SCANDINAVIAN-CANADIAN STUDIES/ÉTUDES SCANDINAVES AU

CANADA

Vol. 25 (2018) pp.92-114.

Title: “Writing Beyond the Ending” and Diasporic Narrativity in Loveleen Rihel Brennaʼs Min annerledeshet, min styrke

Author: Marit Ann Barkve

Statement of responsibility:

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Marked up by

Martin Holmes

Statement of responsibility:

Guest Editor/Rédactrice invitée

Marit Ann Barkve University of Wisconsin–Madison

Guest Editor/Rédactrice invitée

Marit Ann Barkve University of Wisconsin–Madison

Statement of responsibility:

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Journal Editor/Rédactrice du journal

Helga Thorson University of Victoria

Statement of responsibility:

Technical Editor

Martin Holmes University of Victoria

Technical Editor

Martin Holmes University of Victoria

Marked up to be included in the Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal

Source(s):

Barkve, Marit Ann. 2018.

“Writing Beyond the Ending” and Diasporic Narrativity in Loveleen Rihel Brennaʼs Min annerledeshet, min styrke.Scandinavian-Canadian Studies Journal / Études scandinaves au Canada 25: 92-114.

Text classification:

Keywords:

article

article

Keywords:

- immigration

- feminism

- multiculturalism

- diaspora

- literature

- MDH: started markup 25th August 2017

- MDH: encoded intro 28th August 2017

- MDH: finished encoding 29th August 2017

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 5th September 2017

- MDH: entered general editor's proofing corrections 22nd January 2018

- MDH: added abstract translation. 14th February 2018

- MDH: entered editor's proofing corrections 26th October 2018

- MDH: finalization and page-numbers hard-coded 30th October 2018

- MDH: proofing corrections arising from print copy 5th November 2018

“Writing Beyond the Ending” and Diasporic Narrativity in Loveleen Rihel Brennaʼs Min annerledeshet, min styrke

Marit Ann Barkve

ABSTRACT: This article analyzes Loveleen Rihel Brenna’s memoir, Min annerledeshet, min styrke (2012) [My Otherness, My Strength]. It focuses on Brenna’s use of literary appropriation techniques, the memoirist’s

use of intertextuality, and the role of the Bildungsroman genre in her memoir. The article begins by contextualizing Brenna’s diasporic location.

Then, using concepts inspired from Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s book Writing Beyond the Ending (1985) in conjunction with intertextual references from Brenna’s memoir, the article

offers

a close reading of Min annerledeshet, min styrke to explore the complexity of Brenna’s use of the conventional and unconventional

patterns of the female Bildungsroman genre in order to understand how her use of the genre engages with the question of

women and multiculturalism in Norway.

RÉSUMÉ : Cet article analyse les mémoires de Loveleen Rihel Brenna, Min annerledeshet, min styrke (2012) [Mon altérité, ma force]. Il met l’accent sur l’utilisation par Brenna des techniques d’appropriation littéraire,

l’utilisation de l’intertextualité par l’autobiographe et le rôle du genre Bildungsroman dans ses mémoires. L’article commence par contextualiser la situation diasporique

de Brenna. Puis, en utilisant des concepts inspirés du livre de Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Writing Beyond the Ending (1985) (en français, Écrire au-delà du dénouement) et des références intertextuelles tirées des mémoires de Brenna, l’article offre

une lecture attentive de Min Annerledeshet, min styrke, afin d’explorer la complexité de l’utilisation, par Brenna, de modèles conventionnels

et non conventionnels du genre féminin Bildungsroman, afin de comprendre comment son utilisation du genre aborde la question des femmes

et du multiculturalisme en Norvège.

Introduction

“Is multiculturalism bad for women?” Susan Moller Okin posed this question in a 1999

Boston Review article and sparked a debate that polarized feminist scholarship. In this article

Okin sowed the seeds for a debate over multiculturalism versus feminism that continues

to be relevant in Norway today. Okin argued that group rights may problematically

override the purportedly universal rights of women, as some cultural groups are more

patriarchal than others. Although Norway has been globally renowned as a champion

for gender equality, the country has also experienced the relatively recent immigration

of people from non-Western cultures whose gender values appear to clash with Norwegian

values. The debate is further complicated as it challenges the national discourse

of tolerance. This combination of factors has ignited a vigorous discussion about

the crisis of Norwegian gender equality in the media, in academia, among Norwegian

feminists, and among Norwegians of immigrant background.

Two images exemplify this ideological clash, or Norway’s struggle to reconcile Norwegian

feminism with multiculturalism. The first is Shabana Rehman’s self-portrait published

in Dagbladets Magasinet, a popular Norwegian weekly (Ringheim). In the controversial image (see Figure 1),

Rehman throws aside a teal garment to reveal her nude body painted in the Norwegian

flag’s brilliant blue, red, and white. The image depicts Rehman’s transition from

an oppressed immigrant Muslim to an empowered Norwegian woman. Rehman is intentionally

provocative in her message. In reference to this image she told Time magazine that she “is a free woman” and that she “take[s] [her] clothes off to provoke

the authorities in order to expose them” (Wallace). She uses her status as a celebrity

to provoke and to prod the “authorities” (the Pakistani patriarchy and the Norwegian

media) to inquire as to why the women’s

question takes second priority to ethnic preservation in Norway’s Pakistani community.

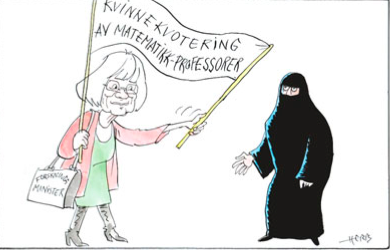

The second image was published in Avisa Nordland [Nordland’s newspaper] on March 8, 2008 (see Figure 2) in honour of International

Women’s Day and was also

published and discussed in the book Likestilte norskheter: Om kjønn og etnisitet (2010) [Equal Norwegianness: On Gender and Ethnicity]. The cartoon depicts Tora Aasland,

Norway’s Minister of Research and Higher Education,

picketing with a sign that demands: “KVINNEKVOTERING AV MATEMATIKK-PROFESSORER” [FEMALE

QUOTAS FOR MATH PROFESSORS] as a burqa-clad woman looks on (Berg, Flemmen, and Gullikstad 10-11). Additionally,

motion squiggles illustrate that Aasland is in the process of passing

one of the two supporting handles of her picket sign to the burqa-clad woman as though

inviting her to join in on the Norwegian gender equality struggle. The juxtaposition

of Norway’s stereotypical women-friendly quotas against the cultural practices of

some of the country’s new Norwegians aptly portrays Norway’s gender equality dilemma.

Figure 1

Shabana Rehman, a Pakistani-Norwegian comedian and public figure, throws off her traditional Pakistani clothing in favour of revealing her naked body painted with the Norwegian flag.

Shabana Rehman, a Pakistani-Norwegian comedian and public figure, throws off her traditional Pakistani clothing in favour of revealing her naked body painted with the Norwegian flag.

Figure 2

The cartoon depicts Tora Aasland, Norway’s Minister of Research and Higher Education, picketing with a sign that demands “FEMALE QUOTAS FOR MATH PROFESSORS” as a burqa-clad woman looks on (“Typisk kvinn folk”).

