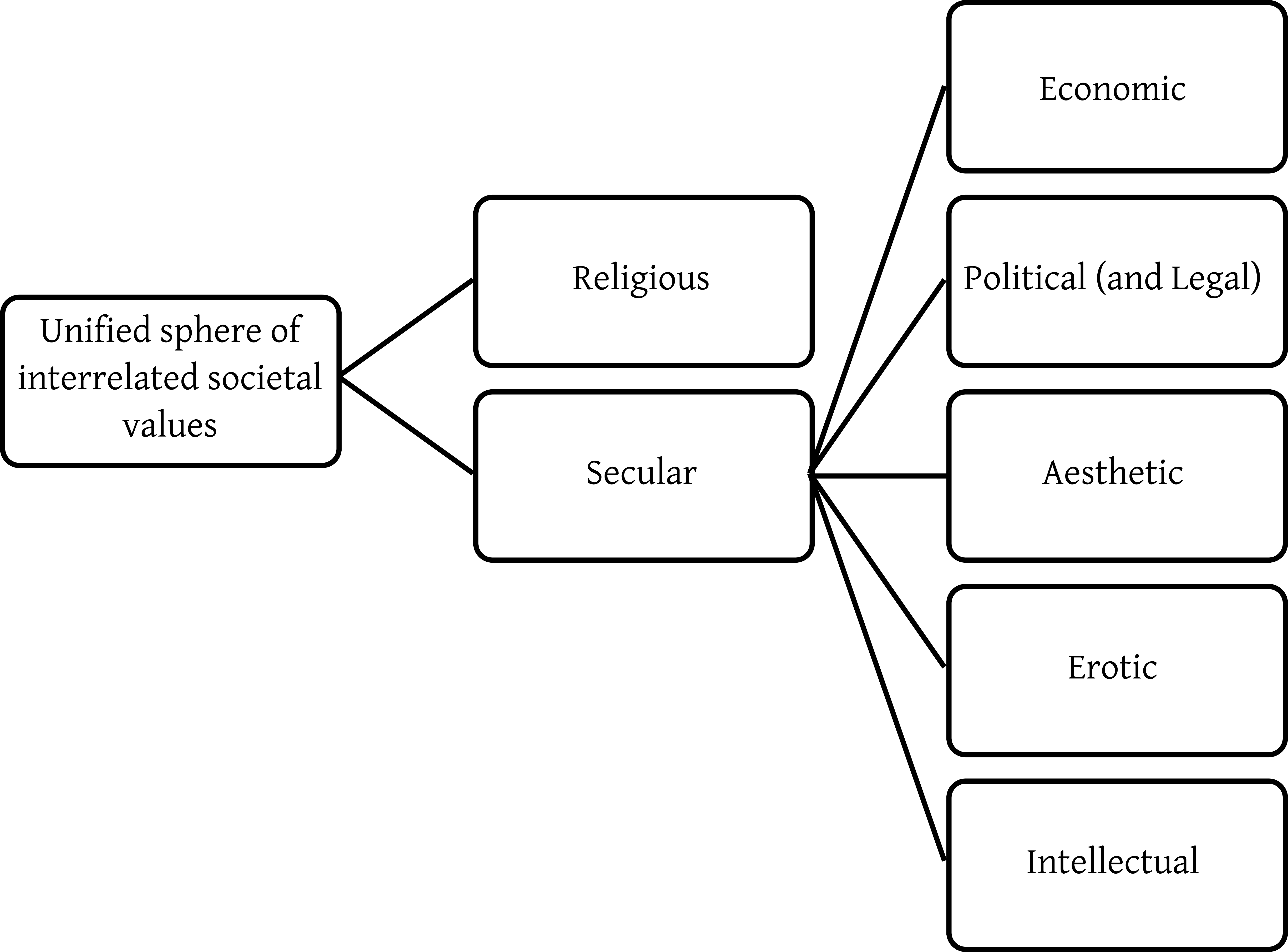

Figure 1: Table outlining the Weberian sublimation of Wertsphären.

In his theory of the rationalization and sublimation of Wertsphären, or value spheres, the German sociologist and scholar of religion Max Weber ([1920]

1986a) argues that in societies featuring a religion similar to what Jan Assmann called

primary religion—that is, a type of religion grounded in ritual and primarily transmitted

orally (J. Assmann 2006, 122–26; see also Nygaard and Schjødt; Schjødt 2013)—the

divide between the religious and the secular did not exist. Such societies feature

a more or less “unified” sphere of interrelated societal values (see Fig. 1). According

to Weber, it is not

until the coming of the so-called “sublimierte Erlösungsreligion” [sublimated religion(s)

of salvation] (Weber [1920] 1986a, 542)—Assmann’s secondary religions, which are text-based and

textually canonized (J. Assmann 2006, 122-26; cf. A. Assmann 2008)—that this divide

appears. In this paradigm, as societies slowly develop, tensions

arise within the value spheres and they are differentiated into economic, political

(including legal), aesthetic, erotic, and intellectual value spheres. Consequently,

before this state of “Rationalisierung und bewußte Sublimierung der Beziehungen des

Menschen zu den verschiedenen

Sphären” [rationalization and conscious sublimation of people’s relationship to the

various

spheres (of value)] (Weber [1920] 1986a, 540) it is hard to distinguish between religious

and secular segments of society and their

affiliated roles. Since the pre-Christian Nordic religion of Viking Age Iceland in

all likelihood was a primary religion (Nygaard 2018; ; Nygaard and Schjødt 2018;

Schjødt 2013; see also Steinsland 31–34), the society in which it existed might be

thought to have been governed by the same

lack of differentiation between religious and secular roles. This notion may be exemplified

by the many connections between law and religion in the sources for the pre-Christian

North. As is the case with all Old Norse sources about pre-Christian Iceland (and the rest

of the North for that matter), the Old Norse legal codes were naturally written down

by Christian scribes well after the Christianization of Iceland. This means that the

Christian worldview will have influenced large parts of the source material at hand,

which makes working with this material as a source for pre-Christian law and ritual

a difficult task. Nonetheless, by operating with a model like the one based on the

Weberian value spheres as well as cultural memory studies, it should be possible to

suggest and (re)construct tendencies in the material that correspond to our understanding

of pre-Christian Nordic and Icelandic society (cf. Schjødt 2012, 2013).

Spatial Sacralization in Legal Contexts

A telling example of the pre-Christian Icelandic relationship between law and religion

is the connection that is often made between legal and sacral space (see also, for

instance, Murphy 2018a; Riisøy 2013; Sanmark). Sacral space may be understood as space

that is differentiated from its surroundings

by being assigned a subjective value (of being sacral) by those who use the space

for their religious and ritual practices (Murphy 2016, 144). It is differentiated

by the “religious beliefs and cultural constructions operative within the society

which originally

engendered the spaces” (Murphy 2016, 145). Examples of terms for such places from

the Old Norse textual corpus, which are also

used below, are helgistaðr and vé (both “sacral place”). An instance of this ritualization and sacralization of legal

space may be seen

in Grágás itself, where the lǫgsǫgumaðr is described as having the role of granting people

seats at Lǫgberg:

EN lög sogo maðr a at scipa lögberg oc utlagaz þeir iii. morcom er at olofe hans sitia þar. Nu bioða menn þav oscil logsogo manne. at láta hann eigi ná seto sini. eþa þa menn er hann hefir ein nefnda til þess at sitia at lögbergi með ser oc varðar þat fiorbaugs garð oc scal þat sekia sem aðra þings afglöpon (Grágás 216)

Not only is it the role of the lawspeaker to give out the places in a seemingly ritualized (or at least formalized) manner, but he should also fine or prosecute people who misbehave or hinder him in performing his duties. They break the sacrality of Lǫgberg by ignoring the subjective value assigned to the space.[The Lawspeaker has the right to give people places at Lögberg, and people who sit there without his leave are fined three marks. If men behave so improperly towards the Lawspeaker that they do not let him get to his seat, or those men he has individually named to sit at Lögberg with him, the penalty is lesser outlawry and it is to be prosecuted like other kinds of assembly balking (SN: lit. obstruction)] (Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 1980, 193)

This sacralization of the legal space seems to be a common feature in early Scandinavian

law as exemplified by pre-Christian Icelandic and Scandinavian material. Both Old Norwegian provincial laws and narratives about legal space in the Íslendingasǫgur

mention this phenomenon. Eyrbyggja saga ch. 4 recounts how Þórolfr mostrarskegg established his þing-site (heraðsþing) on the point of the headland where he came ashore, which he named Þórsnes due to

Þórr’s apparent role in deciding the location. It is related how the place was “svá

mikill helgistaðr, at hann vildi með engu móti láta saurliga vǫllin” [such a sacred

place that he [Þórólfr] would not let the ground be defiled in any way] (Eygbyggja saga 10). Again, it is paramount that the sacrality of the legal space should not be broken.