The cartoon depicts Tora Aasland, Norway’s Minister of Research and Higher Education, picketing with a sign that demands “FEMALE QUOTAS FOR MATH PROFESSORS” as a burqa-clad woman looks on (“Typisk kvinn folk”).

These images illustrate the concept of intersectionality–in this case the intersection of gender equality, ethnicity, and religion and/or

faith–and explore Okin’s question regarding whether multiculturalism is bad for women.

Okin’s question is considered tired, even passé, in academia as it is viewed as overly

simplistic and to some scholars even racist. Yet despite its reputation in academe,

Norwegian women of immigrant background continue to investigate Okin’s question and

their intersectional citizenship by using their own life experiences as the subject

for their analysis. In this article, I analyze Loveleen Rihel Brenna’s memoir Min annerledeshet, min styrke and the way its narrator engages with the question “is multiculturalism bad for women?”

in her Norwegian-Indian context. My analysis of Loveleen’s memoir will focus on her use of literary appropriation techniques, the memoirist’s

use of intertextuality, and the role of the Bildungsroman genre in her memoir. Using concepts inspired from Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s book Writing Beyond the Ending in conjunction with intertextual references from Loveleen’s memoir, I will offer

a close reading of Min annerledeshet, min styrke to explore the complexity of Loveleen’s use of the conventional and unconventional

patterns of the female Bildungsroman genre in order to understand how her use of the genre engages with the question of

women and multiculturalism.

Loveleen Rihel Brenna: Author and Activist

At age 5, Loveleen moved with her family from India to Kristiansand, Norway (Brenna

57). Loveleen made her debut in the Norwegian media at age eighteen when she participated

in a Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) documentary that followed the lives

of multicultural youths in Norway. The documentary that introduced the Norwegian public

to the young immigrant, and vise versa, paid special attention to Loveleen’s arranged

marriage to Daljeet Kumar (Kumar 10). Loveleen has studied psychology, multicultural perspectives, pedagogy,

and has a

Masters degree from the University of Oslo in educational leadership. Loveleen’s resumé

is extensive; she has been an activist for multicultural children’s issues, a government

administrator, and an author. She has held important national positions such as: a

board member of Norway’s Red Cross, the leader of Foreldreutvalget for grunnopplæringen (FUG), the leader of the Kvinnepanelet [Women’s Panel], the leader for the Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet [Children, Equality, and Inclusion Department], and a faculty board member at Oslo

and Akershus University College (HiOA) of Applied

Sciences. In addition to her official duties, she holds courses, lectures, and seminars

about what it is like to grow up between two or three cultures (Kumar 7). These interactions

with the Norwegian public have served as inspiration for her

writing projects. She’s written several nonfiction pieces–books, articles, and blog

posts–as well as a memoir. Her first book, Mulighetens barn: Å vokse opp mellom to kulturer (1997) [Opportunity’s Child: Growing up Between Two Cultures] is a compilation of

letters she received from Norwegian children of immigrant background.

Mulighetens barn explores the reality, challenges, and identity conflicts of “bindestreksbarn” [hyphenated

children]. Most recently, Loveleen published Min annerledeshet, min styrke, which, according to Loveleen, provides an account of an immigrant woman’s successful

journey to a national leadership position (Loland). In 2012, Loveleen established

her own nonprofit, SEEMA A.S., and her own consulting firm, Loveleen’s konsulentfirma A.S., whose missions are to

assist women of immigrant background in the Norwegian job market.

Contextualization

As my literary analysis hinges on political and societal discourses, I will provide

a brief contextualization of Loveleen’s Norwegian framework. Norwegians have historically

understood and defined their country as a homogeneous nation. Norway, which gained

its independence from Sweden in 1905, was not originally known as a destination country

for immigrants but rather as a country with a population prone to emigration. In spite

of this outgoing trend, Norway was not entirely homogeneous. Coexisting alongside

the white Christian protestant majority population were the Sámi, Finns, Romany, as

well as Scandinavian nationals from neighbouring countries, among others. Even though

Norway has a long history of migration, the country’s migrant narrative tends to be

treated solely as a present-day political issue (Sturm-Martin). Due to the immigration

wave of the 1960s, Norway has experienced the growth of a

multicultural society. The country has been forced to confront new ways of conceptualizing

Norway and Norwegianness, the scholar Anniken Hagelund identifies that the phrase

“we are living in a multicultural society” has become a familiar rhetorical trope

in Norwegian politics (Hagelund 182). Grete Brochmann, a Norwegian sociologist, has

analyzed the problematic nature of

a newly multicultural society, explaining that “[n]ew multicultural states are groping

for good symbols for the new diversity. The

traditional national symbols have lost aspects of their force and legitimacy in the

conflict with both internationalization and immigration” (Brochmann 11). As the issues

of minorities and migration are unavoidable in politics and everyday

life, Norway’s political discourse and policy have begun to explore its former experiences

with cultural diversity where they previously stressed the country’s homogeneity

(Hagelund 182). Interactions between the minority and the majority population have

been far from

conflict-free. The immigration debate began as a push towards integration, with equality

as the basis for this policy, but has become a highly politicized issue. The welfare

state, created to help all within state borders, is threatened by economic exhaustion

and strained by overpopulation as well as overuse. Integration becomes an even more

challenging process when immigrant values are perceived to clash with the values of

the host country.

The Norwegian national narrative is typified, among other traits, by its commitment

to equality, particularly gender equality. Since the 1970s, due mostly to the policies

of the Labour Party, Norway has been transformed into one of the most gender equal

nations in the world. However, Anh Nga Longva, in her article “The Trouble with Difference:

Gender, Ethnicity and Social Democracy,” challenges the national narrative of equality.

Longva exposes the deceptive simplicity of the Norwegian word and concept likhet. Likhet is the Norwegian word for both equality and similarity/sameness. In Norwegian, to

be equal is synonymous with being similar, or the same. The etymology of likhet reflects the cultural understanding that to be equal is first and foremost to be

alike (Gullestad 1984, 1992, 2002; Longva). The concept of egalitarian individualism

is no stranger to the Western world, however

many researchers have argued that there is a stronger emphasis on sameness in Norway

as well as the other Nordic countries (Gullestad 2006). In her article, Longva analyzes

how Norway’s oppressed others have achieved equality

and become recognized members of Norwegian society through redistributive justice.

She begins her argument by discussing gender equality, showing that what seem to be

extremely progressive and groundbreaking proposals are problematic because they are

shaped on a male rather than a female model, where women are instead admired for “their

ability to transcend the traditional image of women as creatures for whom biology

is destiny” (Longva 158). The myth of the “strong Norwegian woman” (who is first and

foremost autonomous, a woman who can “have it all”) contributes to the pressure for

Norwegian women’s assimilation to masculine traits.

Longva’s central argument is that a mono-gendered society is not necessarily a degenderized society. The policies implemented by the Norwegian government have created a mono-gendered society with maleness as the norm (Longva 158).

Issues of equality are not just a matter of gender but also of race. In her analysis

of likhet, Longva also provides a case study of the Sámi, Norway’s indigenous population. The

Alta river protests put minority issues on the map in Norway, and, due in large part to these protests,

the Sámi have since received cultural recognition. Cultural recognition, however, was not actualized until after the Sámi in Norway

“were subjected between the 1850s and the 1960s” to harsh assimilation policies that

have “wrought extensive and, some would claim, permanent, damage on this national

minority,

such as loss of language and traditions, and a fading perception of history and identity”

(Longva 170). Longva illustrates that the Sámi people did not receive equality until

after they

had been forcibly assimilated, or Norwegianized. In regard to Norway’s relatively

new multicultural population, Longva questions likhet’s role: how is Norway to reconcile difference based on ethnicity? If ethnic minorities

follow the historical trend of Norway’s oppressed others (women and the Sámi), today’s

Norwegian immigrant minorities can hope to achieve redistributive justice only through

assimilation/Norwegianization. Is it possible, in the Norwegian context, to break

this historical trend and to think about dichotomies (male/female, indigenous/Norwegian,

Norwegian/immigrant) in a non-dichotomous way? Is it possible to distinguish between

equal and same, and unequal and different? Is an imagined sameness needed to establish

“peace and quiet”–in other words, can likhet be achieved in multicultural Norway?

Norwegian literature written by authors of immigrant background has engaged with and

complicated these questions. Within the last three decades, immigrants and their children

have contributed to rewriting the national narrative through various forms of literary

expression, for example short stories, plays, poetry, and novels (Kongslien 2006).

In their works, these new authors and performers raise questions of identity, nationality/ethnicity,

and location. This migrant expression began to emerge in other parts of Scandinavia

in the 1970s with the publication of short stories, poetry, and novels by members

of the region’s immigrant populations (Kongslien 2007, 197). However literature written

by authors of immigrant background did not appear in

Norway until 1986 when Khalid Hussain published his book Pakkis [Packi]. Ten years later, Nasim Karim published IZZAT: For ærens skyld [IZZAT: For the sake of honour], which features a female protagonist, as opposed to Hussain’s

male protagonist, and

foregrounds women’s issues. These books highlight the coming-of-age problems experienced

by second-generation immigrants of the largest immigrant group in Norway, Pakistanis

(Kongslien 2007, 209-12). These two works ushered in a new genre into the Norwegian

canon, which the literary

scholar Ingeborg Kongslien labels Norwegian “migration literature” but notes that

this literature has also been termed “intercultural literature” or “multicultural

literature” (Kongslien 2014, 113). I suggest a terminology change when discussing

this genre in a literary context

to “diaspora literature,” and I will use this term throughout this article. I suggest

this change because “multiculturalism” and “migration” are terms often associated

with failed political projects of European nation-states.

Additionally, “multiculturalism” has recently been coopted by fear-mongering right-wing

groups in Norway. Although

groups in Norway are actively attempting to reclaim the term from far-right extremists, due to the contentious political nature of the term and the baggage it carries it

isn’t a fruitful tool in a literary analysis or a discussion of literary discourse.

Although originating from the great Jewish exodus (from the Greek word diaspeirein meaning to “disperse”), diaspora in literary theory today refers to the dispersion of any people from their

original homeland. I offer Avtar Brah’s clarification of diaspora, “the concept of

diaspora offers a critique of discourses of fixed origins while taking

account of a homing desire, as distinct from a desire for a ‘homeland’” (Brah 16).

In this way, the term diaspora sidesteps nationality, while simultaneously relying

on the notion of the nation and nationhood and allowing authors to go beyond the “Norwegian

vs. immigrant” dichotomy typified by the terminology of immigrant literature, migrant

literature,

or multicultural literature. Therefore a switch to the term diaspora literature in

the field of Norwegian literary studies would better reflect the realities of modern

migration without a perceived association with far-right extremist thought.

Regardless of its label, this literature has proved integral to the Norwegian debate

over multiculturalism because it articulates the ethnic minority voice and challenges

the notion that Norway is an ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation. Memoirs

within the genre function as another vehicle for challenging Norway’s national narrative.

Memoirs written by minority women and academics have been published in Norway to mixed

reception. These memoirs, like other forms of literary expression, address issues

of identity, nationality, ethnicity, and place. Female authors of immigrant background

who write in this genre have tended to highlight their personal relationship to the

intersection of gender and Norway’s diasporic communities of which they are members.

These non-fiction memoirs are presented in various modes, for example: books, stand-up

comedy, politics, YouTube videos, journalism, and anthologies. Loveleen’s memoir offers

a unique perspective on diasporic identity that does not rely on the tired “us vs.

them” dichotomy. Her interpretation of her own life story and its Norwegian context

confronts

challenges by bridging understandings, fusing two identities together, and prioritizing

patience.

“Writing Beyond the Ending” in Min annerledeshet, min styrke

Min annerledeshet, min styrke is an attempt to “write beyond the ending.” In other words, the memoir depicts how

Loveleen broke with expected traditional gender

roles of Indian women in diaspora and gained a leadership position at a national level.

Rachel Blau DuPlessis coined the term “writing beyond the ending” in order to revise

“the way we read works written by women of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries”

(Dorr 307). She elaborates on the concept in her introduction:

In her book, which has been lauded by feminist literary critics (see Dorr), Blau DuPlessis pays close attention to narrative strategies. Blau DuPlessis argues that twentieth-century women writers used the “poetics of critique,” or rebellious narrative techniques, in order to write beyond the conventional narrative structure of the nineteenth-century romance plot. In her first chapter, “Endings and Contradictions,” she outlines the conventional pattern of the Bildungsroman with a female protagonist and identifies a convention of novelistic closure in works by nineteenth-century British women writers–most notably Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), Emma (1815), and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). The plot typically features a young girl growing into adulthood, leaving the “relational triangle” or the intense love/hate relations with her parents for an initiation into adulthood, where her destiny lies within the domestic sphere as wife/mother, her vocation and her sexuality collapsed into one (37). In the chapters that follow, Blau DuPlessis describes a variety of deviations from this conventional narrative sequence that developed because of a “desire to scrutinize the ideological character of the romance plot and related conventions in narrative, and to change fiction so that it makes alternative statements about gender and its institutions” (x). Women writers of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, via the “poetics of critique,” have challenged the conventional patterns of the female Bildungsroman by reassessing the conventional plot sequence of the novel by writing alternative and oppositional stories about men, women, and community. This breaking of the conventional pattern of the female Bildungsroman often involves the following elements:Narrative in the most general terms is a version of, or a special expression of, ideology: representations by which we construct and accept values and institutions. Any fiction expresses ideology; for example, romance plots of various kinds and the fate of female characters express attitudes at least toward family, sexuality, and gender. The attempt to call into question political and legal forms related to women and gender, characteristic of women’s emancipation in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is accompanied by this attempt by women writers to call narrative forms into question. The invention of strategies that sever the narrative from formerly conventional structures of fiction and consciousness about women is what I call “writing beyond the ending.” (Blau DuPlessis x)

- a mother/daughter relationship that is conflicted because the daughter both desires and resists the example or demands of her mother for conventional feminine destiny;

- a daughter who occasionally identifies with her father (however she is conflicted because she is not male, as he is);

- a complex and conflicting relationship between the demands of sexuality (being a wife/mother) and a desire for individualism and/or vocation; and

- a troubling adult relationship with her family, community, and nation, resulting from the rebellions against the conventional feminine destiny.