The description of Þórólfr’s landnám (land-taking, settlement) in Landnámabók ch. S85, however, relates that following a conflict during a þing-meeting, blood

is spilt on the site making the place óheilagr [unholy, desacralized]. Accordingly, the complex has to be moved further inland because

its subjective value

has been ignored and defiled. Another famous saga-narrative features a similar sacralization

of legal space and following prohibition of violence, that is, of breaking the spatial

sacrality. Egils saga ch. 56 (154–57) relates how Egill Skalla-Grímsson visits the Gulaþing in Western

Norway and sees

the presumed tenth-century practice of erecting vébǫnd (vé-ropes)—a practice also described in the twelfth-century Frostuþingslǫg for Trøndelagen (127; see also Frense 157–76. cf. von See 129–30). The concept vé,

as noted above, is an Old Norse term for a sacral place (see Murphy 2016, 2018a;

also attested in eddic poems like Grímnismál st. 13 and Lokasenna st. 51). In Egils saga, the judges are described as seated inside the vébǫnd and, furthermore, a prohibition

of carrying weapons inside the vébǫnd was in place, presumably to prevent the breaking

of the sacrality. The erection of vébǫnd may also have been practised at the Icelandic

Alþingi if we are to judge from an expression found in Grágás (Murphy 2018a, 36). Here, the absent judges are said to be “um vés úti” [outside

the vé] (Grágás 1974, 76)—at the very least it seems to describe the subjective value of the legal space in

distinctly religious terms. Further connections between legal and ritual space may

be found on the Forsa rune ring from Hälsingland, Sweden (Hs 7, Samnordisk runtextdatabas), the so-called earliest law in Scandinavia (Brink 1996; Bugge). This early Viking

Age inscription concerns the restoration of a vi (ON vé) site

and the fines relating to the failure to do so. This restoration could refer to a

responsibility of periodical maintenance (see Ruthström) or alternatively to a punishment

for breaking the sacrality of the vi-site. In summation,

transgression is forbidden within the sacralized legal space and this, together with

the use of the term vé/vi, or sacral place, in connection with such sites seems to

firmly connect the spheres of law and religion in the pre-Christian North.

The Preoccupation with Religion in Úlfljótslǫg

The connection between law and religion is further emphasized in the contents of the

fragmentary Úlfljótslǫg, best preserved in the Hauksbók version of Landnámabók ch. 268 (see also Aðalsteinsson 34–36, 158–77). These fragments are the only remaining pieces of the presumed earliest Icelandic

law brought back to Iceland from Western Norway by Úlfljótr. He learnt it there from

his maternal uncle Þorleifr hinn spaki. According to Íslendingabók ch. 2, the law that Úlfljótslǫg is based on was an early version of Gulaþingslǫg, the law of Western Norway in the Viking Age. Furthermore, it is believed that Gulaþingslǫg stems from as early as the ninth century (Strauch 1999, 184; 2011, 114), and, for

Úlfljótr and his uncle to be able to use it as a model, “dass das Gulathingsrecht

in Norwegen damals bereits fest eingeführt war” [that the Gulaþingslǫg already was firmly established in Norway at this time] (Strauch 2011, 114).

The preoccupation shown with the religious sphere in the fragments of Úlfljótslǫg in the Old Norse text is crucial. This fact has also been noted by Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson

(158–77), who re-established the fragments handed down to us as examples of genuine

pre-Christian

legal material with a “close relationship … between the law and religion” (Aðalsteinsson

177). In fact, the description of Úlfljótslǫg’s contents is initiated by referring to it as “hinna heiðinu laga” [this pagan law]

(Landnámabók 313). Three main fragments can be identified.

Firstly, there is the article concerning figure heads on ships and the prohibition

against sailing “at landi með gapandi hǫfðunum eða gínandi trjónim, svá at landvættir

fælisk við” [towards the land with gaping heads or yawning snouts, so as to not frighten

the landvættir] (Landnámabók 313). The landvættir, or spirits of the landscape, mentioned here are a rather opaque,

anonymous collective of Otherworldly beings connected to the local landscape (as their

name would imply; see also Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar ch. 33), and their role in the pre-Christian North is not well established. However, they

seem to be connected to the West-Norse area specifically, and do not appear to have

a mythological role, as they are not mentioned in the mythological eddic poems or

in Snorri’s Gylfaginning or Skáldskaparmál (de Vries 1956–57, I: 260–61; Dillmann 327–28). Some limited evidence exists concerning

the practice of food offerings to the landvættir

according to the fourteenth-century Heimslýsing ok helgifræði found in Hauksbók (1892-96, 167). Here the practice of consecrating food to the

landvættir, then eating the food in

order to gain prosperity, is described. If these fragmentary sources are followed, the landvættir thus seem to have a part

in the lived, local religion of a specific area. Furthermore, Jon Hnefill Aðalsteinsson argues that this first article of Úlfljótslǫg could well have originated in the Settlement Era and could have served as a means

to secure a good relationship not merely between the settlers themselves but also

with the Otherworldly beings of the local landscape (163).

Secondly, Úlfljótslǫg features the description of an oath-ring—an arm ring of precious metal to be worn

during sacral activities, such as oath swearing and sacrifice—, which should be placed

on a stalli (stone plinth or altar) in the pagan sacral building known as the hof. It is described as follows:

Baugr tvíeyringr eða meiri skyldi liggja í hverju hǫfuðhofi á stalla; þann baug skyldi hverr goði hafa á hendi sér til lǫgþinga allra, þeira er hann skyldi sjálfr heyja, ok rjóða hann þar áðr í roðru nautsblóðs þess, er hann blótaði þar sjálfr. (Landnámabók 313)

Here, the connection between ritual and law is clearly evident. The oath-ring has its place in the sacral space of the hof-building, whether this was a separate cultic building or a sacralized hall. According to Eyrbyggja saga ch. 4, the goði (who is a prime example of a specialist in both law and religion, as will be treated below) furthermore had to wear the oath-ring on his arm at all gatherings, presumably because it was a significant part of his ritual garb (Sundqvist 2007, 27). Before being used as part of a sacral legal assembly, the goði has to sacralize it further through reddening it with the blood of an ox presumably sacrificed at the þing-site itself. Aðalsteinsson argues that the ritual use of the blood-reddened ring in the oath-taking ceremony was significant because it was meant to draw the attention of the gods to the legally binding ritual, which would strengthen the contractual binding of those involved for fear of “the wrath of the gods” (Aðalsteinsson 165; cf. Habbe 140). This indeed highlights the need for religiously supported sacralization in connection with pre-Christian law.[A ring of two-ounce weight or more should lie in each main hof on the stalli; this ring the goði should have on his arm at all general assemblies, which he himself had charge of, and he himself should redden it beforehand with the red blood of an ox, which he himself had sacrificed there. ]

The second article of Úlfljótslǫg then goes on to highlight the oathtaking before performing legal business at the

assembly. The oath is of a special character, which is very much connected to the

religious sphere:

Hverr sá maðr, er þar þurfti lǫgskil af hendi at leysa at dómi, skyldi áðr eið vinna at þeim baugi ok nefna sér vátta tvá eða fleiri. “Nefni ek í þat vætti,” skyldi hann segja, “at ek vinn eið at bauga, lögeið; hjálpi mér svá Freyr ok Njǫrðr ok hinn almáttki áss…” (Landnámabók 1968, 313)