Blau DuPlessis’ observations about historical change in women writers’ narrativity

are insightful as my analysis will show how Loveleen strategically uses these two

plot sequences (both the conventional pattern and the breaking of the conventional

pattern) in her memoir in order to illustrate a move from the domestic to the public

sphere. The first half of Min annerledeshet, min styrke echoes the conventional plot sequence of nineteenth-century romance novels, whereas

the second half of the memoir breaks with the conventional plot in a manner similar

to other works of twentieth-century women writers. The conventional pattern, the first

half of the memoir, follows her coming of age under her parent’s roof, her dedication

to her husband Tito (her first husband, an Indian man Loveleen’s parents arranged

for her to marry), and her role as a mother to their two sons, Manav and Siddhant.

Loveleen describes accepting her role as an Indian wife and mother, “Jeg bestemte

meg for å bli enhver indisk svigermors drøm. Det var ikke vanskelig.

… Jeg forsvant inn i den mest indiske delen av meg for å sikre meg et godt ekteskapelig

liv som indisk hustru, svigerdatter, mor og gift datter. … Jeg lukket døren. Nordmenn

var blitt ‘de andre’” [I decided to be every Indian mother-in-law’s dream. It wasn’t

hard. … I disappeared

into the more Indian part of myself to secure a good married life as an Indian housewife,

daughter-in-law, mother, and married daughter. … I locked the door. Norwegians became

‘the other’] (Brenna 119). At this point in her life, Loveleen strove to thrive in

the conventional pattern

by being the perfect housewife, daughter, daughter-in-law, and mother. Furthermore,

Loveleen attempted to be an exemplary image of Indian femininity, which she describes

with adjectives such as “lydig, pliktoppfyllende, oppofrende, flink på skolen, flink

i husarbeid, høflig, bluferdig

og sømmelig” [obedient, dutiful, devoted, good at school, good at housework, polite,

bashful, and

modest] (Brenna 74) –adjectives that do not necessarily align with an exemplary image

of Norwegian femininity

(sporty, strong, sexy, independent, autonomous).

In stark contrast, the second half of Loveleen’s memoir rebels against the understood

conventional Indian femininity as it details her divorce, her marriage to Johnny Brenna

(a Norwegian man of her choice), and her vocational journey to a successful national

leadership role. Throughout the memoir’s turn from convention to rebellion, Loveleen

is conflicted about her Indian upbringing. She expresses anger and confusion towards

her mother (exemplifying the first point in Blau DuPlessis’ pattern), who defined

her daughters and sons by their gender roles.

Mamma sa flere ganger at hun var så stolt av oss. Vi kunne lage mat, rydde, sy, strikke, brodere, og var flinke på skolen, lydige og pliktoppfyllende. Den som giftet seg med oss, ville leve lykkelig. Det eneste hun ba om, var at Gud må gi oss familier som verdsatte oss. Av og til var det vanskelig å forstå om hun skrøt av oss, eller om dette var ros til henne selv, som hadde oppdradd oss til å bli så gode koneemner. (Brenna 88-89)

It is apparent that Loveleen loves her mother and identifies with her, but she simultaneously resists being trapped by her mother’s pride and narrow definitions of Indian womanhood. Also in line with breaking of the conventional pattern, Loveleen identifies with her father (corresponding to the second point in Blau DuPlessis’ pattern) as they both have brave, exploratory spirits. Her father established a life in a new country, and Loveleen similarly explored by creating a life beyond the domestic sphere. “For å forstå mine valg, min indre kraft og ikke minst min stahet for å nå mine mål, må jeg først fortelle om min fars reise. Hadde jeg ikke vært min fars datter, ville jeg kanskje aldri blitt hel og tro mot meg selv” [To understand my choice, my inner strength and, not least, my stubbornness about accomplishing my goal, I first need to tell about my father’s journey. Had I not been my father’s daughter, I would possibly never have been completely whole and true to myself] (Brenna 26). She takes time in her memoir to detail her father’s struggles because she identifies with his journey. Additionally, Loveleen describes her rebellion as a forced shift from her Indian identity to a Norwegian identity, much of which is attached to sexual mores in the diasporic community (see Blau DuPlessis’ third point). “Rykter og sladder ville florere uansett, så hvorfor ikke bygge seg opp til å bli et friere menneske istedenfor å la seg tynge av sladder i et undertrykkende miljø? … Den dagen jeg forlot huset for godt, fikk jeg stempelet ‘norsk’ i pannen” [Rumours and gossip will flourish no matter what, so why not build yourself up to become a freer person instead of letting yourself gravitate towards the gossip in an oppressive environment? … That day that I left the house for good, I got ‘Norwegian’ stamped on my forehead] (Brenna 152-53). In this passage she details her conflict with her family and the Indian community in her Norwegian town. Because of her decision to divorce, Loveleen experiences issues with her ex-husband when he decides to move to the United States, taking her two sons with him (Blau DuPlessis’ fourth point). Her memoir provides an example of both types of narrative sequences in one book and thus represents an effort to “write beyond the ending” in the context of an Indian diasporic community within Norway’s borders.[Mama said several times that she was proud of us. We could cook, clean, sew, knit, embroider, and were good at school, obedient, and dutiful. The one who would marry us will live happily. The only thing she prayed for was that God would give us families that appreciated us. Sometimes it was difficult to understand if she boasted of us or if it was praise for herself, who brought us up to be such good prospective wives.]

Loveleen’s own life story is an example of “writing beyond the ending,” but this strategy

is further emphasized in her memoir as she incorporates intertextual

references from the Norwegian canon (texts from nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century

authors) as sources of inspiration for her own life story. In what could be described

as overlapping intertextuality, Min annerledeshet, min styrke explores two levels of “writing beyond the ending.” Loveleen’s memoir provides accounts

of her life that are uplifting and unifying,

but she also uses intertextuality or literary appropriation to parallel her personal

narrative with narratives grounded in the Norwegian national canon. An avid reader,

she uses Norwegian literature as a way of relating to, understanding, and seeking

guidance in her own lived experiences. Works of particular significance for the first

part of her memoir and the nineteenth-century Bildungsroman plot structure include: Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter (1920–22), Camilla Collett’s Amtmannens døtre (1854–55) [The District Governor’s Daughters], Henrik Ibsen’s Et dukkehjem (1879) [A Doll’s House], and Anne Karin Elstad’s Folket på Innhaug (1976) [People of Innhaug] and Julie (1993). Loveleen uses these Norwegian works to parallel her early life with Norway’s

past:

before Norway’s Modern Breakthrough, before religious choice, before women’s liberation,

and before modernity.

Loveleen begins her memoir at her sister’s wake. Through this traumatic event, the

reader is provided an intimate and unguarded look into the Rihel family and their

community support. “Så mange blomster fra nordmenn! Dette er det sterkeste beviset

på at dere er blitt

inkludert i det norske samfunnet. Dette har jeg aldri sett i noen andre indiske hjem,

sa en av gjestene til Pappa” [So many flowers from Norwegians! This is strong proof

that you all have been included

in Norwegian society. I have never seen this, ever, in another Indian home, said one

of the guests to Papa] (Brenna 17-18). The narrator’s description of the number of

flowers sent by sympathetic Norwegians

to show their support for the Rihel family assures the reader of an eventual successful

integration experience and guarantees that the Rihel family is composed of exceptional

immigrants. The memoir then jumps back in time and details each of Loveleen’s parents’

upbringings and describes the terms of their arranged marriage. Moving linearly, the

memoir devotes chapters to Loveleen’s pre-emigrant life in India, her father’s search

for a suitable host-country (a process that necessitated sixteen separate journeys),

and her immigration to Norway together with her parents. Loveleen’s memoir reserves

significant space for commentary on her own experiences as a child immigrant in Southern

Norway, detailing cultural contrasts, gender role comparisons, the Indian community’s

cooperation and support, language and interpretation issues, Indian family values

verses Norwegian family values, religion, youth rebellion, and circular migration. Her problems reach a climax when Loveleen’s parents arrange a marriage for her with

Tito, a boy from India. In her arranged marriage, Loveleen suffers from split identity

issues; she oscillates between her husband (who views her as too Norwegian) and Norwegian

society (where she is engaged in a perpetual struggle to be “norsk nok” [Norwegian

enough]). After years of marriage and two children, Loveleen divorces her husband

(Tito’s

adultery justifies her divorce) and steps outside of the domestic sphere in order

to explore her own identity and vocation, a project she calls “Loveleen i fremtiden” [Loveleen

in the future] (Brenna 173), and which correlates to the twentieth-century Bildungsroman plot.

In chapter eleven, Loveleen’s plot sequences collide with Norwegian history and literature.

The chapter describes Loveleen’s experience at Baldewin discotheque. Loveleen lies

to her strict parents, telling them she was working a night shift at the damehjem [women’s retirement home], in order to go to a nightclub. This chapter interrogates

two concepts: the duty

of Indian daughters verses the duty of Norwegian daughters and the two narrative structures

of female protagonists (past vs. present, Indian vs. Norwegian). In chapter eleven,

Loveleen has a conversation at the damehjem with a resident, fru [Mrs.] Andersen, about another resident, frøken [Miss] Pedersen. Fru Andersen describes the plight of frøken Pedersen after Loveleen mentions that she sympathizes with frøken Pedersen who receives no visitors and never leaves the damehjem. Fru Andersen unsympathetically and harshly shares her opinion with Loveleen:

- Nei, ho kommer nok ikke i verljoset, uansett, sa fru Andersen med litt skarp stemme.

- Verljoset, hva er det?

- Nordlyset, der jomfruene går etter at de dør svarte hun. (Brenna 98)

From this conversation, Loveleen learns that frøken Pedersen gave birth to a child out of wedlock who died shortly after birth. Public knowledge of her loose morals branded her an unfit bride, thereby condemning her to living with her parents for the entirety of her adult life. Frøken Pedersen’s deviance from the conventional and accepted pattern was shameful to her family, causing them to be the subject of community gossip. Loveleen is shocked by the story and proclaims to fru Andersen, “det du forteller nå ligner veldig på den indiske kulturen” [what you’re telling me now is very similar to the Indian culture] (Brenna 99). Loveleen interprets this bit of Norwegian history as a parallel to her own present-day Indian community in Norway.[ - No, she’s probably not going to verljoset anyway, said fru Andersen harshly.

- Verljoset, what is that?

- The Northern Lights, where virgins go when they die, she answered. ]

Such conversations spark Loveleen’s interest in Norwegian literary history, particularly

books that shed light upon how Norwegian women lived in the past. She reads Ibsen’s

Et dukkehjem, Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter, and Elstad’s Folket på Innhaug. Loveleen observes that within the pages of these books “det var som å lese om meg

selv, min far, min mor, mine søsken og alle andre jeg kjente

med indisk bakgrunn. Jeg kjente meg mer igjen i disse romanene enn i indiske bøker.

Bygdedyret i bøkene var det indiske miljøet i mitt liv” [it was like reading about

myself, my father, my mother, my siblings and all of the

others I knew with Indian background. I felt more alive in these novels than in Indian

books. The characters in the books were the Indian environment in my life] (Brenna

100). Throughout the memoir, Loveleen leans on Norwegian literature as a bridge between her two lived situations,

her double identity. She notices that, “bøkene jeg leste fikk en ny dimensjon. Jeg

la mer og mer merke til likhetene mellom

den kulturen jeg var en del av og det jeg leste om, som var Norge før i tiden” [the

books that I read acquired a new dimension. I noticed with increasing frequency

the similarities between the culture I was a part of and the one I read about, which

was Norway in the past] (Brenna 131).

During Loveleen’s self-discovery process, she relies heavily upon works that encourage

a breaking away from the conventional pattern of the female Bildungsroman. For example, she describes Ibsen’s character Nora as a source of inspiration, “Ibsens

Nora ble en sterk inspirasjonskilde. Det var som om jeg så henne for meg, der

hun kjempet seg frem til en egen identitet” [Ibsen’s Nora was a strong source of inspiration.

It was like I saw her as me, the

way she fought for her own identity] (Brenna 160). Nora, Ibsen’s notorious female

protagonist, slams the door on the patriarchy in

order to explore the duties she has to herself, undertaking an implied self-actualization

project. Nora was never able to “write beyond the ending” as Et dukkehjem’s finale is literally a door closing; Loveleen however sees this as an intertextual

parallel where she can open a new door and write a new plot for herself. Other titles

Loveleen discloses as relevant to the second part of her memoir, in addition to Nora

in Ibsen’s Et dukkehjem, include David Pollock and Ruth E. Van Reken’s Third Culture Kids (1999) and Thorvald Stoltenberg’s Det handler om mennesker (2001) [It’s About People]. She also lists notable Norwegian public figures such as Arne Næss, Jonas Gahr Støre,

and Kristin Clemet. These works and inspirational figures deviate from Blau DuPlessis’s

analysis in three ways because the works are non-fiction, they aren’t all written

by women, nor are the protagonists all women. This deviation is, however, integral

to the memoir’s Norwegian context. In order to “write beyond the ending,” or to disrupt

the habits of narrative order, Loveleen clings to a Norwegian narrative of egalitarian

individualism, which Longva calls a mono-gendered individualism built upon a male model (Longva 158).

After Loveleen’s divorce and symbolic dive into a new narrative structure, her traditionalist

Indian parents cut off communication with her, as her divorce shamed the honour of

the Rihel family. Stepping out of the domestic sphere becomes a catalyst for Loveleen’s

emerging visibility and for finding her own voice. She speaks out at conferences and

begins a career writing about and counseling parents about immigrant integration in

Norway. After reconciling with her parents in a moment of crisis, they encourage her

to open up to the idea of pursuing a new husband. The memoir then jumps ahead to when

Loveleen meets Johnny Brenna, a Norwegian police officer and TV2’s crime expert; they court and eventually marry. Their courtship and marriage is complicated by multiple

issues. To name just two: Tito moves to the United States and files for custody of

his two sons, while Loveleen’s and Johnny’s demanding careers burden their relationship.

Ultimately, Loveleen retains custody of her sons who identify as more Norwegian than

Indian, her relationship with Johnny continues, and her career successfully develops into

a national leadership position with FUG and SEEMA.