Some scholars have been critical towards the source value of this passage (see, for instance, Olsen 34–49; von See 125–28). However, as discussed by, for instance, Aage Kabell, Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson and more recently Anne Irene Riisøy (2016), the swearing on rings seems to be a genuinely pre-Christian legal practice (also noted by Olsen 48). This is most likely also the case for the invoking of the names of Old Nordic gods (Riisøy 2016). The identity of hinn almáttki áss has, however, been much discussed and may indeed be a case in point for the possible Christian influence on our sources noted above. Is it the Christian God, Óðinn, Þórr, or another Old Norse god more commonly connected with oaths, such as Ullr (cf. Atlakviða st. 31) or Týr (cf. Lokasenna st. 38 and Aðalsteinsson 36, 170–74)? Olaf Olsen identifies hinn almáttki áss with the Christian God, translating the text as the “Almighty God”, thus dismissing the source value of this passage altogether. Olsen (48–49) argues that the formula must be an altogether Christian invention, mainly due to the lack of the idea of divine omnipotence in pre-Christian North. This is a very reasonable objection. Furthermore, the trio of gods, Olsen argues, invokes the idea of the Holy Trinity, since the Old Norse gods seldom appear in trios, the most prominent exception being the trio of gods at Gamla Uppsala in Adam of Bremen’s account (ch. 26). Ritually invoking gods in trios is, however, seen in Hákonar saga góða ch. 13, where toasts are said to be drunk to “Óðinn … en síðan Njarðar full ok Freys full” (Óðinn … and thereafter Njǫrðr’s toast and Freyr’s toast) (Hákonar saga góða 168), suggesting that this trio of gods might have been the one hinted at in Úlfljótslǫg. If hinn almáttki áss was originally a pre-Christian god, Óðinn is thus a candidate (see also, for instance, Turville-Petre 1972, 18). Even if the all-powerful god should be a later Christian addition or substitution for an older, unknown god, the oath swearing involving rings does seem to be genuinely pre-Christian (Riisøy 2016, 147–48). Whoever the last god of the oath may be, the spheres of religion and law seem again to be intertwined in this the earliest instance of Icelandic law.[Every man who needed to perform any legal business at the court should first swear an oath on that ring and name two or more witnesses. “I mention this,” he should say, “that I swear an oath on the ring, a lawful oath, so help me Freyr, Njǫrðr, and the all-powerful god…” ]

Thirdly, Úlfljótslǫg describes the division of the land into four quarters as well as the placement of

hófuðhof (main hof) in each quarter. Each hof has its goði who is supposed to both take care

of the cultic building as well as pass judgements and lead the course of justice at

the þing-assemblies. The source value of this particular section of the law has not

been viewed as on par with the preceding two parts of Úlfljótslǫg, and in all likelihood it is not a product of the tenth century (Aðalsteinsson 177;

see also Olsen 42–45). However, in it, its author(s) have preserved the idea of the

ideal role—or perhaps

memory—of the Icelandic goði as also noted above (see further in, for instance, J.

V. Sigurðsson 1999). This is corroborated by other descriptions of goðar (plural of goði), for instance, Þorólfr in Eyrbyggja saga ch. 3-4 (see also Sundqvist 2007, 24–28). Furthermore, according to the third article

of Úlfljótslǫg in Landnámabók ch. H268 and to Eyrbyggja saga ch. 4, the goði also had the responsibility of collecting hoftollr, a payment to the keeper of the hof. In short, we are dealing with a figure with political, legal, religious, and economic

roles.

As has been shown above, the spheres of what we call law and religion could not be

readily separated in the pre-Christian North based on the brief overview of selected

sources . This also means that the people who dealt with law often also had a role

to play in what could be deemed religious matters. In Úlfljótslǫg, the connections are so strong that it is hard to tell where the religious sphere

ends and the legal begins—or vice versa (see also Aðalsteinsson 177). Following Weber,

this may be explained by the fact that in the pre-Christian North

the distinction was not as clear cut if it indeed was applicable at all. In the case

of the early Icelandic goði, the Weberian value spheres seem truly inseparable. The

lǫgsǫgumenn were chosen from the lǫgrétta, which consisted of 48 goðar and their advisors

(Grágás K117; J. V. Sigurðsson 2001). It would thus seem plausible to argue that as the lǫgsǫgumenn

were also goðar by

definition, the role of the early lǫgsǫgumenn may also have been both legal and religious

because of this double role—not purely secular as has been argued by, for instance,

G. Sigurðsson (2004, 2018).

The lǫgsǫgumenn were also the persons who were responsible for the transmission of

the oral law in pre-Christian Iceland. This process, as noted above, could be designated

as a cultivation of cultural memory, in which the connection between religion and

law seems to be further strengthened.

The Transmission of Oral Law as a Cultivation of Cultural Memory

As noted above, it can be argued that the earliest Icelandic fragments of law, known

as Úlfljótslǫg, are based on legal material from southwestern Norway stemming from as early as the

ninth century (Strauch 1999, 184; 2011, 114). This, in turn, may have rested on an

earlier oral, legal tradition. However, keeping

to the idea of a connection to ninth-century Norwegian oral law means that by the

early tenth century the oral laws of pre-conversion Iceland, brought there from Norway,

could be considered to be cultural memory as envisioned by Aleida and Jan Assmann

(for instance, A. Assmann 1999, 2011; J. Assmann 1988, 2006, 2008, 2011). To be clear,

cultural memory is the form of collective memory that outlasts the

three-generation time span of communicative memory (c. 80-100 years); requires institutionalization and specialized, trained carriers;

and is transmitted in mediated form by these specialists (J. Assmann 2008). It should

come as no surprise that the Icelandic lǫgsǫgumenn would be seen as such

memory specialists (for instance, G. Sigurðsson 2018). These memory specialists were

able to remember and recall large amounts of information

and as such they may be some of the people mentioned in Íslendingabók ch. 1 and 9: the type of person “es langt munði fram” [who could remember a long

way back] (4) or “es bæði vas minnigr ok ólyginn” [who had both a reliable memory

and was truthful] (21; see also Hermann 2020). From a legal perspective such “treasurers

of cultural memory” (Brink 2014, 198), as Stefan Brink has termed them, may also be

found in the Swedish minnunga mæn (Brink 2014). This description as cultural memory bearers arguably also applies

to the lǫgsǫgumenn.

As noted above, the early lǫgsǫgumaðr has traditionally been seen as a secular figure

juxtaposing him with the later lawspeakers who were often connected to the church.

Gísli Sigurðsson (2004), for instance, has argued that the focal point of the power

of the lǫgsǫgumenn shifted

from the secular to the religious in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—that is,

from their oral abilities and training to an association with the medieval Church

and law-books. However, as I have aimed to show above, this distinction between the

religious and the secular does not seem to be appropriate in the general legal and

cultural context of pre-conversion Iceland. Looking at the descriptions concerning

two specific early lǫgsǫgumenn seems to further corroborate this notion. That is,

in addition to their function as memory specialists, which has been noted above, they

also seem to have religious, ritual responsibilities. These many roles may stem from

the fact that the lǫgsǫgumenn were also goðar as noted briefly above. The multifunctionality

of the goði and thus also of the lǫgsǫgumaðr with its blend of religious, ritual,

legal, and political competencies is the focus of the following sections, which investigate

the two last lǫgsǫgumenn of the tenth century, according to Íslendingabók ch. 5: Þorkell máni, lǫgsǫgumaðr from 970-84, and Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagóði, lǫgsǫgumaðr from 985-1001

(G. Sigurðsson 2004, 66–67). What follows is an analysis of the descriptions of these

two individuals and their

doings found mainly in Íslendingabók and Landnámabók. The description of Þorkell máni given in Landnámabók is as follows:

Sonr Þorsteins var Þorkell máni lǫgsǫgumaðr, er einn heiðinna manna hefir bezt verit siðaðr, at því er menn vitu dœmi til. Hann lét sik bera í sólargeisla í banasótt sinni ok fal sik á hendi þeim guði, er sólina hafði skapat; hafði hann ok lifat svá hreinliga sem þeir kristnir menn, er bezt eru siðaðir. (Landnámabók 1968, 46)

In this description, as it is transmitted both in the Sturlubók and Hauksbók versions of Landnamabók as well as in Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, two things are highlighted: the fact that Þorkell had been a lǫgsǫgumaðr and his religion. The style of Landnámabók in general betrays a preoccupation with the “details of common life” (Pálsson and Edwards 12), and religion does not seem to be the primary concern of the author(s) of this genealogical account. However, the lǫgsǫgumaðr Þorkell máni is described as a pagan. He was the noblest of pagans, and he led as pure a life as the best of Christians—ultimately, converting on his deathbed. Why include these two specific elements connected to law and religion in this description? The answer may lie in the fact that these two concepts were intrinsically intertwined in the Settlement Era. This is even clearer in the chief narrative about the most famous early lǫgsǫgumaðr, Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagóði.[Þorsteinn’s son was Þorkell máni, the lǫgsǫgumaðr, who was one of the best heathen men who ever lived as far as anyone can tell. He let himself be carried into the sunlight when fatally ill, and handed himself over to the God who had created the sun; he had lived as pure a life as the best of Christian men. ]

The conversion of Iceland in 999/1000 and the Christianization efforts of the preceding

years described in Íslendingabók ch. 7 are probably known to most readers. Following a somewhat failed attempt to convert

the Icelandic population by the missionary Þangbrandr, King Óláfr Tryggvason receives

promises of help with the Christianization from the Christianized chieftains Gizurr

hinn hvíti, Hjalti Skeggjason, and Hallr á Síðu. Ultimately, after some conflict at

the Alþingi, the Christian Icelanders ask Hallr á Siðu to recite the Christian law,

but he agrees with the pagan lǫgsǫgumaðr Þorgeirr that Þorgeirr should speak it. Þorgeirr

then famously goes “under the cloak” (cf. Aðalsteinsson), retreating from the outside

world for an entire day and night. What happened under

that cloak has been discussed at length—a discussion that is summarized very thoroughly

by Aðalsteinsson. When Þorgeirr ultimately announces his recommendation to the Alþingi, it is difficult

to argue that he acts as a ritual and memory specialist. His announcement does take

place from the presumably sacralized space of Lǫgberg, but it does not necessarily

constitute an instance of the cultivation of cultural memory through ritual, periodical

transmission (see below). However, Þorgeirr was also a goði with ritual and religious

capacities, as noted above, and in preparation for making his announcement he may

have used his knowledge of and connection to the Other World when under the cloak

(see also, for instance, de Vries 1958; Frog 2019, 279–81; Aðalsteinsson 103–04).

Aðalsteinsson contends that Þorgeirr’s speech has long been given too much attention

in the research on the conversion narrative, and that instead the ritual of going

under the cloak must be paid more heed. Following a comparison with other saga sources

as well as sources concerning Lapp, Northern Norwegian, and Irish traditions, Aðalsteinsson

concludes “that Þorgeir did not stay under the cloak to think but to carry out an

ancient soothsaying

ritual” (123). He thus connects Þorgeirr’s actions with the composition of poetry,

divination,

the practice of seiðr, as well as shamanism. What all these quite different phenomena have in common is

a connection to the numinous and the Other World. Jan de Vries (1958) holds that

Þorgeirr lay on the ground under his cloak in order to communicate with

the vættir, also mentioned above, and that “[w]enn ein solcher Mann sich in dieser feierlichen

Weise auf den Boden legt, so wussten

Sie, dass es eine frétt war” [when such a man lays down on the ground in such a solemn manner, then they

[the people

attending the þing] knew that is was a frétt] (82). That is, people knew that he was

asking the gods or Otherworldly beings for advice

on what to do in this very difficult situation. Frog (2019, 281) mentions Þorgeirr’s

covering himself as a part of a common theme of covering oneself

while going into trance in shamanistic rituals across Northern Europe. Frog thus categorizes

this ritual as shamanistic and at the same time not connected to Finns or Sámi peoples

as shamanistic practices often are in the Old Norse texts. In her response to Frog’s

article, Margaret Clunies Ross rightly notes that the contention that Þorgeirr’s ritual

actions should be seen as shamanistic has not been readily accepted in the scholarship

(301). Ultimately, both Aðalsteinsson, Frog, and de Vries argue in differing ways

that

Þorgeirr thus seeks and gets numinous advice in this ritual involving the cloak and

further that this was known by those present at the Alþingi.

According to Kristni saga ch. 12, Hallr á Siðu pays Þorgeirr Ljósvetningsgóði money to recite both the pagan

and the Christian laws. This is also related in Njáls saga (271) and Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar in mesta (1958-2000: II, 191), although the amount differs in the three accounts (see also

Grønlie 25, fn. 71). The underlying assumption seems to be that Þorgeirr was bribed

in order to make

his decision in favour of the Christians (Ólsen 1900: 86; Jóhannesson 1974, 134–5;

this interpretation has, however, been contested ). Whatever Þorgeirr’s motives might have been, from a ritual studies perspective

it is not crucial whether or not he received payment. What matters in a ritual is

not motivation, but whether or not the ritual is properly performed by a ritual specialist

(Rappaport 114). Þorgeirr performed the ritual underneath the cloak, and being a goði

we can assume

that he did so following the appropriate ritual conventions: this is what matters,

not his personal motives.

After reaching his decision using and relying on his ritual and religious knowledge

and skill and perhaps following advice from the Other World, Þorgeirr calls together

people at Lǫgberg where he gives his speech voicing his concern that a civil war will

break out if the Icelanders cannot have the same law. He refers to how Norway and

Denmark have enjoyed peace ever since both countries converted to Christianity. Then

Þorgeirr says:

“En nú þykkir mér þat ráð,” kvað hann, “at vér látim ok eigi þá ráða, es mest vilja í gegn gangask, ok miðlum svá mál á milli þeira, at hvárirtveggju hafi nakkvat síns máls, ok hǫfum allir ein lǫg ok einn sið. Þat mun verða satt, er vér slítum í sundr lǫgin, at vér monum slíta ok friðinn.” … Þá vas þat mælt í lǫgum … en of barnaútburð skyldu standa in fornu lǫg ok of hrossakjötsát. Skyldu menn blóta a laun. (Íslendingabók 17)

The key part here is the phrase ok hǫfum allir ein lǫg ok einn sið. This emphasizes the notion that the law (lǫg) and religion (siðr, lit. tradition) are intertwined and hard to separate. In fact, they seem to depend on each other. A change in religion means a new law built on this new religion. Presumably, this means that the old law (forn lǫg) was built on the old, pre-Christian religion. This is indicated by the fact that important aspects of the pre-Christian Nordic religion such as the eating of horse flesh are kept in the new law as well as by the compromise stipulating that pagans were allowed to sacrifice in secret, presumably among themselves and indoors (de Vries 1958, 82). Additionally, if the old law in any way resembled the fragments of Úlfljótslǫg discussed above, this contention seems to be supported further. As shown above, Úlfljótslǫg as it has come down to us in Landnámabók ch. H268 is so preoccupied with religion and ritual that it is difficult to separate the spheres of law and religion in the preserved text. This seems to indicate that while law and religion were naturally not exactly the same thing, they were so interrelated in pre-Christian Icelandic culture that both spheres must have been a part of the role of the early lǫgsǫgumenn. Part of this complex field was in all likelihood also the transmission of early oral law. In the following, it will be argued that viewing this transmission process as a ritualized cultivation of cultural memory may give an idea of how the transmission might have taken place, thus further expanding on the probable ritual role of the lǫgsǫgumaðr.[“And it now seems advisable to me,” he said, “that we too do not let those who most wish to oppose each other prevail, and let us arbitrate between them, so that each side has its own way in something, and let us all have the same law and the same religion. It will prove true that if we tear apart the law, we will also tear apart the peace.” … It was then proclaimed in the laws that all people should be Christian … but the old laws should stand as regards the exposure of children and the eating of horse-flesh. People had the right to sacrifice in secret.] (Grønlie 9)