Loveleen’s memoir presents a published narrative that writes beyond the typical female

immigrant experience of arranged marriage and/or violence. Marianne Skarsgård, a journalist,

highlights the uniqueness of this project, explaining that Loveleen “viser til at

det blant annet er gitt ut bøker om tvangsekteskap og vold, men ikke

noen som forteller historien om en minoritetskvinnes vei til lederjobb på nasjonalt

nivå” [notes that, among other things, books on arranged marriage and violence are

published,

but not one that tells a story about a minority woman’s path to a leadership position

at the national level] (Skarsgård). Min annerledeshet, min styrke provides an example of a minority woman’s successful journey that ends in a national

leadership position. This project is important, uplifting, and hopeful. However this

project has the potential to be quite problematic. Blau DuPlessis’ analysis of literature

requires a progressive view of history that positions these narrative structures on

a hierarchy, where twentieth-century narratives are above conventional nineteenth-century

narratives. Loveleen uses the Bildungsroman genre to situate her lived experiences within the Norwegian literary canon, which

could suggest that the Indian diasporic community in Norway lags years back on the

linear path to gender equality.

Sammensmeltning [Fusion]

Loveleen is not the first author to discuss the similarities between Norway’s Christian

past and the realities of today’s multicultural youth. Human Rights Service (HRS),

founded and led by Hege Storhaug, a prominent Norwegian feminist and anti-Muslim activist,

published a report called Feminin integrering: Utfordringer i et fleretnisk samfunn (2003) [Feminine Integration: Challenges in a Multiethnic Society] that contained

stories about the abuse and violence towards multicultural women (women

of colour) at the hands of the multicultural patriarchy (men of colour) in Norway.

The report recognizes that these narratives do not depict every immigrant family in

Norway; however HRS does find the violent narratives to encompass enough large immigrant

families to warrant concern (Storhaug and Human Rights Service 141). To translate

these oppressive narratives for a Norwegian audience, HRS used Norwegian

literary history, particularly literature of the Modern Breakthrough, to illustrate

the severity of the women’s human rights abuses.

Dette kvinneundertrykkende bildet kjenner vi igjen fra tidligere norsk (kristen) historie, der kvinner ble ansett som mannens eiendom–også i ektesengen. Våre store forfatter på slutten av forrige århundre som Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Henrik Ibsen, Gabriel Scott, Jonas Lie, Camilla Collett og Amalie Skram, har alle gjennom skjønnlitterære verker beskrevet kvinners (og menns) tragiske ekteskapelige skjebner. (Storhaug 185)

HRS draws a parallel between Norway’s literary, fictional past and the narratives they present of Norway’s current, real-life multicultural residents. The non-profit’s report likewise acknowledges the potential of “writing beyond the ending” or finding a way to break the conventional plot, as they include policy proposals that advocate for a change in Norway’s immigration laws to better “protect” women. HRS depicts immigrant communities as historical, regressive cultures and native Norwegians as having a modern, progressive culture. HRS’s report, in contrast to Loveleen’s narrative, limits itself to a narrow-minded view of “writing beyond the ending” due to its simplification of the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender. The feminist non-profit recognizes only one way of breaking the conventional plot, namely assimilating to Western, European, and Norwegian cultural and societal norms. Using Norwegian literary history in this way is highly problematic as it places the two cultural traditions in binary opposition: Norwegian/immigrant, West/East, Global North/Global South.[This image of the oppressed woman we recognize from earlier Norwegian (Christian) history, where women were considered a man’s property–also in the marriage bed. Our great authors at the turn of the last century, such as Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Henrik Ibsen, Gabriel Scott, Jonas Lie, Camilla Collett, and Amalie Skram, have all via literary works described women’s (and men’s) tragic marital fates.]

Loveleen’s narrative, however, “writes beyond the ending” in a specifically diasporic

way as she includes Indian narratives in her story. Just

as she read Norwegian literature with her first husband, she acculturates her second

husband into Indian culture.

Jeg begynte å lese bøker for ham. Litt hver dag, for det meste indisk filosofi. Deepak Chopra, Dalai Lama, Osho. Dette hadde jeg gjort før, det var nesten som om historien gjentok seg. For tretten år siden hadde jeg lest bøker av norske forfattere for Tito, de første årene etter at han kom til Norge. Nå var det en ny runde, denne gangen med Johnny. Jeg begynte å lure på om det var meg og ikke mennene det var noe galt med. (Brenna 200)

This negotiation exemplifies Loveleen’s diasporic narrativity. She negotiates between her two cultures and invites her Norwegian family to see the values and lessons of Indian culture. Loveleen finds other ways of bridging gaps and finding common ground with others who have lived dislocated or diasporic lives. She explains that “jeg likte å lese om Gandhi gjennom Arne Næss’ briller, da ble både det norske og det indiske i meg ivaretatt. Denne sammensmeltningen gjorde at jeg følte meg hel. Jeg kjente det samme i møte med norske misjonær- og diplomat-barn, som nå var blitt voksne, som hadde vokst opp i India” [I liked to read about Gandhi through Arne Næss’ lens, then both the Norwegian and the Indian in me was safeguarded. This fusion made me feel whole. I felt the same with Norwegian missionary and diplomat children, now adults, who had grown up in India] (Brenna 203). Loveleen’s sammensmeltning (fusion) calls into question essentialist models of Norwegianness as well as the idea of a homogenous Norwegian culture. She feels at home with others who understand sammensmeltningen, or those capable of a dual perspective. Sammensmeltningen is the notion of a diasporic consciousness or identity, and Loveleen invokes this fusion and duality as a positive affirmation of their identities.[I began to read books to him. A little bit every day, for the most part Indian philosophy. Deepak Chopra, Dali Lama, Osho. I’d done this before, it was almost like history was repeating itself. Thirteen years ago I had read books by Norwegian authors to Tito, the first years upon his arrival to Norway. Now it was another round, this time with Johnny. I began to wonder if it was me, and not the men, there was something wrong with.]

However as Loveleen details in this passage, “writing beyond the ending” simply isn’t

enough to live up to the liberated Western standard:

Begrepene minoritetskvinne, innvandrer, indisk jente og fremmedkulturell kvalte halve meg, følte jeg; de ugyldiggjorde og ignorerte store deler av min personlighet, mitt liv og min identitet. Det var ikke noe galt i å være minoritetskvinne, men alle de forestillingene folk hadde om minoritetskvinner, gjorde meg så annerledes fra kvinner generelt at det ble en belastning for meg. Jeg var glad i mine naboer, lærere, klassekamerater, foreldrene til vennene mine, de ansatte på butikken jeg handlet i, mine kollegaer og alle andre nordmenn jeg kjente. Jeg elsket Camilla Collett, Sigrid Undset, Henrik Ibsen, Amalie Skram, Anne Karin Elstad, Tove Nilsen og Jens Bjørneboe. Fiskeboller, fårikål, frikassé, komper, kjøttkaker og kokt torsk var blitt yndlingsrettene mine. Men selv om Norge hadde vugget meg i søvn, oppfostret meg og gitt meg omsorg og støtte i tjueåtte år, ble jeg likevel plassert i en kategori som skilte meg fra alle de andre, utenfor resten av barneflokken til “mor Norge.” (Brenna 206)

Sammensmeltning must work in two directions. Loveleen was able to “write beyond the ending” and rupture the traditional narrative structure thanks to her location in Norway, but her diasporic identity could not provide her likhet. Despite her sincere efforts, Loveleen cannot escape the Norwegian/immigrant divide.[The concepts minority woman, immigrant, Indian girl, and culturally distant suffocated me; I felt they invalidated half of me and ignored large parts of my personality, my life, and my identity. There was nothing wrong with being a minority woman, but all the stereotypes people had about minority women made me so different from women in general that it was a burden to me. I was fond of my neighbours, teachers, classmates, parents of my friends, the staff at the store I shopped at, my colleagues, and all of the other Norwegians I knew. I loved Camilla Collett, Sigrid Undset, Henrik Ibsen, Amalie Skram, Anne Karin Elstad, Tove Nilsen, and Jens Bjørneboe. Fish balls, mutton stew, fricassee, potato balls, meatballs, and boiled cod had become my favourite dishes. But even though Norway had rocked me to sleep, nurtured me, and given me care and support for twenty-eight years, I was still placed in a category that separated me from all of the others, outside the rest of “Mother Norway’s” flock of children.]