Oral Transmission of Law as a Ritualized Cultivation of Cultural Memory

That the transmission of law in pre-conversion, pre-literate Iceland, as well as the

rest of the North, was oral can hardly be questioned (Foote 1977a, 1977b; Kjartansson;

McGlynn; Strauch 2011, 3). What can, however, be questioned is the form this transmission

took. In the medieval

Icelandic law code Grágás we find a description of the process of periodical recital of the entire Icelandic

law by the lǫgsǫgumaðr, conducted over the course of three summers at the Alþingi

meetings. This process has generally been thought to more or less reflect the process

of oral transmission of law in Iceland in the Viking and early Middle Ages (Dennis,

Foote, and Perkins 1980, 12–13). However, in his 2009 article “Law Recital According

to Old Icelandic Law,” Helgi Skúli Kjartansson doubts the relevance of what he calls

the “reiterative law recital” (100) as a tool for transmission of law by lǫgsǫgumenn

in a pre-literate Viking Age, Icelandic

context. Such periodic recital of the entire law sees no parallels in other Germanic

legal traditions and may have been a short-lived, eleventh-century Icelandic practice

providing an alternative to codified law. Kjartansson writes:

He thus favours the private, one-on-one tutoring of the master-apprentice relationship as the staple of pre-literate lǫgsǫgumaðr training and education in Iceland, presumably akin to the scenario described in the well-known chapter 57 of Færeyinga saga. Here, a nine-year-old apprentice is instructed in legal tradition by an older legal expert. When asked what the boy had learned from his master, Þrándr, “hann kvezk numit hafa allar saksóknir at sœkja ok réttarfar sitt ok annarra; lá honum þat greitt fyrir” [he said that he had learnt all about prosecuting lawsuits and his own legal rights and those of others; he [Þrándr] had made it available to him] (Færeyinga saga 115). This form of training was no doubt integral to the process of oral transmission of law, but it may only convey part of the story. In the terms of Jan and Aleida Assmann, the cultivation of legal material in the Viking Age and early Middle Ages would constitute a part of cultural memory cultivation (J. Assmann 1988, 2008). Cultural memory, as noted above, firstly implies institutionalization, meaning that it “requires institutions of preservation” (J. Assmann 2008, 111) in order to survive. Otherwise, the material would be forgotten. Secondly, cultural memory requires specialized carriers of memory or memory specialists who form the group that make up the institution of preservation (J. Assmann 2008, 114; see also Brink 2014; G. Sigurðsson 2018). Here, the master-apprentice relationship that Kjartansson favours is key, since it constitutes a way in which the cultural memory can be passed on between individuals and where a memory specialist can be formally trained. Thirdly, cultural memory is social and collective and needs to be communicated to the group in order to exist. As Pernille Hermann has put it, “due to its social and communicative components, cultural memory is not thought to be something that is inside individuals; rather, it exists between individuals” (Hermann 2009, 288). That is, for pre-literate law to exist and be useful outside the master-apprentice relationship it must be communicated publicly to the wider group. Naturally, the lǫgrétta is a collective, they were the institution of preservation, but the people of the Alþingi were not all part of this group. They also needed a way to access their legal cultural memory in order to act according to it. The question then remains how this might have been done.Rather, it may have been an isolated Icelandic experiment, commencing perhaps either shortly before or after the codification effort of 1117-1118, both initiatives reflecting the same motivation to modernise and standardise the country’s law (100)

Jan Assmann’s ideas of transmission of cultural memory in oral cultures highlight

the need in such cultures for ritualized, collective transmission (J. Assmann 2006,

39–40, 2008; 114–18; Nygaard and Schjødt). It may be argued that the periodical performance

of legal material by a memory specialist

such as the lǫgsǫgumaðr as described in the medieval Icelandic sources would be an

entirely appropriate mode of public, collective communication in a pre-literate, Viking

Age Icelandic society.

Kjartansson’s contention that the periodical, reiterative recital of law described

in Grágás should not be seen as a relevant form of transmission of law in the pre-Christian,

pre-literate Viking Age context could thus be reassessed—on theoretical grounds at

least—if the cultivation of law in Viking Age Iceland is viewed as a ritualized cultivation

of cultural memory. Working with this theoretical memory studies model would seem

to grant us the possibility for this reassessment. Furthermore, it would fit well

with the relationship between law and religion described above. The periodical, reiterative

recital of law would then be the official, public, collective reconstruction of (legal)

cultural memory where the old traditions are refreshed in the minds of the Alþingi

attendants and where new laws were also introduced.

at segia up lǫg: The Role of the Lǫgsǫgumaðr

In the section of the Grágás called lǫgsǫgumannsþáttr [The Law Speaker’s Section], the role of the lǫgsǫgumaðr is described: he had to

recite the þingskǫp (Assembly Procedure) each summer; give advice in interpretations of the law; allocate

seats at Lǫgberg; and announce the decisions of the lǫgrétta. The primary responsibility,

however, seems to have been to recite the law, at segia up lǫg, a third every summer so that he got through it in its entirety at least once during

his three-year term. What this entirety may have been in pre-conversion Iceland, is

of course difficult to tell. As scholarship on orality has long since established,

oral cultures and their traditions are based on a different notion of both stability

and fluidity and feature different models of, for instance, verbatim recollection

(Foley 1991, 2002). For example, a “word” was not necessarily the same in an oral,

Icelandic context as it is to us modern

consumers of written text, but, following John Miles Foley, could more productively

be seen as meaningful units of utterance ranging from formulae to stock scenes (Foley

2002; see also Frog 2014, 2016). This means that while the oral law was no doubt structured

around stable central

concepts and themes, considerable room for adaptation and variation-within-limits

in all likelihood existed in the individual performances by the lǫgsǫgumenn. Nonetheless,

the relevant part of lǫgsǫgumannsþáttr reads:

Sva er en mælt at sa maðr scal vera nockor auallt a lanðe óro er scyldr se til þess at segia log monnom. oc heitir sa lögsogo maðr … Þat er oc mælt at lögsögo maðr er scylldr til þess at segia up lög þátto alla þrimr sumrom hueriom. en þingscop huert sumar … Þat er oc at logsogo maðr scal sva gerla þátto alla up segia at engi vite eina miclogi ger. (Grágás 1974, 208–09)

This means that we are dealing with a person, who—at least in pre-literate Iceland—had to recite the law from memory, that is, perform it (Rigney 217; cf. Schechner). This is, moreover, done in the presence of the institution of memory specialists from which the lǫgsǫgumaðr is chosen (Grágás K116–117; see J. V. Sigurðsson 2001): the collective of the lǫgrétta [Law Council] along with the rest of the attendants at the Alþingi. This generally corresponds with the structure of transmission of cultural memory in oral societies proposed by Jan Assmann (for instance, 2006, 39). This tripartite structure must include processes of 1) preservation; 2) retrieval; and 3) communication, which for Assmann entails poetic form as a mnemonic tool; ritual performance in the form of a complex context consisting of, among other things “voice, body, mime, gesture … and ritual action” (J. Assmann 2006, 39); and collective participation achieved through coming together and being personally present at collective assemblies (J. Assmann 2006, 39–41). In the case of the periodical recital of law in pre-conversion Iceland, it seems that the communication through collective participation at an assembly is almost obvious, since this was the whole point of the upp segia of the lǫgsǫgumaðr at Lǫgberg. The remaining two functions may not seem readily apparent in the material and will thus be discussed further.[It is also prescribed that there shall always be some man in our country who is required to tell men the law, and he is called the Lawspeaker … It is also prescribed that a Lawspeaker is required to recite all the sections of the law over three summers and the assembly procedure every summer … It is also prescribed that the Lawspeaker shall recite all the sections so extensively that no one knows them much more extensively.] (Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 1980, 187–88)

Concerning the first function, preservation, the legal material in pre-Conversion Iceland seems to have been preserved through

a preoccupation with formalization. This is highlighted by the work of scholars of

early Nordic law on the orality of this legal tradition, who point to it having relied

to some extent on formalized, formulaic language (for instance, Brink 2005, 2011).

Such formalization and memorization for the sake of stability, it can be argued,

is at the core of Assmann’s considerations of the function of preservation (J. Assmann 2008, 114–15). While Jan Assmann favours poetic form

as the main form of preservation of cultural

memory in oral cultures, such processes are naturally culturally specific to the oral

tradition in which it originates. Furthermore, oral poetic form may be many things

and does not necessarily take the form of Western poetry that many have come to expect

(see Foley 2002). This means that we might be hard-pressed to find recognizable poetic

form at the

heart of the preservation of early law in pre-conversion Iceland—something else may

be at stake. This is also indicated by earlier research into, for instance, the poetic

and alliterative quality of early Icelandic law. Peter Foote (1987) has argued that

the laws were memorized by the lǫgsǫgumenn in spite of the apparent

lack of poetic qualities. Foote notes that memorization in Viking Age Iceland was

very different to modern-day parallels and would have been much more akin to practices

by medieval monks. He writes:

These areas highlighted by Foote are precisely where we find some of the admittedly very sporadic evidence of formulaic language in Grágás. Following the work of Michael P. McGlynn, examples of this memorization process for the naming of witnesses may be found at work in the form of formulaic expression and phrases in the section of Grágás called Þingskapaþáttr (Assembly Procedures Section, K20-85). One pertinent example is the formulae nefna þena þegn. This “ritual utterance” (McGlynn 531) was supposed to be said by a chieftain when he nominated a judge: “ec nefni þena þegn i dóm. oc nefna hin a nafn” [I nominate this good man and true to join the court — and name him by name] (Grágás 39; Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 1980, 54). According to McGlynn, the use of þegn in the first pair of alliterating words as a metonymic word referring to a good and true citizen rather than to a thane specifically points toward this word-pair being an oral formula preserving an archaic style (531–32). The second pair of alliterating words oc nefna hin a nafn, may then be a specific legal formula used to prevent the usage of nicknames or other imprecise ways of referring to the candidates.The matter was indeed chewed and digested, pondered and assimilated. What would remain longest and widest in verbal memory would doubtless be the procedural forms which any householder might require, publishing a suit, naming witnesses, summoning neighbours, challenging panels, delivering a dependent, betrothing a daughter, and so on. (Foote 1987, 56)

A second alliterative formulaic expression, which was seemingly known across Scandinavia

(Foote 1987), is arinn ok eldr [hearth and fire]. It can be found in the section called réttr leiglenðings in Landabrigðisþáttr of Grágás (K219), as well as in both the Norwegian Frostuþingslǫg, and Swedish Östgötalagen (Foote 1987, 55), where it is thought to appear with the same symbolic meaning

(Ehrhardt 179, 180)—although, as Foote notes, the contexts of the three cases are

not the same (Foote 1987, 55). The context in Landabrigðisþáttr is the prohibition of subletting land with the penalty of lesser outlawry for both

the original tenant and the subletter who “arne ok ellde fór a land hans at oleyfe

hans” [moved hearth and fire onto the owners land without his leave] (Grágás 136; Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 2000, 150). This means that we are again firmly in

the domain suggested by Foote as most likely

to remain in verbal memory and perhaps also to contain formulaic, poetic language:

that is, the realm of “procedural forms which any householder might require, [e.g.

for] publishing a suit” (Foote 1987, 56). Thus, while this may seem to be very little evidence indeed of poetic, formulaic

language of possible oral law having been carried over into the thirteenth century

recording of Grágás, it does seem to indicate that this may have been a part of the oral transmission

process.

The second function of Assmann’s structure, the retrieval through ritual performance,

can be seen in the descriptions of the recital found in lǫgsǫgumannsþáttr: an act that is heavily ritualized. Taking a point of departure in Roy A. Rappaport’s

definition of ritual acts, as “the performance of more or less invariant sequences

of formal acts and utterances

not entirely encoded by the performers” (Rappaport 24), this description of ritual

acts may also be said to encompass the recital of law

by the lǫgsǫgumaðr. Firstly, the time and space of the recital—or performance—is set

off from normal everyday life (Rappaport 37–46); it has been sacralized, as argued

above. The invariance of the recital is stipulated

in lǫgsǫgumannsþáttr, which notes that the legal knowledge of the lǫgsǫgumaðr should be so extensive “that

no one knows them much more extensively” (Dennis, Foote, and Perkins 1980, 188).

The legal oral formulae, as noted above, as well as the stipulation that the recital

is to take place every year at the same time (Grágás K116) and include the entire law (see, however, above; Grágás K19) would secure the formalization of the recital by the lǫgsǫgumaðr by building

on “conformity to form, repetitiveness, regularity, and stylization” (Rappaport 46).

The contents are likewise something fit for such ritual performance. Keeping in

mind the characteristics of cultural memory noted above, the legal material cultivated

orally over more than a century belongs to a tradition entrusted to a select few,

initiated, specialized carriers who were the bearers of cultural memory (cf. Brink

2014, 198)—the contents of the law are not encoded entirely by the performing lǫgsǫgumaðr.

All in all, the act of periodical recital of law by the lǫgsǫgumaðr can be argued

to have been a ritualized cultivation of cultural memory, and as such it is entirely

appropriate as a form of transmission of collective legal tradition in an oral society.

Concluding Remarks

The contents of the early legal material treated in this article show such an intricate

connection with religious knowledge and ritual action that the role of religion can

be said to have been crucial in the process of transmission of oral, legal knowledge

in pre-Christian Iceland. This points towards the fact that the Weberian value spheres

of the religious and the secular were very much intertwined in pre-conversion Iceland.

Together with the fact that the lǫgsǫgumaðr was also a goði with inherently ritual

responsibilities and religious knowledge (as also seen in Íslendingabók ch. 7’s description of Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagóði), this furthermore points towards

the role of the pre-Christian lǫgsǫgumenn being

both religious and secular specialists, not purely secular, as has hitherto been argued.

This suggests that through their role as memory specialists they were able to not

only draw on legal knowledge but also on religious information and ritual skills in

their transmission of early law as a cultivation of cultural memory.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper presented at the 17th International Saga Conference

in Reykjavík/Reykholt in July 2018—900 years after the purported codification of Hafliðaskrá. I am grateful to the participants in the session for their feedback. I thank my

fellow editor Yoav Tirosh for many constructive comments and suggestions throughout

the writing process, Luke John Murphy for feedback on both language and content, as

well as the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and constructive suggestions.

Any and all shortcomings and errors remain my own.

NOTES

- On the two main manuscripts for Grágás (Staðarholtsbók and Konungsbók) see Dennis, Foote, and Perkins (1980, 15). Konungsbók is thought to be the older and is more comprehensive. Vilhjálmur Finsen’s edition (1974) is quoted throughout this article.

- As this article was in the proofreading stage, I was made aware of two studies that explicitly treat the connection between law and religion in the pre-Christian North by Klaus von See and Bo Frense respectively. These studies represent two very different views on the relationship between law and religion and thus also result in two very different conclusions. For instance, Frenseʼs study sees the connection between law and religion as essential to pre-Christian Nordic culture and his conclusion “att rättssyn och rättspraxis gavs sakral anknytning” [that legal views and practices were given a sacral connection] (Frense 264) and his focus on legal rites as a crucial way of giving actions legal validity in the pre-Christian North would in various ways support the argument of this article. Von Seeʼs more critical approach would be good to engage with on matters of controversy although his conclusion that the scant evidence of a religious origin of Germanic legal thought “nicht als Zeugnisse eines religiös fundierten Rechtsdenkens gelten können” [cannot be regarded as evidence of a religiously founded legal thought] does not align with the conclusions of the present article. I have, however, not been able to integrate these two studies systematically into the article, but will refer to selected passages when relevant. I thank Olof Sundqvist for making me aware of these studies.

- However, Old Norse or Viking Studies in general is a very interdisciplinary research field and often scholars employ diverse approaches to the sources (cf. Murphy forthcoming). Nevertheless, traditionally, legal history and history of religion have been quite separate fields. See, however, Frense and von See.

- An English translation can be found in Weber (1986b). Weber’s idea of value rationalization has been criticized by Guy Oakes.