Herein lies the main goal of Min annerledeshet, min styrke: to promote sammensmeltning as a positive descriptor of Norwegian identity. In doing this, Loveleen critiques

both the Indian community in Norway and her Norwegian host country. Loveleen, who

has put down roots in Norway, asks her diasporic readers to do the same and allow

themselves to settle in their host country for the sake of their children. She also

asks her fellow Norwegian citizens to permit such a transition. To illustrate this

highly contentious and complicated process, she uses the metaphor “treet med plastposen” [tree

in a plastic bag] (Brenna 142-49). Gardening, a shared Indian and Norwegian interest,

serves as an apt metaphor for

diasporic consciousness. Loveleen compares her diasporic experience with the process

of transplanting a tree. A tree is transported from the nursery to a new garden with

a plastic bag around its roots, which parallels her Indian community in Norway, “De

hadde fått kuttet over røttene–mange av båndene til sine foreldre, søsken, naboer,

venner, landet og omgivelser. Uten å være klar over det, hadde de fått en plastpose

rundt røttene” [They had cut the roots–many of the ties to their parents, siblings,

neighbours, friends,

country, and environment. Without being aware of it, they had gotten a plastic bag

around their roots] (Brenna 145). The plastic bag is a symbol of a longing for the

homeland and one’s home traditions,

which is an approach that is often criticized for being nativist in attitude or a

form of strategic essentialism. “Jeg opplevde det indiske samfunnet i Kristiansand

som en koloni av frukttrær med plastposer rundt røttene. Selv om flere av dem hadde

bodd i Norge i tjue eller tretti år, hadde de ingen planer om å få rotfeste i ny jord”

[I experienced the Indian society in Kristiansand as a colony of fruit trees with

plastic bags around their roots. Even though many of them had lived in Norway for

twenty or thirty years, they had no plans to root in new soil] (Brenna 146). Though

they live in Norway their hearts are still in India, which impedes their ability to

thrive in Norway and complicates the lives of their children who do not have a plastic

bag around their roots. The plastic bag must be removed, but well tilled soil is also

required for a successful transplant. She notes that,

Noen av dem opplevde at det blåste kalde vinder rundt dem, og at det var tele i jorden. Holdningene og rasismen de møtte i nabolaget, på arbeidsplassen og i samfunnet generelt, gjorde det umulig for dem å ta av plastposen. Jo mer krenkelser og diskriminering de opplevde, jo vanskeligere ble det for dem å finne sin plass i samfunnet, i den nye hagen. (Brenna 146)

Balancing all of these factors, Loveleen decides to discard her own plastic bag and take root in Norway for the sake of her children’s wellbeing. However, she feels a responsibility to combat minority discrimination in Norwegian society and to use her knowledge of the migration process to assist Norwegians to cultivate soil fertile enough to accept those who dare to take off the plastic bag. She noticed “at enkeltpersoner som uttalte seg om minoritetsmiljøer, ofte manglet teorigrunnlaget og tyngden de trengte for å få gehør i fagmiljøene” [that individuals who spoke about minority communities often lacked theoretical competency and the weight needed for gaining acceptance in professional circles] (Brenna 148), so she decided that she, “måtte kombinere mine egne erfaringer med fagkunnskap” [must combine [her] own experiences with disciplinary knowledge] (Brenna 148).[Some of them felt that cold winds blew around them and that the soil was frozen. The attitudes and racism that they encountered in their neighbourhood, at work, and in society generally, made it impossible for them to take off the plastic bag. The more violations and discrimination they experienced, the more difficult it became for them to find their place in society, in the new garden.]

Loveleen sidesteps being criticized for having an assimilatory attitude because she

places the integration burden upon both native Norwegians and immigrant Indians. The

story she tells in Min annerledeshet, min styrke is one of diasporic opportunity and success. As an Indian woman in Norway, Loveleen

is able to “write beyond the ending” and self-actualize within and outside of the

domestic sphere. Though she appropriates

a notion of modernism and modern literary narratives, she is careful not to equate

modernity as synonymous with civilized, which is a profound misunderstanding found

in crevasses of Norwegian society, for example in HRS’s report. Min annerledeshet, min styrke approaches this question differently than both the images discussed above and the

conclusions drawn in HRS’s report, which place culture on a hierarchy where modern

Norway (“West”) is privileged over Eastern immigrant cultures (“the rest”). As she

said in a recent interview, “Jeg tror det er Camilla Collett som sier at du må ta

et oppgjør med dine egne fordommer

før du kan ta et oppgjør med andres” [I believe it was Camilla Collett who said that

you must confront your own prejudices

before you can deal with others’] (Uri). In Min annerledeshet, min styrke, Loveleen advocates for finding strength in difference, and she believes that learning

to view sammensmeltet (fused) identities as a positive attribute as opposed to a threat is a good task

for Norwegian schools, Norwegian families, and Norwegian society.

NOTES

- All translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

- Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989 in her analysis of women of colour in the American judiciary system. She concluded that women of colour are marginalized as “the outsider within” in a system that favours white heterosexual Christian males. Scandinavian feminist scholars have since accepted the term as both a political and analytical concept (Berg, Flemmen, and Gullikstad 14).

- I want to clarify my use of the author’s first name, Loveleen. She has published using three different last names. To avoid confusion, her first name is used in the media, and she also uses her first name in her own blog. I have therefore decided to use her first name as well.

- In the fields of literary history and literary criticism, Bildungsroman is a German term used to describe a genre of literature that describes a character’s “coming-of-age” or “formation.” Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (1795–96) [Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship] is credited as the birth of the genre. Since Goethe, the genre has been applied to a variety of lived experiences, creating sub-genres. Blau DuPlessis’s innovative text engages with the female experience as depicted in, and the breaking away from, the Bildungsroman genre.

- In her memoir, Loveleen refers to Daljeet as “Tito.”

- FUG is the Norwegian equivalent to the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) in the United States.

- SEEMA is an acronym that has a dual meaning. The company is named in Loveleen’s deceased sister’s (Sima Rihel) honour. Seema stands for Selvstendighet [Independence], Empowerment [Empowerment], Endring [Change], Mestring [Mastering], and Ambisjon [Ambition].