- All translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

- See also Brink (2020, 2003) on connections between law and religion in the Viking Age as attested in the placename record, i.e. the Swedish þing-sites of Lytisberg, probably referring to an early Viking Age ritual specialist, lytir (see also Elmevik 1990, 2003; Liberman; Sundqvist 2007) and Enhelga [holy island] probably earlier called Gudhø [island dedicated to the gods] (Calissendorff). See also Frense.

- This spatialization has been surveyed by Luke John Murphy who gathers all instances of sources involving the prohibition of violence at sacral or cultic sites, often termed vé (Murphy 2018a, 36–37). This phenomenon is often connected to legal space. It may even have been modelled upon pre-Christian Nordic cosmology as argued by Anne Irene Riisøy (2013).

- This phrase is seemingly not mentioned by von See in his treatment of the vébǫnd (129-30).

- Aðalsteinsson (160–61) has summarized the long and complex research history on Úlfljótslǫg with prominent contributions by scholars such as Konrad Maurer, Björn M. Ólsen (1885, 1889), Jón Jóhannesson (1956, 1974), Olaf Olsen, Jakob Benediktsson, and Dag Strömbäck.

- Cf. Raudvere (237) who seemingly conflates the groups of the álfar and the landvættir due to both groups being connected to the landscape in certain cases (see further in the following footnote and Gunnell 2020). This shared feature may, however, simply be because both groups have a role in local religion (see also Murphy 2018b on this topic) and thus to local areas where the landscape was of primary concern. See also, for instance, Egils saga ch. 57 as well as Nyere Gulaþings-Christenret (308) on the landvættir.

- Terry Gunnell (2020), however, suggests that this notion of sacrifice to the landvættir signifies a later blending of roles and identities between the álfar and the landvættir. This is because the álfar were described in earlier sources as the recipients of sacrifice in, for instance, the álfablót from the tenth-century skaldic poem Austrfararvísur by Sighvatr Þórðarson.

- Cf. Turville-Petre (1963) connects the landdísasteinar of the early 1800s in the Ísafjarðarsýsla in the Westfjords to the notion of the landdísir as venerated ancestors living in the local landscape. He furthermore compares them with the landvættir among others.

- Olaf Olsen (83–86) was notoriously critical of the idea of pre-Christian Nordic cultic buildings, instead favouring the use of “helligdomme i naturen” [shrines in nature] (Olsen 83). The textual sources and their low historical value are at the centre of Olsen’s arguments. However, and putting the very source-critical approach by Olsen aside (cf. Schjødt 2012; Raudvere and Schjødt 2012 on more positive approaches to the sources), since Olsen’s time of writing many new archaeological excavations of buildings that are interpreted as having a cultic significance have seen the light of day. Notable among these are the finds of so-called cultic buildings at Tissø, Sjælland, Denmark (Jørgensen 2002, 2009) and Uppåkra, Skåne, Sweden (Larsson 2004, 2006, 2007). Thus, the view on the existence of cultic building in pre-Christian Nordic religion has been nuanced somewhat (see, for instance, Kaliff and Mattes; Sundqvist 2016).

- This is also noted by von See (107-08).

- See also Aðalsteinsson (165–67) on the slight textual variation between two versions of this article found in Hauksbók and Þorsteins þáttr uxafóts.

- See further in Sundqvist (2017) on the significance of blood and bloody sacrifice in pre-Christian Nordic religion.

- Peter Habbe (140) argues that this connection—he uses the term interdiscursivity—between religion and law displayed in Úlfljótslǫg is not a general trait in the Íslendingasǫgur “utan at det gäller enbart när det judiciella motivet handlar om sanningsfrågor” [but it applies only when the legal motive concerns questions of truth] (Habbe 140).

- Later scholars have been less categorical (for instance, Riisøy 2013, 2016; Brink 2002; Sundqvist 2002, 327; 2007, 175–76). Von See (126-27) shares Olsenʼs opinion and argues for Christian influence on the oath and the figure of the almáttki áss.

- Declan Taggart has, however, recently conducted a study suggesting the presence of the ideas of divine monitoring and superperception in the sources about the Nordic gods: that is, the ability of gods to observe the actions of humans without being close to them.

- Several other trios of deities also spring to mind. For example, Óðinn, Hœnir, and Loðurr in Vǫluspá st. 17-18; Óðinn, Vili, and Vé in Gylfaginning (2005, 11) (although they seem to be a variant of the trio in Vǫluspá); Óðinn, Hœnir, and Loki in Skáldskaparmál (1998, 1–2); and the three named vanir-gods Freyja, Freyr, and Njǫrðr.

- Klaus Düwel has been very critical towards all aspects of Snorri’s description of the rituals and Hlaðir in Hákonar saga góða and rejects the pre-Christian relevance of the toasts to the gods. Düwel, in turn, has been criticized by scholars such as Anders Hultgård and Olof Sundqvist (for instance, 2016). See also Lönnroth for a memory perspective on toasts.

- Óðinn is not the only candidate. Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson (36, 170–74), for instance, identifies the all-powerful god with Týr, based on a comparison with Ancient Greek god Zeus, who also was invoked during oath-taking, while Jens Peter Schjødt (2020b) argues the case of Þórr due to his apparent popularity in Iceland at the time (see Gunnell 2015; Turville-Petre 1972, 4–6).

- It has been debated whether the notion of hoftollr is at all pagan or, in fact, modelled on the Christian tithe-system. Olsen (43–47) deems it overtly Christian, while Sundqvist (2016, 195–97) is more nuanced in his treatment.

- The life of Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagóði is described in several other sources, all of which have been surveyed by Aðalsteinsson (99–102). I keep to the narrative of Íslendingabók, since it contains the most information regarding his role as a lǫgsǫgumaðr. The efforts to strip Þorgeirr of his goðorð in Ljósvetninga saga are also interesting, but are omitted for lack of space.

- The version of events described in Kristni saga ch. 12 does not differ substantially from the one found in Íslendingabók ch. 7. Perhaps, Jan de Vries (1958) contends, Kristni saga relies on Íslendingabók along with other sources now lost to us for its conversion account (78–79). Kristni saga contains more detail when, for instance, relating the fact that both parties—pagans and Christians—wish to better their odds by sacrificing two people from each Quarter.

- Curiously, Aðalsteinsson does not reference Jan de Vries’ 1958 article at this point in his book. De Vries, it must be noted, was one of a group of influential scholars of the twentieth century who was sympathetic towards and active in the Nazi Party. De Vries was stripped of his academic position and spent three years in internment after the Second World War for collaboration and for being active in the SS-Ahnenerbe (cultural heritage) think tank (see Kylstra). In general, much research still used in study of pre-Christian Nordic religion today was conducted in the 1920-40s in a highly problematic relationship with the Nazi Party. See Franks (44–51) for an insightful and critical survey of the problemtic heritage of scholars such as Lily Weiser and, in particular, Otto Höfler. See Zernack for a treatment of the role of Old Norse mythology in politics, ideology, and propaganda in general.

- De Vries (1958) rejects the involvement of money and, when discussing the somewhat ambiguous phrase in Íslendingabók ch. 7 “hann [Hallr] keypti at Þorgeiri,” de Vries claims that “[w]ie sonst oft, bedeutet kaupa hier nur ‘etwas mit einem vereinbaren’; dabei braucht eine Geldsumme weder gegeben noch empfangen zu sein.” [As often elsewhere, here kaupa simply means ‘agree on something with someone’; a sum of money need not have been given nor received] (80). He goes on to claim that this neutral meaning of the term kaupa at was distorted negatively by later Christian scribes and gives the presumably earliest account in Íslendingabók precedence. Aðalsteinsson is of the opinion that a bribe would have been in vain, since the lawspeaker was only one of many goðar in the lǫgrétta to be convinced (98).

- See Nordberg for an up-to-date and very nuanced treatment of the term siðr as used in our sources.

- While both Frense (168–72) and von See (107–09) treat the figure of the goði at some length, neither connect the lǫgsǫgumaðr to the sphere of religion and ritual (although they mention the title once each: Frense 169; von See 107).

- Forgetting is, however, inherently important to the concept of cultural memory. See, for instance, Connerton.

- See also Carruthers (1998, [1992] 2008) for an elaboration on the role of memory and remembering in composition of oral traditions and in the training of memory.

- On the contested meaning of the term þegn see Sukhino-Khomenko.

- Another possible indication of the use of poetic language in memorization is the section Baugatal in Grágás: the scale of wergild payment, which, according to Lúðvik Ingvarsson, does not make much sense in early medieval Icelandic society, if the scale was simply transposed to contemporary standards (see also Foote 1987, 63). Nevertheless, it is part of the medieval law, and possibly this is due its archaic language, which contains many words with only poetic parallels (Foote 1987, 55). Ingvarsson has, on these grounds (among others), argued for its relevance in pre-Christian Iceland and proposed its roots to be in the Viking Age society.

- This understanding of invariance would naturally have followed the oral, culturally specific notions of such processes in pre-conversion Iceland.

REFERENCES

- Aðalsteinsson, Jón Hnefill. 1999. Under the Cloak: A Pagan Ritual Turning Point in the Conversion of Iceland (Kristnitakan á Íslandi). Translated by Jón Hannesson and Terry Gunnell. Reykjavik: Háskólaútgáfan; Félagsvísindastofnun.

- Adam of Bremen. 1917. Hamburgische Kirchengeschichte. Edited by Bernhard Schmeidler. Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Separatim Editi. Magistri Adam Bremensis Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Hanover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung.

- Assmann, Aleida. 1999. Erinnerungsräume: Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses. Munich: Beck.

- ⸻. 2008. “Canon and Archive.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook. Edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 97–107. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ⸻. 2011. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Assmann, Jan. 1988. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65: 125–33.

- ⸻. 2006. Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ⸻. 2008. “Communicative and Cultural Memory.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook. Edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 106–18. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ⸻. 2011. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Atlakviða. In Eddukvæði, 2: Hetjukvæði. Edited by Jónas Kristjánsson and Véstinn Ólason, 372–82. Íslenzk fornrit. Reykjavik: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Austrfararvísur. 2012. By Sigvatr Þórðarson, edited and translated by Robert Fulk. In Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages: Vol. 1: Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Edited by Diana Whaley, 578–614. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Benediktsson, Jakob. 1974. “Landnám ok upphaf allsherjaríkis.” In Saga Íslands, I. Edited by Sigurður Líndal, 155–223. Reykjavik: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag.

- Brink, Stefan. 1996. “Forsaringen: Nordens äldsta lagbud.” In Beretning fra femtende tværfaglige Vikingsymposium. Edited by Else Roesdahl and Preben Meulengracht Sørensen, 27–55. Aarhus: Forlaget Hikuin.

- ⸻. 2002. “Law and Legal Customs in Viking Age Scandinavia.” In The Scandinavians from the Vendel Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Edited by Judith Jesch, 87–110. Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology 5. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

- ⸻. 2003. “Legal Assemblies and Judicial Structure in Early Scandinavia.” In Political Assemblies in the Earlier Middle Ages. Edited by P. S. Barnwell and Marco Mostert, 61–72. Studies in the Early Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols.

- ⸻. 2005. “Verba Volent, Scripta Manent? Aspects of Early Scandinavian Oral Society.” In Literacy in Medieval and Early Modern Scandinavian Culture. Edited by Pernille Hermann, 77–135. The Viking Collection 16. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press.

- ⸻. 2008. “Law and Society: Polities and Legal Customs in Viking Scandinavia.” In The Viking World. Edited by Stefan Brink in collaboration with Neil Price, 23–31. London: Routledge.

- ⸻. 2011. “Oral Fragments in the Earliest Swedish Laws.” In Medieval Legal Process: Physical, Spoken and Written Performance in the Middle Ages. Edited by Marco Mostert and P. S. Barnwell, 147–56. Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 22. Turnhout: Brepols.

- ⸻. 2014. “Minnunga mæn – The Usage of Old Knowledgeable Men in Legal Cases.” In Minni and Muninn: Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture. Edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, and Agnes Arnórsdóttir, 197–210. Acta Scandinavica 4. Turnhout: Brepols.

- ⸻. 2015. “Early Law in the North.” Questio Insularis 16: 1–15.

- ⸻. 2020. “Law and Assemblies.” In Pre–Christian Religions of the North: History and Structures. Edited by Jens Peter Schjødt John Lindow, and Anders Andrén, 445–77. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Bugge, Sophus. 1877. Rune–Indskriften paa ringen i Forsa kirke i Nordre Helsingland, udgivet og tolket af Sophus Bugge. Saerskilt aftryk af Christiania Universitets festskrift i anledning af Upsala Universitets jubilaeum i september 1877. Oslo: H. J. Jensens bogtrykkeri.

- Calissendorff, Karin. 1964. “Helgö.” Namn och bygd 52: 105–52.

- Carruthers, Mary J. 1998. The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ⸻. (1990) 2008. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Clunies Ross, Margaret. 2019. “Response.” Response to “Understanding Embodiment Through Lived Religion: A Look at Vernacular Physiologies in an Old Norse Milieu,” by Frog. In Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia. Edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson, 297–301. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.

- Connerton, Paul. 2008. “Seven Types of Forgetting.” Memory Studies 1 (1): 59–71.

- Dennis, Andrew, Peter Foote, and Richard Perkins. 1980. Laws of Early Iceland: Grágás, the Codex Regius of Grágás, With Material from Other Manuscripts, I. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- ⸻. 2000. Laws of Early Iceland: Grágás, the Codex Regius of Grágás, With Material from Other Manuscripts, II. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- Dillmann, François–Xavier. 2007. “Vættir.” In Vol. 35 of Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, 326–34. 2nd ed. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Düwel, Klaus. 1985. Das Opferfest von Lade: Quellenkritische Untersuchungen zur germanischen Religionsgeschichte. Wiener Arbeiten zur germanischen Altertumskunde und Philologie 27. Vienna: Karl M. Halosar.

- Egils saga. 1933. Edited by Sigurður Nordal. Íslenzk fornrit 2. Reykjavik: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Ehrhardt, Harald. 1977. Der Stabreim in altnordischen Rechtstexte. Heidelberg: Winther.

- Elmevik, Lennart. 1990. “Aschw. Lytis– in Ortsnamen: Ein kultisches Element oder ein profanes?” In Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place-Names. Edited by Tore Ahlbäck, 490–507. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 13. Åbo: Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History.

- ⸻. 2003. “En svensk ortnamnsgrupp och en hednisk prästtitel.” In Ortnamnssällskapets i Uppsala (2003), 68–78.

- Eyrbyggja saga. 1935. Edited by Einar Ól. Sveinsson and Matthías Þórðarson. Íslenzk fornrit 4. Reykjavik: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

- Foley, John Miles. 1991. Immanent Art: From Structure to Meaning in Traditional Oral Epic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ⸻. 2002. How to Read an Oral Poem. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Foote, Peter. 1977a. “Oral and Literary Tradition in Early Scandinavian Law: Aspects of a Problem.” In Oral Tradition Literary Tradition: A Symposium. Edited by Hans Bekker-Nielsen, Peter Foote, Andreas Haarder, and Hans Frede Nielsen, 47–55. Odense: Odense University Press.

- ⸻. 1977b. “Some Lines in Lǫgréttuþáttr.” In Sjötíu ritgerðir helgarðar Jakobi Benediktssyni 20 júlí 1997. Edited by Einar G. Pétursson and Jónas Kristjánsson, 198–207. Reykjavik: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar.

- ⸻. 1987. “Reflection on Landabrigðisþáttr and Rekaþáttr in Grágás.” In Tradition og historieskrivning: Kilderne til Norden ældste historie. Edited by Kirsten Hastrup and Preben Meulangracht Sørensen, 53–64. Acta Jutlandica 63 (2). Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Franks, Amy Jefford. 2019. “Valfǫðr, vǫlur, and valkyrjur: Óðinn as a Queer Deity Mediating the Warrior Halls of Viking Age Scandinavia.” Scandia: Journal of Medieval Norse Studies 2: 28–65.

- Frense, Bo. 1982. Religion och rätt: En studie till belysning av relationen religion–rätt i førkristen nordisk kultur. Lund: Department of Theology.