- The Alta river protests, also known as the Alta Controversy, was a popular movement (coordinated by Sámi/indigenous and environmentalist activists) against the development of the Alta-Kautokeino waterway on the Alta river in Finmark, Northern Norway.

- Norway acknowledged (in the 1980s) that it is a state founded on two peoples: Norwegian and Sámi; the Sámi (Sámidiggi) parliament was established in 1989; Norway is a signatory of DRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples); the Sámi language is recognized as an official language of Norway (ETS-148: European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages).

- Pakkis is a derogatory Norwegian word for people of Pakistani descent.

- Izzat is the Urdu word for “honour.”

- One example being “10 undersøkelser: Migranten” [10 Studies: Migrant] an ongoing arts-based research project funded by Office for Transnational Arts Production (TrAP).

- Greek diaspeirein “disperse” from dia “across” + speirein “scatter.” The term originates from Deuteronomy 28:25, “esē diaspora en pasais basileias tēs gēs” [thou shalt be a dispersion in all kingdoms of the earth.]

- Circular migration refers to the family’s frequent trips back and forth, from India to Norway–a practice that typifies modern migration’s flexible conception of “home.”

- Chapter 16: “Jeg tar ordet” (quotes from Anne Karin Elstad’s Julie (131-32)); Chapter 17: “Mine nærmeste fiender” (cites Henrik Ibsen, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Camilla Collett, Sigrid Undset); Chapter 19: “Utstøtt”; Chapter 24: “Gandhi og ledelse” (references David Pollock and Thorvald Stoltenberg).

- TV2 is a Norwegian commercialized television channel.

- “Mamma, jeg er glad i alle i USA, men de snakker ikke slik som du gjør. Det er andre regler der. Vi er norske. Det er ikke de” [Mommy, I love all of them in the US, but they don’t talk the way you do. There are other rules there. We are Norwegians. They are not] (Brenna 197).

REFERENCES

- Austen, Jane.1813. Pride and Prejudice. London: Printed for T. Egerton.

- ⸻. 1815. Emma. London: Murray.

- Berg, Anne-Jorunn, Anne Britt Flemmen, and Berit Gullikstad. 2010. “Innledning: Interseksjonalitet, flertydighet og metodologiske utfordringer.” In Likestilte norskheter: Om kjønn og etnisitet. Edited by Anne-Jorunn Berg, Anne Britt Flemmen, and Berit Gullikstad, 10–37. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag.

- Blau DuPlessis, Rachel. 1985. Writing Beyond the Ending: Narrative Strategies of Twentieth-Century Women Writers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Brah, Avtar. 1996. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. New York: Routledge.

- Brenna, Loveleen Rihel. 2012. Min annerledeshet, min styrke. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Brochmann, Grete. 2003. “Citizens of Multicultural States: Power and Legitimacy.” In The Multicultural Challenge. Edited by Grete Brochmann, 1–13. Oslo: Elsevier.

- Brontë, Charlotte. 1847. Jane Eyre. London: Smith, Elder, and Co.

- Collett, Camilla. 1854-55. Amtmandens Døtre. Vol. 1. and 2. Christiania: Johan Dahl.

- Dorr, Priscilla. 1985. “Reviewed works(s): Protest and Reform: The British Social Narrative by Women, 1827-1867 by Joseph Kestner; Writing Beyond the Ending: Narrative Strategies of Twentieth-Century Women Writers by Rachel Blau Du-Plessis.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 4 (2): 305–08.

- Elstad, Anne Karin. 1976. Folket på Innhaug. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- ⸻. 1993. Julie : Roman. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Gullestad, Marianne. 1984. Kitchen-table Society. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- ⸻. 1992. The Art of Social Relations: Essays on Culture, Social Action and Everyday Life in Modern Norway. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

- ⸻. 2002. Det norske sett med nye øyne: Kritisk analyse av norsk innvandringsdebatt. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- ⸻. 2006. Plausible Prejudice. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hussain, Khalid. 1986. Pakkis. Oslo: Tiden.

- Ibsen, Henrik. 1879. Et dukkehjem: Skuespill i tre akter. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Karim, Nasim. 1996. IZZAT: For ærens skyld. Oslo: Cappelens.

- Kongslien, Ingeborg. 2006. “Migrant or Multicultural Literature in the Nordic Countries.” Eurozine. Accessed 11 July 2017. http://www.eurozine.com/migrant-or-multicultural-literature-in-the-nordic-countries/.

- ⸻. 2007. “New Voices, New Themes, New Perspectives: Contemporary Scandinavian Multicultural Literature.” Scandinavian Studies 79 (2): 197–226.

- ⸻. 2014. “Migration, Translingualism, and Appropriation: New National Narratives in Nordic Literature.” In Acta Nordica, Studier i språk- og litteraturvitenskap: Globalization in Literature. Edited by Per Thomas Andersen, 111–29. Oslo: Vigmostad & Bjørke AS.

- Kumar, Loveleen. 1997. Mulighetens barn: Å vokse opp med to kulturer. Otta: J. W. Cappelens Forlag AS.

- Loland, Marianne. 2011. “Vil gjøre en forskjell.” Hegnar Online Kvinner. September 23. Accessed 16 January 2012. http://www.hegnar.no/kvinner/article682026.ece.

- Longva, Anh Nga. 2003. “The Trouble with Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, and Norwegian Social Democracy.” In Multicultural Challenge. Edited by Grete Brochmann, 153–77. Comparative Social Research, vol. 22. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Okin, Susan Moller. 1999. “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?” In Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women? Susan Moller Okin with Respondents. Edited by Joshua Cohen, Matthew Howard, and Martha C. Nussbaum, 8–24. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pollock, David, and Ruth E. Van Reken. 2001. Third Cultured Kids: Growing up Among Worlds. Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Ringheim, Trude. 2000. “Ja, jeg elsker dette landet.” Dagbladet. January 15.

- Skarsgård, Marianne. 2012. “Suksess mot alle odds Loveleen R. Brenna staket ut ny kurs. Slikfant hun veien til suksess.” Hegnar Kvinner. HegnarOnline, April, 17. Accessed 11 July 2017. http://www.hegnar.no/Nyheter/Livsstil/2012/04/Suksess-mot-alle-odds.

- Stoltenberg, Thorvald. 2001. Det handler om mennesker. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Storhaug, Hege, and Human Rights Service. 2003. Feminin integrering: Utfordringer i et fleretnisk samfunn. Oslo: Human Rights Service.

- Sturm-Martin, Imke. 2012. “Migration: Europe’s Absent History.” Eurozine, May. Accessed 11 July 2017. http://www.eurozine.com/migration-europes-absent-history/.

- TrAP. 2017. “10 undersøkelser: Migranten.” Accessed 11 July 2017. http://www.trap.no/prosjekt/10-unders%C3%B8kelser-migranten.

- “Typisk kvinn folk.” 2008. Avisa Nordland. March 8.

- Undset, Sigrid. 1920-22. Kristin Lavransdatter. Kristiania: H. Aschehoug & Co.

- Uri, Helene. 2017. “Hun inviterte Ghandi & Undset.” In Udir: Et magasin for grunnopplæringen med studieseksjon, 6–10. Oslo: Utdanningsdirectorat.

- Wallace, Charles. 2004. “Nice Witch of the North.” Time, August 22. Accessed 11 July 2017. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,685999,00.html.